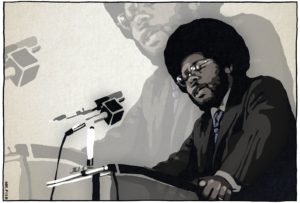

E.J. Dionne Jr.: Christianity’s African-American Soul

A New Testament scholar and ordained Baptist minister's new book suggests that African Americans' interpretation of Scripture best captures the authenic meaning of the Bible.“African-Americans read their own collective experience into the agony and exaltation of Jesus. The story of the Christ child, blessed by God yet born in the shadow of poverty and violence, was their story. Jesus’ humble birth in antiquity signified the humble origins of African peoples in modernity. In his impoverished entry into the world, Jesus turned the tables on earthly valuations. Fulfilling the promise of the oracle that celebrates his advent in a stable, the hills of the privileged and the valleys of the humble are inverted, marking the beginning of a new era.”

— Allen Dwight Callahan in “The Talking Book: African-Americans and the Bible.”

WASHINGTON — Great traditions are subversive. They constantly call the imperfections of the present to account in the name of a more exalted standard.

Abraham Lincoln marshaled the power of the Declaration of Independence to challenge slavery, and every year, the Christmas story overturns our daily understandings of power and privilege. A newborn king and savior appears among us, born to a most unlikely family, in a most unlikely venue, in the least promising of circumstances.

Callahan’s remarkable book, published this year by Yale University Press, describes the rich and intense relationship between the Bible and the African-American imagination. But even more powerfully, it suggests — without making the case directly — that the reading of the Christian tradition offered by African-Americans is as close as any to the authentic meaning of Christianity.

A Harvard-trained New Testament scholar and ordained Baptist minister, Callahan traces the role of “the talking book” (the phrase belongs to Henry Louis Gates Jr., lead editor of “The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature”) from slavery to civil rights and from gospel music to hip-hop. Callahan makes his case in the book’s first sentences: “African-Americans are the children of slavery in America. And the Bible, as no other book, is the book of slavery’s children.”

It is hard, I think, for anyone nurtured in the Christian or Jewish traditions to dispute Callahan’s claim that the Bible “privileges those without privilege and honors those without honor” and that it has a “penchant for bringing peripheral people to the center of history.”

“The God of holy scripture has made slaves no less than their masters in the divine image and likeness,” Callahan writes. “The Apostle Paul had declared that master and slave were equal in God’s sight. And in the book of Exodus, God had freed the ancient Hebrews from bondage in Egypt; the liberation of slaves had been God’s will. These were ideas at least as revolutionary as any Jeffersonian proposition.”

All this might sound odd to members of two groups. Some on the left see religion as an “opiate of the masses” that offers the oppressed “pie in the sky when you die,” in the words of the old song, by way of diverting them from rebellion against this world’s injustices. Many on the right see Christianity demanding allegiance to conservatism, and there are a few who can’t seem to distinguish between the Scriptures and any given year’s Republican Party platform.

Callahan is alive to the fact that the Scriptures and the meaning of Christ’s story have always been contested. Elijah Muhammad of the Black Muslims called the Bible “a Poison Book.” Slave owners emphasized biblical passages calling upon slaves to submit to their masters. “According to the testimony of slaves themselves,” Callahan writes, “obedience was the first commandment of the Christianity preached to them.”

Yet the Bible’s subversive message could not be successfully blocked. Frederick Douglass, the ex-slave and abolitionist giant, spoke of two religions called Christianity, “the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land” and “the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ.” Many years later, W.E.B. DuBois, a founder of the NAACP, called Jesus “the greatest of religious rebels.”

And no story has played as large a role in African-American faith as Exodus. Introducing Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 to a Jewish audience as a modern prophet, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel declared: “The exodus began but is far from having been completed. In fact, it was easier for the children of Israel to cross the Red Sea than for a Negro to cross certain university campuses.”

Callahan cites the words of an old Negro spiritual:

Poor little Jesus boy Made him to be born in a manger. World treated him so mean Treat me mean, too.

The poor, the outcasts, the slaves: If Jesus spoke to anyone, it was to them, and they have responded to him through the centuries. The African-American religious tradition is a blessing to all because it requires us to remember that Jesus of Nazareth really did revolutionize the world.

E.J. Dionne Jr.’s e-mail address is postchat(at symbol)aol.com.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.