Corky Lee and the Work of Seeing

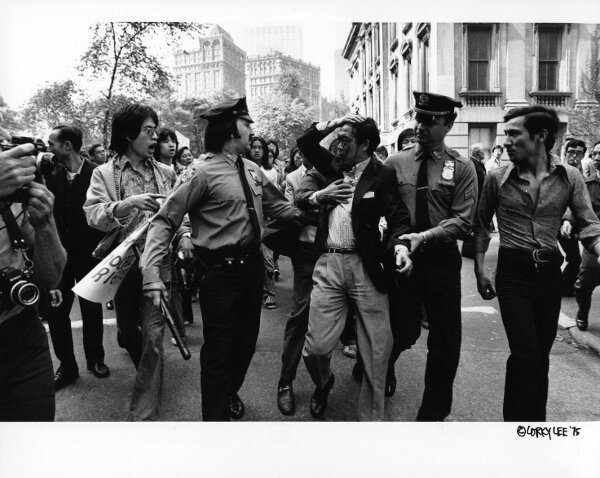

Corky Lee's photographs are portraits of structural forces. Corky Lee, "Peter Yew Rally," 1974.

Corky Lee, "Peter Yew Rally," 1974.

I did not realize that Corky Lee would pass away. I heard early reports that the radical photographer had contracted Covid-19 and stayed overnight at the hospital, but then he began to recover. We weren’t close, but he was so ubiquitous, such a fixture at seemingly every Asian American civic event, that he came to feel more familiar than many of my friends. A secretly shy person, he dodged his introversion by simply taking your photograph, or he’d pounce on you with a harangue, his manner paradoxically imposing and self-effacing. His opening gambit was to school you. He’d catch you up on some esoteric fact about labor history or mention an upcoming open mic with the implication that you should’ve already known about it. His knowledge was not the ideological preciousness encouraged by social media. It was scrappier, a shrewdness of the street. His images captured fifty years of Asian American radicalism, and perhaps because photography preserves a vision of its subjects against erosion, age, and death, I realized that when he passed away on January 27, 2021, I had long assumed that Corky Lee himself would be immune to time.

A decade ago, we met for dinner with his longtime partner Karen Zhou and his friend, the historian Peter Kwong. Like many children of immigrants, I’d come to think of any Asian older than me as somehow more “authentic” and instinctively readied myself for Corky ordering everything in Chinese, just as my father would have done. I was bemused when he began flipping the pages of the menu back and forth and asked me, almost timidly, if I could recommend what to eat.

It was then that I registered Corky’s fundamental temporal incongruity. He was a second-generation Asian born before the borders loosened in 1965, which made us both ABCs: assimilated, educated, clueless. “I’m Asian American,” I recall him saying that night. “So I’m a 100 percent authentic fake.”

I loved the knowing wink of this line, its carefree shrug at racial fronting, ancestry, and supposed tradition—the way it packed a treatise about the social construction of race into a single spat-out wisecrack. Here was a theory of ideology. Rather than searching for a dubious authenticity, essence, or nationalism, Corky suggested that Asian American identity did not possess—and also did not need—any underlying reality beyond solidarity. The Asian American project was an invention, a provocation thought up by small bands of liberals and radicals who came together despite their divergent homelands, ethnicities, and languages. But what also becomes clear when looking at Lee’s photographs is how what it meant to be Asian American then is not what it means now: the historical specificity and limits of an identity designed to be capacious.

The day after Corky Les passed from Covid-19, Vicha Ratanapakdee was tackled in San Francisco and died days later. More street assaults followed. A gunman besieged two Asian massage businesses in Atlanta. Another shot up an Indianapolis warehouse staffed by Sikh migrants. In response, the movement that became known as Stop Anti-Asian Hate began flooding Instagram with snapshots and videos of Asians experiencing brutal aggression. These images arrived pre-interpreted, their meanings already determined. Rather than an unstable mix of racial outsiders and economic elites, Asian Americans could now be seen as victims within a liberal milieu that bestows racial recognition in return for trauma. There came a new ontology of dread, anxiety and attackability.

I found the videos disturbing. I resented the expectation that I should be afraid. I detested their necromantic vibe and moral panic, which reminded me of channel-surfing past America’s Most Wanted as a teenager. I had spent more than a decade running an Asian American community group—a nonprofit that elicited a rapturous sense of recognition from Asian Americans and perplexed indifference from others—so the idea that non-Asians should care about us struck me as novel, even unnerving.

One night while doing the dishes I watched a slideshow Lee had presented at CUNY, felicitously preserved on YouTube. In one of the photos, a woman holds up a sign that reads “Hate crime is another terror.” Her friend holds the same sign in Hangul. A premonition—and also a challenge: what did the history catalogued in Lee’s archive have to tell us about “Stop Anti-Asian Hate,” whose advocates sometimes seemed unaware of the past two decades of Islamophobia or other flashpoints of Asian American history? As the photos flickered by and the cheesy musical score rose to a crescendo, I felt like I was seeing the last episode of some beloved TV show, a clip show featuring everyone’s favorite memories from seasons past—the series finale of the Asian American Movement! I watched tributes to Lee organized by La MaMa Experimental Theater and the Asian American Arts Alliance. Both featured speeches by his old comrades: fierce, funny, mournful people, many of them in their eighties and nineties and possibly teetering on extinction, forgetful and often perplexed by how to operate Zoom.

There is a symmetry between Corky Lee’s passing and the rise of Stop Anti-Asian Hate: the departure of Asian America’s greatest documentarian and its most visible recent efflorescence. Years earlier, the brief window of postwar Asian American radicalism seemed to have already swung shut. Today, our most notable figures are corporate CEOs and conservative politicians, the eponymous Asians rich and crazy, so the artists, revolutionaries, and workers preserved in Lee’s prints can feel as elusive as their author. No matter how distant an Asian American poor people’s movement may seem, his prints still vibrate with radical temporality and potential. They are photographs of a speculative past. They whisper toward what an Asian American politics could become. In 1971, Corky caught the radical intellectual Grace Lee Boggs in the process of discovering a statement. She has begun writing, “Asian Lives are . . .” but for a suspended moment, the sentence has not concluded. Asian American politics remains a possibility.

Grace Lee Boggs’s placard might eventually say “Asian Lives are not disposable,” a slogan that wouldn’t be out of place at a Stop Anti-Asian Hate rally. But who would she mean by “Asian”? Neither Boggs, nor Yuri Kochiyama, the other most famous Asian American radical, really thought of themselves as “Asian American.” I wondered what would happen if we talked about Corky Lee’s photographs and Anti-Asian Hate without acting as if either could be causally explained by that phrase. I ask this question not out of skepticism, but from a fierce loyalty to the original politics of the Asian American project. Lee took this photograph at an antiwar rally in Washington DC, so the “Asian Lives” mentioned in the sign probably referred to Vietnamese peasants. In other words, what it meant to be Asian American to them is not what it means to us.

In our moment, the left sometimes seems trapped between a dichotomy between class versus identity, economism versus politics, but Lee and Boggs would not have seen these as opposed. The photograph preserves Boggs and Lee at a protest against the Vietnam War, only the latest in a series of brutal American wars across the Pacific. The Japanese American concentration camps were still a fresh memory. The children of rural Toisanese migrants, Lee and Boggs represented a college-educated second generation in a time when Asian Americans labored in sweatshops and factory farms. Both were radicalized by the politics of affordable housing: Boggs by the poor living conditions endured by Black residents in Chicago, Lee by the Chinatown tenements that crammed several migrants to a room. For Lee and Boggs, the struggle centered on war and the nexus of underpaid labor and substandard housing, all issues central to the nature of Anti-Asian Hate, but ultimately elided by its monolithic focus.

In the photograph, the child stands less than a foot away from a woman focused on her sewing. Is she the mother?

Originally an outsider from Queens, Lee emerged into a Manhattan Chinatown drawing in new migrants after 1965. Many who came were something new and anomalous: Chinese women, a rarity in the bachelor societies that previously comprised the Asian diaspora. Lee’s father had migrated to America and become a veteran, then a welder, before opening the family laundromat. Lee’s mother was a seamstress. As a child, Lee washed clothes alongside his three brothers. And so when I saw this 1976 photograph he took at an Elizabeth Street garment factory, I wondered if he was reminded of home.

A whole dreamy world seems contained in the cocked head of the child. What is she holding? What is she thinking? She becomes the bright center of a photograph overwhelmed by pure material, the massive heaps obstructing the view of even the grownups, the foreground of commodities and textiles like Capital’s abstract math problems restored to their original phenomenological form. We can compare Lee’s image to another garment factory photo by Budd Glick. In Glick’s composition, you can better identify the figures, who aren’t cropped or obscured as they often are in Lee’s photographs; in this one, the industrial setting overwhelms the tropes of portraiture. Glick frames the overheard fluorescent bars like luminous lines from a Jacques Tati film, the lighting crisp and delicate. His photo shows Chinese people working in a factory. In Lee’s image, you notice something else. You notice the drawing of a woman’s face over a door—is this the women’s restroom? You notice the child, who may be simultaneously a sweatshop worker and a little one who must be taken care of. In this workshop of migrant women, the world of work and the world of mothering becomes one.

To be a worker may be a universal condition, but capitalism also differentiates workers, often preying on poor migrant women like the one we see above. The woman in this photograph was probably paid by the piece, not by a wage, and imagined as a contractor, not as an “employee”; the child’s presence also suggests a blurring between labor and the housework of childcare—did this mean she was not a worker? You might assume the child was not a worker, but we know that many children did work in Chinatown factories. Both the woman and the child existed between the proletariat and the lumpenproletariat, the worker and the degraded nonworker. Naming the unemployed, the invisible, and dispossessed, the lumpenproletariat could plausibly describe the ensemble of midcentury Chinatown types: the gangster, the sex worker, the gambler hustling to make ends meet, the urchin, the elderly busker fiddling his erhu, the grandmother gleaning for cans and tossing them into her planet-sized sack. Lee’s photographs depict those living in the unstable flux between work and nonwork, the vertiginous rung occupied by the poor ethnic laborer who wants a productive role in a society that sees them as an outcast.

In the photograph, the child stands less than a foot away from a woman focused on her sewing. Is she the mother? We have no way of knowing. We tend to imagine industrial workers in America as white men, but this photograph shows otherwise. In Chinatown, the men worked as sorters and pressers, which paid better. The women operated sewing machines, the less fortunate stuck with trimmings or left to wrangle the “pork neckbones,” as they called the hard-to-sew pieces. You cannot quite see the woman’s expression in the photo. Her face is hidden by the work.

Corky Lee’s images do something we do not usually imagine photographs can do. Rather than merely showing the visible, they are portraits of structural forces.

The women on Elizabeth Street probably joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, which fought for a union contract in the early 1980s. She may have marched alongside twenty thousand other seamstresses on June 24, 1982, when the union tore through Chinatown and paraded into Columbus Park, where they riled up the crowd with bilingual speeches and raucous Cantonese slang. Of course, Corky Lee photographed that too. In the factory image, women are obscured behind thickets of raw material, but in his depiction of the rally, so many women stand together that they overwhelm the eye. Each wears a white cap identifying her local. The caps float like sails above the ocean of their faces, angular as the white signs and the white horizon erected by their banners. Endless polygons of negative space: the print looks like it was carved out with a knife.

In one manner of speaking, the seamstresses won. Conducted a year after Reagan fired the striking air traffic controllers, their strike was the largest in Chinatown history and one of largest American strikes that decade. Most employers caved and signed their contract, which would eventually create a union-organized daycare that presumably benefitted children like the one we glimpsed in the Elizabeth Street factory. While Lee’s infinite archive can convey a sense that he is an omniscient narrator, his practice possessed an enormous temporal breadth and a deep but limited spatial range. He spent half a century documenting an Asian American politics often circumscribed by Manhattan’s Chinatown. These two photographs take place within blocks of each other.

Corky Lee’s images do something we do not usually imagine photographs can do. Rather than merely showing the visible, they are portraits of structural forces. A photographer’s work is bound by where they are and who they know. They create rubbings of the corporeal. While these women worked in garment factories, so too did other women, perhaps even their relatives, on the other side of the world. I found myself imagining an all-seeing viewer peeling off the cropped edge around this photograph and expanding the frame of the image until we could see these women’s doppelgangers working in garment factories in East Asia. Lee was only a single person. His photographs cannot be infinite. They cannot show the other side of the arc of diaspora, the labors of those who did not leave, but the seamstresses, like Lee and his father, were all shaped by forces on the other side of the planet.

When America fought Japan in World War II, there was a more domestic side effect. The war jumpstarted the US’s industrial economy and created mass employment. The military employed Lee’s father and Lee himself served as a draft officer during the Vietnam War. The role makes more sense when one learns that he encouraged his draftees to conscientiously object, according to one of his conscripts, Tzi Ma, the actor who would go on to play seemingly every Asian Dad in Hollywood. If World War II created an upswelling in domestic manufacturing, the Pacific wars would ultimately produce the opposite effect. America relocated its factories first to Japan, then to occupied Korea, and Taiwan, which built armaments and heavy industry for the war in Vietnam. In other words, the East Asian economic miracle, as Jim Glassman writes, originated from the very Southeast Asia massacres that we glimpsed Grace Lee Boggs protesting. Factory jobs began fleeing the United States, but Lee photographed one counterintuitive exception: New York City.

The women marched into Columbus Park to fight the attempt by manufacturers, union president Sol Chaikin said, “to create a Taiwan in the United States and turn the union clock back fifty years.” In other words, the seamstresses wanted to preserve workers’ rights that the American occupation had already crushed in East Asia. Manhattan Chinatown became the largest Chinese neighborhood in the US during the ’70s and ’80s: a thriving archaism, an ethnic factory town in a country moving its factories abroad. Manhattan, now hardly anyone’s idea of a manufacturing center, staved off deindustrialization thanks to the combination of migrant labor and, as Lena Sze has argued, housing stock whose squalid conditions meant they were cheap—an inadvertent, illicit affordable housing.

Corky Lee started out as an organizer at Two Bridges Neighborhood Council. He convinced tenants to collectively withhold rent until their landlords made repairs and ameliorated their abysmal living conditions. The apartments in Chinatown often lacked heating, hot water, and plumbing and packed several people into a tiny, dingy room. Of course, these inhumane conditions meant that even poor migrants could afford them. To persuade the tenants to organize, Lee showed them photographs he’d taken in other buildings, displaying the original state of neglect and the improved conditions brought by collective pressure—a little like, he later joked, the before-and-after photos in a weight-loss commercial. At first, he did not even own a camera and had to borrow his roommate’s Pentax.

The memory of Chin’s death reemerged in our new age of Anti-Asian Hate, but that moment differs from our own.

This is how he discovered photography: as a tool in his own self-described work as a propagandist. Lee understood photography as a way to record the material conditions of tenements, not as an expression of anything he felt or dreamed. As a proletarian artist, Lee condensed the arc of 20th-century radicalism into the splintering alleyways near Mott Street, but this did not mean his work was forceful, imposing, or didactic—some of the affects we tend to associate with agitprop. We might better describe proletarian art as delinquently authored, created by anti-authors unwilling to hang their craft in some autonomous zone floating beyond society. Lee captured a blue-collar Chinatown whose factories reproduced the labor militancy of the Old Left and the identity-based movements of the New. Because he often shot in black and white, even his recent photos look like they have emerged from an already historical moment, a tactile world of developing fluid, chemical film, and print culture. But Lee claimed he’d been blacklisted by the Associated Press. He’d asked the daytime photo editor there to print a photograph of activists protesting a perfume called Opium. When the editor turned him down, Lee went around him and got the night editor to print it, earning the eternal ire of the former. Escaping the more mainstream economies of newspapers, he went to work as a printer at Expedi, a pan-Asian press whose clients included ethnic media like India Abroad and Asian Week (both now defunct) and downtown arts fixtures like the Poetry Project and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop—and was laid off when that world of newsprint collapsed. When Lee was alive, you could probably only have seen his prints in some community basement a few blocks from where they’d been taken. Geography was vital. In the early years, Lee launched a Chinatown health fair (the future Charles B. Wang Health Center), coined the name of the new community’s arts hub, Basement Workshop, and co-founded the Asian American Arts Alliance, the Asian American Film Festival, and the Asian American Journalists Association. Having created many institutions, he ran none of them. He could slip between the fertile new groups sprouting up across town and document them all.

What this means is that every person in most of Lee’s photographs—as well as in the organizations he helped found—is Asian American. His images do not depict diversity, since they do not show an Asian American as a minority within a larger white tableau. Representation can be a form of translation, containment—and stereotypes are tools to explain the represented person and render them legible. The paradigmatic literary genre for ethnic self-representation is the memoir, which expects writers to curate their own racialization for others. Many forms of racial representation imply that an exemplary figure—say, a politician, celebrity, or author—can stand in for a broader ethnic public that won’t be included itself. Lee did the opposite. He took few self-portraits and photographed everyone else. For every Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama, as poet Taiyo Na put it, “he also took a photo of you.” Simply by being there, Corky’s appearance said you mattered, which is why his death unleashed an astonishing democracy of grief.

Rather than displaying a painterly composition, Lee’s work might be better understood as a durational practice. The nature of his work involved observation, gossip, hooking people up. If you look at a “beautiful” photograph today, it will have a shallow depth of field and a blurry background, thanks to iPhone portrait mode and television trying to look “cinematic.” Lee instead used a wide-angled lens so he could more fully capture the mise-en-scène that we call social reality. His images lack a charismatic subject. Those whom capital dismissed as surplus, he saw as beautiful. He commemorated the multitude, the striking waiters and seamstresses whose unruly abundance crowded away any beatific composition. He was the social “glue,” writer Amy Chu said at one tribute I watched, but also an “enigma.” An artist of relationships, Lee was the audience, the public, someone who observed aggressively—the one person not in the photograph.

On June 23, 1982, the day before the seamstresses marched, a man named Vincent Chin was murdered by two aggrieved white men. Chin’s death inaugurated a campaign for his killers to be held accountable. Though the seamstress strike involved thousands more people, those were poor women in an ethnic ghetto. It is the crusade for Vincent Chin that people remember as catalyzing the next Asian American movement. Compare Lee’s photo of a Vincent Chin rally in Detroit to the earlier one of the seamstresses. The Detroit protesters don suits and carry American flags. Their signs are a plea for someone to grant them recognition from the outside. The garment workers announce the power they have created themselves.

Those women were economically positioned to threaten their employers, while many of Chin’s advocates were lawyers and reporters who worked outside the industrial nexus of Detroit. Their only leverage came from the legal system and the media, prefiguring our current moment of representational politics. In the prior photo, the seamstresses do not pose towards an outside viewer. In this Detroit photograph, the protesters march forward as if on a proscenium stage. Their strategy relied upon a different audience, one whose powers of broadcast and memory canonized the movement for Vincent Chin: the camera.

You can easily glimpse the class difference between the garment workers and the Detroit protesters, but what are the clues that tell you this? It is their fashion: neckties, suits, and sweater vests, wide lapels, flared pants, and sunglasses. Who knows if any of their clothes had been patterned, cut, and sewn by seamstresses in Chinatown? While the garment factories persisted in Chinatown, exploiting undocumented workers who lived in the tenements, Detroit had experienced a boom from wartime industry only to find itself competing with the very manufacturers the US occupation fostered in Japan. The city decayed as the big auto companies left Detroit. In Lee’s photograph, more than one sign reads, “A job is a license to kill?” This is a reference to how one of the killers, a man named Ronald Ebens, had yelled at Chin, “It’s because of you little motherfuckers that we’re out of work.” Ebens seemingly declared his motive, and Chin’s murder is often understood as caused by resentful white men crazed by unemployment.

This narrative is slightly incorrect. Ebens, the man who actually killed Chin, worked as a Chrysler superintendent. His stepson Michael Nitz, who held Chin while Ebens struck him, was laid off by Chrysler but found other work. Judge Kaufman defended his lenient sentencing of Ebens by saying, “We’re talking here about a man who’s held down a responsible job with the same company for 17 or 18 years . . .” In other words, the answer to the protester’s sign was a barbaric affirmative. What rendered Ebens innocent was not whether he committed the crime, but his employment. He only lost his job when Chrysler fired him for the murder.

Neither Ebens nor Nitz were found guilty in the civil case, a hint at the limits of trying to put killers behind bars. Even though they both pled guilty in the criminal lawsuit, they suffered only probation and a $3,000 fine, which Ebens never paid, instead relocating to Las Vegas. The photograph contains four American flags, a recurring and sometimes troubling motif in Lee’s photos. One of them is not carried by a protester. It is part of the public square, a symptom of the landscape. Detroit autoworkers, who spent the prior decade in a state of insurgency, held rallies where they bashed Japanese cars with sledgehammers. Organized labor’s vulnerability to racial division had already been diagnosed by the Black Power theorist James Boggs, who I came to realize had actually overlapped with Ronald Ebens as an employee at Chrysler in the ’60s, though they probably worked at different factories. As Detroit collapsed, Scott Kurashige writes, the auto companies fled the urban core, a stronghold of labor and Black militancy, and set up in the suburbs, which were ununionized, mostly white, and the home of both Chin and Ebens. Left behind were the Black workers, many of whom were now unemployed. James Boggs wondered if the revolutionary subject were not the proletariat, as Marx had predicted, but the lumpenproletariat, those who had been segregated from capitalism. Shortly before he died, Corky Lee said his next project might involve shooting mourners outside Ebens’s home—a hint at how his own practice would turn towards fantastic performances of memory. He wanted to recover Vincent Chin, who had dwindled into a half-forgotten martyr.

The memory of Chin’s death reemerged in our new age of Anti-Asian Hate, but that moment differs from our own. Today’s aggressors are utterly different, as are the victims. The man who killed Vincent Chin was a wage laborer in a segregated industry town. Most assailants perpetrating violence against Asian Americans, whether in San Francisco or New York, were homeless. They are the lumpenproletariat ostracized from society. As the homeless population exploded in recent years, a spike in violence against the homeless accompanied it. Many elderly Asians, like the seamstresses and tenement dwellers, come from the pre-1965 class divide. What distinguishes them is not just their race, but their poverty and housing instability. Think of Yao Pan Ma, who lost her job as a home health care attendant and was collecting bottles and cans when she was murdered. A highly circulated video showed a Chinese grandmother named Xiao Zhen Xie defending herself against an attacker. A subsequent, less publicized video captured a different narrative. Her assailant was a homeless man had been battered by aggressors of his own. Fighting back in a daze, the man swung clumsily at Xiao. Their meeting was a tragic spatial coincidence. The video’s terrible complexity comes in capturing how anti-Asian violence intersects with that meted against the homeless themselves.

In San Francisco, video footage caught a terrified Asian senior facing jeers and intimidation: he too was a homeless man who gathered discarded bottles. Not far away, a great-grandmother named Yik Oi Huang died from a beating delivered in a playground. These two incidents happened before Covid’s arrival, suggesting causes other than pandemic racism. Like Detroit, the Bay Area flourished thanks to wartime factories. The area’s manufacturing history is preserved in the mountains near the 101 North where large white letters shout out SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO THE INDUSTRIAL CITY, the signage floating like subtitles for the sky. While Detroit collapsed into ruins, San Francisco transformed into investment property, one of many factors contributing to its homelessness crisis. The attacks against the homeless bottle-collector and Yik Oi Huang happened in the Visitacion Valley and Bayview neighborhoods, where redlining pushed the Black community fighting to stay in the city.

Rather unusually, Corky Lee was the New York–based documentarian of a movement typically associated with California. He does not seem to have photographed its most famous defeat: the expulsion of elderly Filipino men from San Francisco’s International Hotel. This eviction was a counterintuitive but maybe more illuminating precursor to our moment of anti-homeless violence. Lee’s work often showed Asian Americans coming together to defend themselves against sudden eruptions of violence, as we saw in Detroit. I think of these moments as ascription crises, flashpoints where one’s racialization becomes abruptly redefined by external violence. To paraphrase Eric Williams, these attacks did not necessarily happen because of race. Rather, they create race. It is in these moments that “Asian American identity” is invented.

This new sense of being “Asian American” enveloped both the largely impoverished victims and the often more middle-class Asians who watched the violence play out on social media. During the onset of Anti-Asian Hate, progressives blamed the attacks on white supremacy and traced the violence back to the burgeoning cold war against China, thanks to Trump’s references to Covid-19 as the “China virus” and “kung flu.” But what, as conservatives inevitably asked, did it mean that some attackers were people of color? Or that they didn’t always seem ostentatiously racially motivated? This was not quite true. Some attacks were terrifying performances of xenophobia. Jose Gomez III stabbed a man and his son at a Texas Sam’s Club while screaming “Get out of America!” In New York, Tammel Esco called a woman an “Asian bitch” and punched her 125 times. In Bloomington, Indiana, a woman named Billie Davis stabbed a teenager for “being Chinese,” saying “it would be one less person to blow up our country.” But these last two incidences happened long after the idea of “Anti-Asian Hate” was first articulated, and the men who threatened Vicha Ratanapakdee, Xiao Zhen Xie and many of the other victims we saw in viral videos did not announce their prejudices. What did it mean if, in the early days of the attacks, as Esther Wang writes, many Asian Americans “began referring to any attack on an Asian person as a hate crime”? While the origins and motivations of terrible acts can sometimes be unknowable, perhaps we can resolve these contradictions if we identify “Anti-Asian hate” as a highly situated uptick in violence among the poorest of the poor, a conflict that happened to overlap with Trump-inspired prejudice against all classes of Asian Americans. This latter phenomenon was different: only a tiny fraction of the incidences documented by Stop AAPI Hate involved physical conflict.

While we’ve understood these attacks through the binary of racist attacker against Asian victim, another useful prism might be that of property owner versus the unhoused. Much of the footage of Asians under assault, as Jane Hu has written, was not taken by humans. Instead, it came from CCTV and surveillance cameras, photographic sentries installed to protect real estate. In New York, during the George Floyd protests, Chinese conservatives organized rallies in Flushing to proclaim their support of the NYPD and demand the defense of their property and shops. “Unlike the white/fascist pro-police marches that we’ve seen throughout the country,” writes organizer Kate Zen of Red Canary Song, “Chinese immigrants genuinely feel like they are the victim of criminal activity.” But City councilmember Peter Koo put it more baldly when he said, “Business Lives Matter.” In California, Chinese Americans spearheaded a right-wing campaign that successfully recalled abolitionist district attorney Chesa Boudin. If you actually listen to what the recall supporters said, you will see that many complained less about any direct encounters with violent crime than about an unease related to the presence of the homeless.

This movement of Chinese American conservatives actually originated in a debate on policing. From 2015 to 2016, right-wing Asians organized rallies in over fifteen cities nationwide to defend Peter Liang, the NYPD officer who shot and killed a Black man named Akai Gurley. Liang had been conducting a vertical patrol in the public housing complex where Gurley lived. The shooting occurred in a stairwell that lacked proper lighting. When Liang was arraigned and convicted, Chinese conservatives cast him as a modern-day Vincent Chin. This obscene equation was rejected by Chin’s own family, but previously stable iconography like Chin now floated unanchored from their moorings.

This was also true of the attack videos. When they first began circulating during the early days of Covid-19, friends told me they watched them but didn’t know what was actually “real.” Were they actually motivated by prejudice? Or did they depict tragic but fundamentally unrelated moments of brutality? We hadn’t gone outside much during the lockdown. All we possessed was mediation. Unlike Corky Lee’s photographs, the viral videos levitated away from any context, their seductions arising from the apparent obviousness of what they showed. One of the very first videos to catalyze Stop Anti-Asian Hate showed a man named Gilbert Diaz attacked in the streets of Oakland. Diaz turned out not to be Asian, but Latino, as did another miscategorized victim in a Brooklyn subway video that went viral. I knew many Asian Americans irate about a video showing an elderly Filipina woman named Vilma Kari being set upon by a homeless man, while bystanders did nothing to help. In the rush to publicize Anti-Asian Hate, news outlets shared Kari’s name and her video without her permission. A subsequent video, one that did not go viral, told a different story. The bystanders had not seen the man attack Kari. When they found out, they immediately called for assistance.

Last year, a man threw Michelle Go into a subway. There came also horrific attacks against Christina Yuna Lee, GuiYing Ma, Yao Pan Ma, and an elderly woman in Yonkers, all suggesting the attacks were gendered. In April 2021, President Biden signed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, a bill to build collaborations between Asian communities and police; the bill passed with the vote of nearly every Republican senator. In New York, Asian voters in Queens supported the successful mayoral candidacy of Eric Adams, the former NYPD officer who responded to Go’s death by flooding the subways with cops and tearing down homeless encampments, which suggested the police’s primary role as a force to discipline the exploding population of the poor. More attacks happened, but the narrative of Stop Anti-Asian Hate seemed to lose its coherent center, shortly after mayoral candidate Andrew Yang said that Asians had the right to walk the streets without fear of mentally ill people, a declaration that made the power dynamic seem suddenly less simple.

Over the summer, shootings took place at a Korean hair salon in Dallas and a Taiwanese church in Orange County, then in August, a man killed four Muslim men from Albuquerque’s Pakistani/Afghan community. In Dallas, the suspect had been fired for insulting his Asian boss and complained to his girlfriend of being pursued by an Asian mob. But the other two shooters came from the same communities as their victims.

In New Mexico, the suspect was a Muslim man who claimed he served in the special forces in Afghanistan against the Taliban. After being resettled in America, he’d been arrested several times for domestic violence. Was this a case of imperial violence undergoing transference into the family space? The Taiwanese church shooting also emerged from a history of war. The father of the shooter, David Wenwei Chou, had been a soldier fleeing the Chinese civil war and Chou grew up in military housing. A Taiwanese-born opponent of Taiwanese independence, Chou wrote a hysterical seven-volume screed whose title gives a sense of how he saw himself: “Diary of the Independence-Slaying Angel.” He targeted the Presbyterian church because of its strong commitment to Taiwanese sovereignty. In other words, what motivated him was not some anti-Asian animus, but Chinese settler grievance.

We can trace the causes of these shootings toward many origins—whether they be right-wing ideology, mental illness, class resentment, or the brutality of broken men—but these explanations will be less useful if we do not identify the structural forces that lead men to become unmoored from their relationships with other people. Chou had once owned an apartment complex. Tenants described him as a considerate landlord, but in 2012, he endured a near-fatal beating. The police investigated the incident and, he claimed, robbed him. He verbally abused his wife, who divorced him shortly before the pandemic and moved to Taiwan, a process that triggered the sale of the apartment complex. Finding it impossible to hold down a job as a freelance security guard, Chou was evicted from the very property he once managed. He too was homeless, another lumpen exile.

If many of the prior Asian victims had become transfigured into saintly victims, surrounded by our own projections of filial guilt, what shocked me about the church shooting was the cruelty and madness of this 68-year-old Taiwanese immigrant, who in some ways resembled the very Asian elders we were supposed to protect. He would not be the only one. As this essay was going to press, there was another shooting. On January 21, 2023, a man shot and killed eleven people at a family-run dance studio in Monterey Park in Chinese east LA. It was the night before Lunar New Year. When the man opened fire, the dancers initially thought they heard fireworks. I was shocked to learn about yet another gruesome act of anti-Asian violence, only to discover that the gunman was himself an elderly Chinese man. One witness said the shooter, Huu Can Tran, was looking for his wife. A friend of the dance hall owners denied the attack was a hate crime and said the shooting arose from jealousy: his wife had been invited to the dance, but he had not. Later news reports said Tran was divorced. A rug cleaner who lived in a trailer park, he was profoundly alone, like many shooters, and had just told the police that his family was poisoning him. While these last two incidences point towards the misogynistic essence of gun violence, this seemed less true of a shooting that happened just two days later. Another elderly Asian man opened fire on two farms in Half Moon Bay, California, where my father often took me for delicious seafood meals. The shooter, Chunli Zhao, was himself a farm worker. Right now, we know very little about him. The history of violence is complex. There is never one cause.

During the brutal summer of public shootings, I scrolled through Instagram and saw a video of hundreds of people lining up in Chinatown, mostly young Asian women. The queue ends on Mott Street, curls west on Mosco, then north up Mulberry toward Yu & Me Books, which sits across Columbus Park where the seamstresses had declared their power decades earlier. The bookstore was giving out free pepper spray.

From the video, you could feel the tense smog of fear floating above the city and also something else, the hope that comes through self-organization. You sensed that a real person had taken the video, not an automated surveillance camera, probably a concerned volunteer who knew the specificity of these streets. I thought of Corky Lee’s photographs of the same alleyways, how if you were in his photographs, the two of you stood together and for the few seconds when he pointed his camera at you, he cared about you. And inevitably I thought of Lee’s most consequential image, a photograph of Asian Americans protesting police brutality.

On December 3, 1974, two cops stalked some Chinatown youths into the Jade Chalet restaurant on Worth Street. One of them fired. The bullet struck Tsu Yi Wu, a bystander who died simply because he was there. Another altercation happened on April 26, 1975. That Saturday afternoon, a white driver hit another car double-parked on Bayard Street. After an angry shouting match, the white driver slipped through, only to brush against several Chinatown pedestrians. Infuriated, the crowd followed the driver, who turned left onto Elizabeth Street toward the Fifth Precinct police station. The police stepped out. They forced back the crowd and knocked down a teenager.

“Don’t push like that,” someone in the crowd yelled. His name was Peter Yew, a 27-year-old who’d been visiting friends in the neighborhood. The police dragged him inside, where they stripped him and beat him, wounding his forehead and spraining his wrist. Like the cops who shot Tsu Yi Wu, they were not held accountable. Yew was charged with felonious assault. From the point of view of the police, Chinatown had too many roaming Chinese men, whom they interpreted as criminals. Migrants poured into the city, but the housing stock and schools hadn’t kept up. Nor were there jobs. Excluded from government construction jobs, Chinatown workers protested by holding signs that said, ASIANS BUILT THE RAILROADS / WHY NOT CONFUCIUS PLAZA? The police patrolled the streets with an aggressive stop-and-frisk policy. Yew wasn’t a recalcitrant teenager, but a mechanical engineering student. His beating pointed to the indiscriminate nature of police violence, the ways it could reach even the educated middle class. On the day before his hearing on May 12, five thousand activists turned out for a protest organized by Asian Americans for Equal Employment, which connected police brutality to the cuts in social services and discrimination against Asians looking for city jobs. Protesters pelted eggs at the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, which hadn’t supported the march.

They too joined in when Chinatown rallied a week later. This time, shopkeepers closed their doors, deciding that an occupying force was bad for business. Many marchers were women whose placards identified their shop floors. Others carried signs that said, END ALL OPPRESSION and JOBS FOR ALL—NOT WELFARE. In one of Lee’s photos from that day, the march is a river of wide lapels and floral shirts, denim jackets and Asian perms. A city correctional bus carrying prisoners, many of them Black, drove through the march, according to the socialist newspaper The Militant; the prisoners banged and shouted in solidarity. The unlikely coalition between merchants and militants brought out twenty thousand marchers, an astonishing number that nevertheless obscures the movement’s underlying fissures.

The march led to City Hall, where the Deputy Mayor and Police Commissioner met with Chinese leadership. The meeting excluded the more radical youth, who split away from their elders and started blocking traffic on Broadway. The NYPD called for reinforcements. Four hundred officers rolled out. They clashed with the protesters, who gave as good as they got. Four protesters landed at Beekman Downtown Hospital, but so did eleven cops. Lee spotted a man who’d just been struck by a cop just six feet away from him.

He sprinted around the two men—like a linebacker, as he later would later describe it—and crept in front of them, where he could snap a clean shot. The photo reads like a baroque frieze of gestures, bustling with horizontal action. Lee may have dodged the print in the darkroom, since the background looks faded, as if history is already in the process of being forgotten. Follow the eye-lines of the protesters and the police, all of which track towards the wounded activist. He is the one being restrained, not the officer carrying a club. Two cops flank him and they are themselves bracketed by another pair: an agitated Asian protester who literally holds a sign protesting police brutality and a surly white man. The nucleic center of attention, the protester looks like he has one too many hands. Someone else’s grip presses against his heart. He clutches his wound. He pushes his head down, as if to keep his crown from ejecting from pure rage. Staring furiously, wounded like a martyr in Caravaggio, he looks unwilling to be a victim.

After he snapped the photo, Lee sprinted from City Hall through Chinatown toward the New York Post, which printed it on the front page of its afternoon edition. By capturing the assault, Lee did more than interpret the world—he changed it. One of the most circulated images of Asian American radicalism up to that time, the photograph showed the rude abandon of the police, their militarized tenure in Chinatown. Within a week after the second protest, the head of the Fifth Precinct was removed. In July, charges against Yew were dropped and a grand jury indicted the two officers who struck him.

What I love about the picture of the wounded protester is how confusing it is to look at now. We live in a moment where the foremost Asian American politician, Andrew Yang, pushed for police protection. So too do we imagine Asian seniors into perfect victims and conservatives who must be educated out of anti-Blackness by their sophisticated liberal children. These assumptions evaporate when we glance at another Corky Lee photograph.

Both women emanate a sense of their own power and individuality. The elderly woman, stout-faced, powerful, surveys the scene, her hands clasped around a placard that says, in Chinese, DOWN WITH RACIST OPPRESSION / JUSTICE FOR PETER YEW NOW / UNITE AND FIGHT TO VICTORY. Her younger companion stands with lapels wide, her glance angled and her leg cocked out, a posture I associate for some reason with the ’70s. Her sign says, in English, MINORITIES UNITE! FIGHT FOR DEMOCRATIC RIGHTS!

Both of their signs advocate unity, but such solidarity would not last. In 1995, the NYPD killed a 16-year-old named Yong Xin Huang. The grand jury failed to indict the officer, even though he shoved the boy face first into a glass pane and shot him in the back of the head. This time, only forty people came to the courthouse vigil. Unlike Lee’s usual landscapes of packed crowds, this photograph strikes you with its emptiness. The masses from the Yew protests have vanished. In their place is a cardboard shrine, some sidewalk detritus, and a cop staring you in the eye.

Where did that power go? The Chinese community had splintered into myriad ethnic fragments. Undocumented newcomers avoided protests. And the factories fled to the non-unionized hinterlands of Brooklyn, where Yong was shot. I was fascinated by a photograph Lee took of someone who worked in a context outside the unions that supported the Peter Yew protests. In the next image, a migrant mother of seven, Lily Cheung-Lai Chow, hunches forward in her Checker cab, cradling a cup of coffee.

“Some people think it’s awful for a Chinese lady to drive a cab,” she said in the oral history collection With Silk Wings. “They think ladies should stay home and take care of the kids.” Or work at a garment factory. I wondered who watched Chow’s children while she drove. They probably worked at the family Chinese restaurant, where Chow went after she finished driving, threw on an apron, and worked until 11 at night. Once, when a passenger didn’t pay, she chased him into his apartment and proclaimed, “I don’t need a knife. I don’t need a gun. I know gung-fu, so don’t let me see you again.”

You can see the reflections of the city curving in her window, a mirage of tenements and hidden sweatshops where other people worked. Chow glides past them. The picture is a dream of mobility, the chunky cab an armored exoskeleton. Chow was an anomaly, the first Asian American woman to drive this otherwise masculine vehicle, but this role prefigures the degradation of organized labor. In the picture, her small figure is boxed in by the driver’s side window, a frame and also a boundary. She is alone.

Returning to the photograph shortly after the shootings at the Atlanta spas, I noticed something looming above Ms. Chow. Perched above her shoulder like an evil angel, Uncle Sam levels his axe toward Lily Chow’s head. GET IT DONE! AMERICA—what exactly was advertised by this grammatically idiosyncratic sign? The phrase suggested a jingoistic pep talk from the 1980s car wars. Or after what happened in Atlanta, the tagline of a horror movie.

Yang Song is less remembered than Vincent Chin, but her untimely passing galvanized a movement of sex workers who formed the collective Red Canary Song.

The shooter there was a white teenager who killed six women at two massage businesses. He said he did it to cleanse himself off his own shameful desires. This motive made me think of a photograph Lee took of activists protesting the 1991 opening of Miss Saigon on Broadway. The musical follows the relationship between an American soldier and a virginal Vietnamese prostitute who commits suicide when the soldier rejects her. In this image, the woman closest to the camera holds a sign that feels too perfect as commentary on how the Atlanta shooter saw his victims. WE ARE REAL / “MISS SAIGON” IS NOT.

The angle of this sign does something unusual in a Lee composition, which are usually either shot head on or whose crowds obliterate the horizon. It creates the illusion of perspective. The window frames that repeat in accelerating rhythm, the faces of the protesters shrinking as they recede from the camera, and the diagonal of the police barricade slicing across the photograph—all these spatial cues suggest the impression of parallel lines converging toward a vanishing point just outside the frame. If we could pursue these lines beyond the image and even past the confines of New York City, perhaps they would lead to the Philippines, the only country where Miss Saigon conducted auditions for its lead actress. The same year Lee took this photograph, the American naval base there in Subic Bay employed 20,000 sex workers. In other words, to fully understand this photograph, we must see what its visuality does not capture: the way war erected zones of factories and also sex work. What the image does not show is how the American occupations brought into being both the factory girl and sex workers not unlike those represented in Miss Saigon and the women laboring in Atlanta.

One of the victims, Yong Ae Yue, met her husband while she sold train tickets between Seoul and Busan—he was an American soldier. Another, Daoyou Feng, had worked at factories in Guangzhou and Shenzen before she came to America and entered the massage business. You can see a similar economic trajectory in the life of a woman named Yang Song. Born in China, she worked in an offshore garment factory, then became a home health care worker in Queens, New York. While factory work and care work both rely on migrant women, the latter cannot be offshored since it requires the immediacy of touch. Yang Song eventually settled into sex work. This illegal status left her vulnerable to the police. One cop sexually assaulted her. Another pursued her when she fell from her fire escape and died in 2017, a tragic sequence for which the DA found no wrongdoing.

Yang Song is less remembered than Vincent Chin, but her untimely passing galvanized a movement of sex workers who formed the collective Red Canary Song. The group held a vigil for the Atlanta victims. Much of the event consisted of political analysis. The problem was not a deranged shooter, the women argued. Rather, because the state illegalized sex work, the women who worked at these businesses could not be protected by the police, as Yang Song’s story proved. One of the speakers, Emi Koyama, recounted how ICE swept the streets of Seattle specifically to capture undocumented sex workers. The solution, then, lay in decriminalizing sex work, abolishing the police, and opening borders. During the Vietnam War, the scholar Daryl Maeda writes, many Asian American women found themselves imagined by American men as prostitutes, typically the only Asian women with whom returning veterans had interacted. What if you could remove the man who mediated this triangulated relationship? Asian American feminists began to read about their counterparts. They brought women from Vietnam here. Some organized delegations to travel there. They preserved the memory of this encounter by carrying pictures of a female guerilla from the Vietnamese National Liberation Front. This is the implication of the sign in the back of the photograph. Don’t mess with my sister.

In 1993, Lee asked the actress Karen Lee to pose at the corner of Bowery and Canal. She raised a sword and cradled the New York Times in lieu of a bible. He had written a play starring Lee, Chinese Men Can’t Make Me Laugh, and now he had transformed her into an Asian American Statue of Liberty.

The photograph imagines the Asian woman not as a sex object, like in Miss Saigon, but a camp heroine of sword and newsprint, a wuxia warrior whose Shaw Brothers gallantry the city has rendered more mundane. An Amazonian poised above a street puddle, she flouts a NO STANDING sign to her left and finds herself duplicated on her right by Lady Liberty in her more official incarnation. Behind them, a storefront canopy reads HOME OF DIAMONDS, identifying America as the land of libidinous capitalism. I love the pedestrian simply waiting for the light, a mundane Asian unconcerned about the national archetypes arranged just a few feet away. Karen Lee, who described the shoot during the La Mama tribute, faced east as the early morning light filtered down Canal. Taxi drivers thought she was hailing them and kept pulling over, interrupting the shot to their delighted frustration. I wondered if one of them could have been Lily Chow.

In this photograph, Lee took the Asian woman banished to the periphery and put her at the center of the frame. After all, Asian women already formed the center of the American postwar project. Women of the global south, migrant women, women of color: these were the factory workers that permitted deindustrialization, the nannies who allowed white women to work. But can such a figure exist only as glorious iconography, outside of class relations? By the time Lee took the photo, his traditional subject, Asian proletarian women, had slowly disappeared from Manhattan’s Chinatown. Now he was depicting their imaginary doppelganger. Did he stage this photo because underlying economic forces had robbed him of his traditional subject? One could also say, more generously, that Lee’s creative practice, which began as an organizer’s utilitarian mimesis, had grown playful and imaginative. By taking a fabulist approach to the most literal art, Lee could interrogate his central passion: the problem of America.

After watching countless YouTube videos of Lee, the most emotional I ever saw him was when he described visiting the White House in a delegation for Asian American heritage week. As he photographed the queue of arriving guests, he saw First Lady Rosalynn Carter shake the hands of elderly Japanese Americans who’d languished in American prisons only years earlier—another national diptych. In the video, Lee looks nearly at the point of tears. He saw the encounter as a crucial moment where Asians and America found themselves redeemed in each other. As a child, Lee watched Martin Luther King, Jr. on television alongside his father, who told him that the Civil Rights movement would help Asians too. As an adult, Lee fought for Chinese-language ballot access in New York elections. He insisted that the “Asian American” was not a foreigner, enemy, or rival worker, but as someone deserving social citizenship.

Lee visualized this friction by colliding Asians against American symbols. Karen Lee mirrored the Statue of Liberty. Lily Chow fled Uncle Sam. But Lee’s most ambitious interrogation of American nationhood would create a juxtaposition as much temporal as spatial. In junior high, he saw a photograph taken on May 10, 1869. On that day, the western and eastern tracks of the Transcontinental Railroad were unified by a single golden spike at Promontory Point, Utah. America could now be imagined as a completed territory, but Andrew J. Russell’s famous photograph omitted the 20,000 Chinese men who comprised 80 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad’s workforce. Enduring whippings by their bosses and death from dynamite, these workers were abandoned by their white coworkers, who said they were incapable of self-organizing. When the Chinese rail workers did strike, their Chinese contractors halted their food shipments and let them starve in the snowy mountains.

The centennial of the golden spike was celebrated in 1969, and the Chinese Historical Society of America sent historians Philip Choy and Thomas Chinn to commemorate the Asian American contribution. But the Chinese American section was cut for time, leading Choy to upbraid Secretary of Transportation John Volpe in the men’s room. Lee also wondered what happened to the Chinese workers in the photograph. He decided to recreate the Golden Spike photograph, this time featuring their descendants.

After he passed away, I recalled that Corky had mentioned this gathering to me. He may have even invited me to attend. Watching his tributes, a sense of shame washed over me for not taking up the offer, but there was something about this project I didn’t quite understand. By imagining the Chinese back into the photograph, Lee performed what he called “photographic justice.” What did this uncharacteristically grandiose phrase actually mean? The Golden Spike project was a photojournalism of wish fulfillment, an attempt to use image-making, stagecraft, and community mobilization to correct what Michel-Rolph Trouillot called the silencing of the past. The project wasn’t just “reclaiming Chinese American history,” Lee said. “We’re reclaiming American history and the Chinese contribution is part and parcel of that.” But why did Lee, who castigated this country for its wars in Vietnam and the Philippines, want to reclaim American history to begin with? Lee’s father had lacked legal status and was a “paper son”—an unauthorized migrant who asserted citizenship from false documents, in a curious inversion of what we now call being undocumented. America did not end exclusion until Lee turned 18, after he’d already lived under the shadows of constant war in Asia. When Lee’s brother Jimmy served in the Vietnam War, according to Photographic Justice, the drill sergeant had him stand before his platoon and declared, “This is what the enemy looks like.” For someone saturated in this history, belonging was not a given. When Lee gathered his guests for an early Golden Spike photo shoot, someone announced on the loudspeaker, “Please welcome the Chinese visitors!” From his ladder, Lee yelled out, “We’re not Chinese visitors! We’re Chinese Americans, we’re Asian Americans!” Even when insisting they belonged in American history, Lee’s delegation looked like foreigners.

This anecdote’s many accouterments (loudspeaker, ladder, crowd-control) suggest that the Gold Spike photograph was more than a visual object—it was a continuation of Lee’s organizing efforts. Starting in 2002 and then annually from 2014 to 2019, the original photograph’s 150th anniversary, Lee convened massive and seemingly idiosyncratic gatherings at Promontory Point. Poets read their verse. Dancers leapt over the rail ties. An actor dressed up as a Buddhist monk. During the big shoot, Lee misplaced his lens and borrowed his partner’s, so even the camera emerged from this ferment of sharing and reciprocity, where new relationships bubbled and emerged. Another thing I did not understand about the Golden Spike project is how it left out a third community outside the white settlers and Chinese workers: the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Pawnee nations whose lands were severed by the railroads. And so, I found myself intrigued by Lee’s next project, which was announced by a woman at the La MaMa tribute. She called herself Corky Lee’s last friend. She was raised on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. Lee had told her that he wanted to explore the frontier alliances between Chinese and native communities, many of whom had intermarried. How did the two of them meet? Lee had joined the Sons of the American Legion in honor of his father’s service during WWII, and his last friend served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Four days after the planes hit the twin towers, Corky Lee photographed a Sikh man wearing his dastaar and a far more exotic ceremonial vestment, the stars and stripes. Approximately 2,500 Sikh Americans gathered in Central Park for a candlelight vigil. Some of them carried signs saying, SIKHS CONDEMN TERRORISM. Others held a banner expressing their grief over the 9/11 victims, which reminded me of another Lee photograph of a bindi-wearing woman holding a sign that says, OUR GRIEF IS NOT A CRY FOR WAR. In this image, I count six flags. What do we make of this exaggerated pageantry? Patriotism, grief, or violence prevention? Perhaps we may say that Lee’s photograph captures a moral provocation. The Sikh man demands the viewer look him in the eye. He demands you see him as an equal. As a citizen. Or at least as something other than a threat. The New York Press Association gave the photograph an award, but Lee found the award “marred,” in his words, by the judge’s galling citation: “Unusual juxtaposition of patriotism and ethnicity. The subject’s devious stare into the lens is compelling.”

Lee spent the days after September 11 sprinting across town. He photographed the ruins of the World Trade Center, as well as a modest shrine set up in Chatham Square, where the blockade of lower Manhattan would send three-fourths of Chinatown’s workers into unemployment. In Jackson Heights, he followed women marching for peace, South Asian domestics from the advocacy group Awaaz. Soon, the police would start spying on mosques and Muslim student groups. CCTV cameras would proliferate across the streets of New York and silently record wounded Asians two decades later. The man’s intense gaze, the way he demands that you meet his eyes—this is what everyone talks about what when they write about this photograph. After scrutinizing the image for a year, I found my attention gathering around the girl. She’s thinking something, just like the child at the garment factory. I am guessing she’s a second-generation kid, like Lee himself, burdened with the task of creating meaning from all of this. Her glance leans askew, almost suspicious, and she directs it towards something outside the compositional frame, a billow of dark clouds and thunderheads amassing in the distance.

The same day they raised their flags in Central Park, an Arizona man shot a Sikh man because he “wanted to kill a Muslim.” Balbir Singh Sodhi was not Muslim, just as Vincent Chin wasn’t Japanese, but he was the first casualty of the war on terror’s furious confusions. Last April in Indianapolis, a teenaged shooter made no such declaration when he murdered eight people at the country’s second largest FedEx hub, where 90 percent of the workers are Sikh.

Such warehouses draw in migrant workers because they require neither advanced English skills nor a degree, like the sweatshops and massage parlors raised to a far larger scale. Because fulfillment workers cannot be outsourced, our 21st-century labyrinths of logistics have erected new diasporic factory towns: Somalis in Shakopee, Latinx drivers in LA, Bhutanese in Columbus. Corporations decrease labor costs by hiring low-paid, non-union workers, a fact suggested by how the FedEx victims existed outside the usual lifespan of the worker. Most were retirees and teenagers.

I found myself curious about the lives of the women who had worked there. Amarjit Sekhon was a working mother. Her husband suffered a paralyzing disability, so she scrambled for every overtime shift she could find to support their two sons. She carpooled with her relative Jasvinder Kaur, who wanted to learn how to drive herself so she wouldn’t be stuck taking as many shifts as her workaholic carpool partner. Amarjeet Kaur Johal was another grandmother. Every day, she ate dinner at work, got in her car, and dialed her sister in India while she drove home. The perverse irony is that the male shooter typically feels exiled from society, while these Sikh women—who, like the Atlanta women, actually uprooted themselves from their motherland—had preserved the rich social fabric of family and community across the arc of migration.

So much of our vocabulary of representation comes premised on visuality (“I feel seen”), but I never saw myself in Lee’s photographs and that is why his work felt so crucial.

Shortly after Corky Less passed away, reporter Ti-Hua Chang wondered aloud on the news if Lee had caught Covid while volunteering for safety patrols in Chinatown. Hearing this struck me with an unexpected force, since Lee’s genius consisted of a profound inability to socially distance. How else would he be able to see you? His death was utterly preventable and would not have happened in a more nurturing state. He spent his last days believing that, despite the hostility against elderly Asians like himself, he should be out in the world with others. He spent his life looking at these streets. He knew them, he had nothing to fear from them. This is one of his last photographs.I only visited Manhattan a few times during the pandemic. One Thursday in fall 2020, I set off on a foolish bike ride from Columbia to Wall Street. An oncoming biker saw me and hollered, Jackie Chan! I pedaled faster. When I got home and saw the news, I glimpsed the woman who organized one of Corky’s tributes. Potri Ranka Manis, who founded the Filipino theater troupe Kinding Sindao, went to hand out masks in the subway and was attacked. I visited Chinatown for a haircut and my longtime barber, Cantonese by way of Vietnam, told me he might move to Shanghai. “It’s too dangerous around here, man.”

Newly trimmed, I waded into Canal Street’s frenetic mournfulness. Far more pedestrians flew by me than in Soho, but I also saw the occasional makeshift shrine for a slain Asian elder, the elegiac murals, and the vacant storefronts, negative monuments left by the seventeen restaurants and 139 stores gone out of business. Even Jing Fong had shuttered, the restaurant whose mirrored dining room hosted a certain belle monde of nonprofit banquets, community meetings, and Sunday dim sum. Closed down by a wealthy Chinatown landowner, Jonathan Chu, Jing Fong employed one of Chinatown’s last unionized workforces, whom Lee shot protesting about stolen wages in 1995. I’d heard that in those days, you could see the picket line overlap with another rally, the protests mourning Yong Xin Huang’s death at the hands of a cop. Roads come soaked in ghosts and traces. Jing Fong sat on Elizabeth, the same street as the garment factory where Lee photographed the child. Walk two blocks south from the restaurant’s shell and you will see a mural only recently painted on Doyers Street. The painting shows locomotives, a gang of old Chinatown toughs now quite elderly, and something you rarely see in Lee’s infinite archive. You see Corky Lee himself.

I spent a year looking at Corky Lee’s photographs. I saw grandmothers squat on the curb and laugh. I saw girls pluck the guqin. I saw boys pose on their fire escape. I saw women set up a streetside clinic whose sign says without shame: PAP SMEAR / BREAST EXAM / GONORRHEA TEST. I saw tenements, picketers, parades, veterans, and flags. I saw Reyna Elena, Miss Philippines and a B-Boy flying his bare arms wide. I saw a dapper Desi boy protesting Dotbusters. I saw men beat Taiko drums, I saw them hold up tombstones for Vincent Chin. I saw three women from Sakhi say: WE WILL NOT TOLERATE ABUSE. I saw a bride and groom order from a hot dog cart. I saw two cool women throw a cool glance. I saw a man remembering at a table marked POSTON ARIZONA and I wondered how many years had passed since the prison camps. I saw New York City and the tangled warrens of Chinatown. I saw a hollering woman in a hardhat hoist her sign high, the text that also tells her biography: INJURED ON THE JOB, THEN FIRED BY THE BOSS! There is something moving about the sheer number of people Corky Lee thought were worth remembering. His archive is an Aleph in which you can glimpse everyone from an Asian American world bulging vast with time and complexity. Over the past few years, we have asked for someone to finally see us. Looking at these kaleidoscopic images, I found myself thinking the only power that can recognize us is ourselves.

So much of our vocabulary of representation comes premised on visuality (“I feel seen”), but I never saw myself in Lee’s photographs and that is why his work felt so crucial. “Identity” suggests something private and individual—and when looking at who Lee photographed, I was struck by how no one alive could literally see themselves in every portrait. They showcase the difference at the heart of “Asian America.” Today, people often remark that Asian Americans don’t have anything in common, that nothing really unites us. What they are really wondering is why they don’t feel the magic of their own self-essentialism. The Sikh flag-bearer, Miss Saigon protester, and Chinese seamstress do not resemble each other, but Lee honored them into a portraiture that implied some larger commonality, a coalition that need not be constricted by nationalism. We live in a moment of Asian American fear, but looking at Lee’s photos, I thought about the tremendous courage it would take to proffer yourself to a country that pictures you as its adversary. I considered the bravery required to rebut a cop, push back against your boss or transplant yourself from your home into some dismal American sweatshop. Unlike identifying with someone just like you, solidarity suggests “you” constitutes something suppler than the cell of yourself.

His prints emanate a heterogeneous light. They are mirror that reflects a different person than their onlooker. I think the last time I ran into him was in 2018. I’d thrown on a navy suit to visit City Hall for Asian American heritage month—an event Lee inaugurated at the White House decades before. Late May, early June: spring had begun transitioning into summer, that time when New York begins to turn grand and glorious. The frail light of dusk scattered golden across the street and as I strode in, I saw a few elderly women sitting on the sidewalk. Their signs said they refused to eat. Their landlord had thrown them from 83 Bowery and so they decided to go on hunger strike. And there was Corky Lee, snapping their picture.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.