Chris Hedges on Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia

In his book "Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia," John Gray warns that as the era of liberal intervention in international affairs wanes, it is being replaced with "primitive versions of religion" that will be used to fuel apocalyptic violence.In his book “Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia,” John Gray warns that as the era of liberal intervention in international affairs wanes, it is being replaced with “primitive versions of religion” that will be used to fuel apocalyptic violence. His is a world where faith-based violence will become the norm, where societies will plunge headlong into self-immolation and where desperate groups of people will soon battle in a Hobbesian struggle for dwindling natural resources.

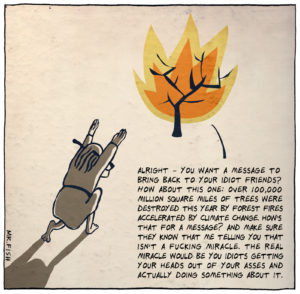

Gray pleads, like a modern day Cassandra, for us to heed the numerous warning signs, from the effects of climate change to the rapaciousness cruelty of global capitalism to the looming oil crisis to overpopulation. He fears, however, that as things worsen, we will spurn pragmatic measures to blunt the excesses – he does not believe we can reverse them — for fantastic, violent visions spun out for us by mad utopians. His book is a plea for sanity. I hope it works.

Gray is one of the most interesting moral philosophers since the Christian theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Gray would, I expect, label Niebuhr as an idealist, given that Niebuhr, while conceding our animal natures and irrational delusions, did believe in the possibility of limited free will. Gray is more skeptical; he sees us as all hostage to our animal instincts and argues that we can do little to blunt them. This is Gray’s greatest failing, for he does not, like Niebuhr, make distinctions. Yes, we are all flawed, but not equally flawed, and it is because of this that free will and moral choice remains possible.

“Actually, humanity cannot advance or retreat,” Gray writes, “for humanity cannot act: there is no collective entity with intentions or purposes, only ephemeral struggling animals each with its own passions and illusions.”

But Gray is with Niebuhr on many other issues, including a dark view of human nature that does not ignore the capacity we all have for cruelty, depravity and self-delusion. Gray seeks, like Niebuhr, to be a realist. This makes his writing, unlike many modern philosophers and theologians, worth reading. And unlike most of his colleagues, he does not take refuge behind the mind-numbing jargon and the dead language of academia that is, at its core, anti-thought. He builds his ethics on the foundation of the stunted and limited capacity of human nature, rather than visions of human perfectibility and delusions about human progress. He knows that we do not advance morally as a race, and that it is science and technology that have at once improved our world and made the vast killing projects and environmental devastation of the last century possible.

“Human knowledge tends to increase,” he writes, “but humans do not become any more civilized as a result. They remain prone to every kind of barbarism, and while the growth of knowledge allows them to improve their material conditions, it also increases the savagery of their conflicts.”

Gray also grasps that the religious impulse does not go away, even in ruthlessly secular regimes such as the old Soviet Union. They simply mutate and transform. He warns that these unexamined impulses are more dangerous than those overtly embraced by traditional religion. He charts the decline of Christianity as coinciding with the rise of revolutionary utopianism. These eschatological hopes never disappeared; rather, they muted into a form of secular fundamentalism, peddled by fascists, communists, liberal humanists and by the naïve crop of new atheists such as Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennet.

“Those who demand that religion be exorcized from politics think this can be achieved by excluding traditional faith from public institutions; but secular creeds are formed from religious concepts, and suppressing religion does not mean it ceases to control thinking and behavior. Like repressed sexual desire, faith returns, often in grotesque forms, to govern the lives of those who deny it.”

The culprit is the Enlightenment myth of human progress and its belief in human perfectibility. It was this myth, embodied in the widespread embrace of pacifism in the aftermath of World War I, which also terrified Niebuhr. The delusion that human beings could advance morally led directly to despotism.

“Whether they stress piecemeal change or revolutionary transformation,” he writes, “theories of progress are not scientific hypotheses. They are myths, which answer the human need for meaning.”

Gray, in his effort to be a realist, can stretch himself too far. He buys into a little too much of E.O. Wilson’s myth of biological determinism.

Gray warns of the moral corruption of the Bush’ administration’s open embrace of torture a form of interrogation.

“The methods of torture employed in Iraq targeted the culture of their victims, who were assaulted not only as human beings but also as Arabs and Muslims,” he notes. “In using these techniques the US imprinted an indelible image of American depravity on the population and ensured that no American-backed regime can have legitimacy in Iraq.”

The world that awaits us will be difficult. It will require, as Gray understands, “stoical determination and intellectual detachment.” It is not a world where we want “missionaries and crusaders” like George Bush and Tony Blair, who see every crisis “as a heaven-sent opportunity to save humanity.” The coming world will require a return to realism, to the belief that we cannot mold and shape the world according to human desires but must carry only out piecemeal and very limited acts of social engineering to ward off the worst effects of the disasters that will befall us. Politics, he knows, is not “a vehicle for universal projects but the art of responding to the flux of circumstances.” This means we must give up our grand visions for humanity to “cope with recurring evils.”

“Realists do not accept that international relations, any more than human life in general, consist of soluble problems,” Gray notes. “There are situations in which whatever is done contains wrong – for example, the situation that has been created by American intervention in Iraq. Certainly we can avoid multiplying these situations: we may have to deal out mass death to defeat Hitler but we need not wade in blood to democratize the world. Realism is an Occam’s Razor that works to minimize radical choices among evils. It cannot enable us to escape these choices, for they go with being human.”

Gray concedes that religion, when it is not hijacked by fundamentalists or starry-eyed idealists, keeps us grounded. His work is a potent and powerful meditation on human nature and the concept of sin — the core of great theology. He writes that religion is an attempt to deal with mystery “rather than hope that mystery will be unveiled.” He calls this “a civilizing perception” and fears that it is being lost.

What Gray fails to grasp is the transcendence and power that comes with achieving the moral life, a life a realist has to concede is absurd. There is a meaning to existence. It is found, as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Joseph Conrad and Vasily Grossman knew in simple, blind acts of human kindness, especially towards the outcast and the stranger. It is discovered when we confront and acknowledge the inevitable chains and limitations of human nature but do not completely succumb to them. These small acts of compassion, never free from the taint of self-interest, do not make the world a quantifiably better place. We will not be rewarded for them. We will not save ourselves from evil, suffering and death. But these acts mean that we have, if only for a moment, felt what it means to be fully human. We have reacted not as animals in a herd, but as individuals who rose above our baser instincts and the clamor of the mob to defy hatred and bigotry and to cherish life. These acts of compassion allow us to become conscious, if only for a moment, in an unconscious world. And these acts define and sustain the religious life.

Chris Hedges, who graduated from seminary at Harvard Divinity School, was a foreign correspondent for two decades in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans, most of that time with The New York Times. He was part of the team of reporters at Times who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2002 for their coverage of global terrorism. He is the author of “War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning” and “American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America.” He has taught at Columbia University, New York University and Princeton University and is currently a senior fellow at The Nation Institute. Hedges writes a bi-weekly column that appears Mondays on Truthdig.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.