How Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and Hulk Hogan Threaten Freedom of the Press

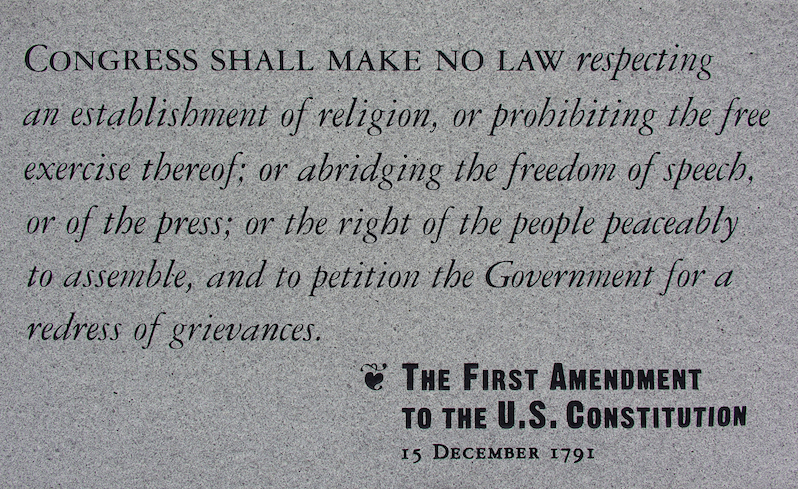

The power elites that rule America are threatening the First Amendment again—and the assault is not coming just from government agencies. The First Amendment is one of the 10 amendments that make up the Bill of Rights. (Ed Uthman / CC BY-SA 2.0)

1

2

3

The First Amendment is one of the 10 amendments that make up the Bill of Rights. (Ed Uthman / CC BY-SA 2.0)

1

2

3

The First Amendment is one of the 10 amendments that make up the Bill of Rights. (Ed Uthman / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.