Hey, Progressive: Who Are You Calling a Neoliberal?

During the 1960s anti-war movement, many leftists and Democratic Party leaders could not find common ground. That’s still true today. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., speaks at an April rally for Omaha Democratic mayoral candidate Heath Mello in Nebraska. Sanders, who attracted millions of college-aged and young adults to his 2016 presidential campaign, is following through on a promise he made when he left the race: to promote younger leaders for the Democratic Party. Charlie Neibergall / AP

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., speaks at an April rally for Omaha Democratic mayoral candidate Heath Mello in Nebraska. Sanders, who attracted millions of college-aged and young adults to his 2016 presidential campaign, is following through on a promise he made when he left the race: to promote younger leaders for the Democratic Party. Charlie Neibergall / AP

I recently wrote a book about the late 1960s, so maybe the reason I don’t like the word “neoliberal” being deployed by some on the left against a wide variety of Democrats of varying views stems from my memory of my mother’s reaction when I first played her Phil Ochs’ song, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal.”

I was a senior in high school in early 1967, a couple of years after Ochs had written the song. My parents were against the Vietnam War, which was the issue that divided Democratic Cold Warriors from those in the anti-war movement. But my mother loved the word “liberal,” which she identified with civil rights, Women Strike For Peace, Eleanor Roosevelt and the New Deal.

When she heard the first verse of the song—in which Ochs’ cartoon liberal says he cried when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot but that Malcolm X “got what was coming”—my mother was pissed. “It’s not fair to say that all liberals are hypocrites,” she complained.

I shrugged off her wounded tone as a symptom of the generation gap. At an anti-war rally in Washington, D.C., Students for a Democratic Society President Carl Oglesby made the distinction between New Deal liberals and pro-war “corporate liberalism.” He knew that some would claim he sounded anti-American: “To these, I say: ‘Don’t blame me for that! Blame those who mouthed my liberal values and broke my American heart.’ ”

By the end of 1967, many in the anti-war movement preferred the word “radical” to indicate antipathy to the avowed liberal President Johnson, who had put 20 million young men at risk of being drafted to kill or be killed in a war many of us felt had no connection to American security interests and was immoral because our government was siding with anti-Democratic tyrants. (Alas, the word “radical” soon was co-opted by some who thought that exploding bombs in “Amerika” would accelerate the end of bombing in Southeast Asia. Hence the subsequent revival of the word “progressive.”)

During the Trump era, feelings are again raw between many on the left and many of the leaders in the Democratic Party.

As someone who publicly supported Bernie Sanders in the primaries, I think the primary burden of creating an effective anti-Trump coalition must come from an outreach to progressives from mainstream Democratic leaders and institutions, but they lost touch with their base on many issues long ago. Such mainstreamers claim that they and they alone are pragmatists, yet these leaders presided over the worst Democratic electoral results since the 1920s. Author and activist Howie Klein often points this out at downwithtyranny.com: The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee persists in supporting corporate-leaning candidates for Congress even in blue districts. This approach is not how to motivate Bernie voters or the full spectrum of the Obama coalition.

At the same time, those of us who supported Bernie have to do our part in minimizing self-destructive internal bitterness, much of which is more tribal than substantive. I recently wrote a piece on this for The Nation, suggesting that the left should stop using the word “neoliberal” as a conversation stopper that lumps in traditional liberals with corporate Dems. That same week, at least five other pieces were published about the word—first by Jonathan Chait in New York magazine, followed by four critical responses to it by Sam Kriss at AlterNet.com, Mike Konczal in Vox, Eve Peyser in Vice and Paul Blest in The Outline.

Chait appears blind to the major issues that have alienated millions of progressives from the Democratic Party. He insists that Democrats have stood for the same values since the 1940s by citing something called the “Poole-Rosenthal chart,” which supposedly calibrates political party moves to the left or right, as if there is a mathematical formula for ideology and policy. This pseudo-science makes it seem that lefties simply imagined that many Democratic leaders in the post-Reagan period departed from the New Deal and Great Society philosophies to embrace a more “pro-business” attitude and attract “Reagan Democrats” and corporate donors.

This is the pundit equivalent of gaslighting the millions of Democrats who embraced Bernie Sanders in the 2016 primaries and embodies the condescending attitude that has fueled rage on the left.

I have never regretted voting for Bill Clinton and Barack Obama because they were better for the 99 percent than the people they ran against and more progressive than the Republican congressional leaders who tormented them. However, I often despaired when they both kept progressives at a distance while conveniently insisting that this was the only way to prevent Republicans from gaining power.

Progressives were asked (or, more often, told) to swallow the fact that Clinton deferred to his secretary of the treasury, Robert Rubin, who spent 26 years at Goldman Sachs prior to joining the administration. In his 1996 State of the Union speech, Clinton asserted, “The era of big government is over,” and soon thereafter dismantled “welfare as we know it.” He presided over NAFTA (against the wishes of the labor movement), the deregulation of the broadcasting business and repeal of the Glass-Steagall law that prohibited several of the banking practices that led to the 2007 financial meltdown. And then there was that expansion of the drug war that accelerated mass incarceration.

Notwithstanding many admirable aspects of his presidency, Obama also resisted what his press secretary, Robert Gibbs, condescendingly called “the professional left.” Obama’s economic team was led by Larry Summers and Timothy Geithner, both acolytes of Rubin and far more supportive of bankers than were most Democratic voters.

Yet the fixation of some on the left with the word “neoliberal” to describe Democratic political adversaries is reminiscent of the right-wing obsession with the phrase “Islamic fundamentalist terrorism.” Neocons insisted that Obama’s avoidance of the phrase somehow encouraged actual terrorism. Stating the fact that it needlessly alienated non-terrorist Muslims was falsely depicted as weakness.

To be clear, a decision to stop calling Democrats one disagrees with “neoliberals” does not require refraining from arguing passionately about issues or periodically mounting primary challenges to Democrats who are out of touch with the progressive base. It just means that name-calling, especially names that implicate many potential allies, is ineffective.

In his song “Revolution,” John Lennon tartly sang to those in the ’60s who claimed they were on the cutting edge of radical social change: “We’d all love to see the plan.” It’s hard to imagine political victories that actually help the 99 percent without at least a temporary coalition on some issues and elections among all branches of the anti-Trump populace.

The epithet “neoliberal” has at times been irrationally used to tar Wall Street-friendly economists such as Rubin and their fierce critics, such as Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman, with the same brush.

A similar lack of discrimination appears in a recent Salon piece about an odious new hawkish think tank in which a couple of relatively unknown Democratic advisers (referred to as neoliberals, of course) are joining neocons like Bill Kristol. This depressing development is presented as evidence that “Democrats” are for new wars, as if hundreds of anti-intervention politicians, such as California Rep. Barbara Lee, weren’t also Democrats.

Amid the infighting have been a few positive signs. Tom Perez defeated Keith Ellison for Democratic National Committee chairman in an ugly election in which Ellison (who was supported by Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren) was unfairly smeared. Unlike most previous Democratic establishment victors, Perez wisely recognized the need to reach out to progressive voters who had supported Ellison, and Ellison agreed to accept the role of DNC vice chairman. The two have made several public appearances to help unify the party.

More substantively, there has been an effective inside/outside coalition regarding heath care. Protesters at congressional town hall meetings were central to illuminating the harm that would be done to millions of people if the Affordable Health Care Act was repealed. At the same time, Senate Democratic leader Charles Schumer unified opposition to repeal the AHCA with a Democratic caucus whose members range ideologically from Sanders to such senators as Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, whose states voted for Trump by double-digit margins. Schumer subsequently said he was “open” to single-payer health care, a breakthrough that was preceded days earlier by Al Gore’s support for single-payer.

In the ’60s, many counterculture leaders were so focused on moving American politics in a more radical direction that they failed to see the threat from the right until Richard Nixon and his minions held the reins of executive power.

Trump, unlike Nixon, has a Republican Congress, a more conservative Supreme Court and a supercharged national security apparatus at his disposal. It will take a supermajority of public support to prevent a lot more dreadful things from happening.

I will always love the music of Phil Ochs. “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” “There but for Fortune,” “Changes,” and “Flower Lady” are among my favorite songs of all time. But in retrospect, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal” wasn’t all that helpful in the ’60s. Neither is the word “neoliberal ” today.

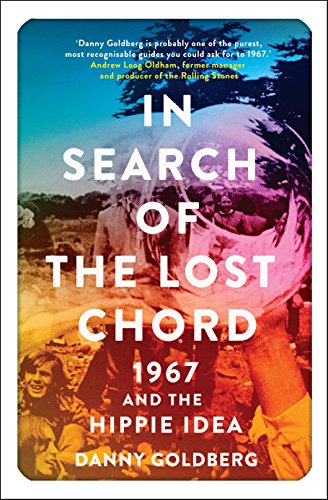

Danny Goldberg is author of the book “In Search Of The Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.