Caroline Moorehead on the Exemplary Life of Lesley Blanch

A new biography of the remarkable writer Lesley Blanch suggests that living well—which may be the same thing as living passionately—is the best way of blunting the force of time’s arrow.A new biography of the remarkable writer suggests that living well is the best way of blunting the force of time’s arrow.

This review originally appeared in The TLS, whose website is www.the-tls.co.uk, and is reposted with permission.

When, towards the end of the 1960s, Lesley Blanch came to write her autobiography, Journey into the Mind’s Eye, she wove it around the story of a first great love, a man she named only as the Traveller. A Tartar from the great steppes, with slanting eyes and amber skin, infinitely exotic in his fur-lined greatcoat and soft leather boots, the Traveller came to her nursery and told her tales of hump-backed horses, stuffed sturgeon and Mongol warriors.

He sent her gifts from the bazaars he visited on his travels and called her by Russian nicknames until she found herself living in a fabled parallel dream world. When she was seventeen, he took her on an overnight train to Dijon and they pretended that it was the Trans-Siberian Railway. She learnt to love him “properly”, and believed herself engaged. But on her twenty-first birthday, along with a prayer mat and an icon, came a farewell letter; she never saw him again.

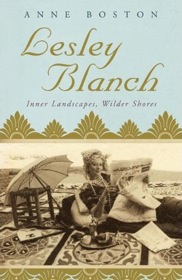

Did the Traveller exist? Almost certainly not, at least not in the form in which she cast him. There was no charming nursery or aristocratic parentage, as Anne Boston discovered when she embarked on her biography of Blanch [“Lesley Branch: Inner Landscapes, Wilder Shores”], but a semi-detached in Chiswick and two grandfathers who were both skilled tradesmen. But the mythical Traveller, conveniently coming at a moment when all things Russian were in vogue, gave her a delight in samovars and patterned kilims, in tapestries and rooms full of low tables and brightly coloured silks and in the notion of travel, to remote and extraordinary lands. Blanch once described Aimée Dubucq de Rivéry, one of the heroines of The Wilder Shores of Love, as “character plus opportunity equals future”. The words might be Blanch’s own epitaph.

Born in 1904, Blanch was sent to St Paul’s Girls School [in London], where her teachers complained that she lacked team spirit, though she showed some talent for art. She left at sixteen, prodigiously well read and very pretty, with curly fair hair and a will of iron. What she called her “run-away game” allowed her to escape in her mind to tented nomad encampments and the mountains of the Caucasus, which she called the “landscapes of my heart”. A brief stint at the Slade [School of Fine Arts] taught her to draw, illustrate and decorate, and she began to earn her living designing book jackets and posters. She was so pretty that she was always surrounded by men, but they were never exotic enough and they bored her. She liked to dress up, usually à l’orientale, and she made friends with the Sitwells, Harold Acton and Peter Quennell. Unhappiness was not something she was prepared to dwell on: an illegitimate daughter seems to have been put up for adoption and forgotten.

Blanch made a first marriage, at twentyfive, to an advertising agent called Robert Wimberley, but soon realized her mistake. Among the affairs that followed was one with the theatre impresario Komisarjevsky — memorably nicknamed “come-and-seduce-me” by Edith Evans — who was satisfactorily oriental but not a man to commit himself. In the summer of 1935, needing to make money, Blanch wrote a first article for Harper’s Bazaar on the tyranny of beige. She had an easy, natural style, an unusual imagination and considerable energy; and she was happy to write about everything from bad English food to a new ballet by Diaghilev. Before long she was features editor on Vogue. When war came, Blanch and the photographer Lee Miller travelled about in search of patriotic subjects.

In 1944, when London became the capital of the Free French, she met another version of her Traveller. Romain Gary was Lithuanian, an airman with a Croix de Guerre who had a long face like a Russian icon and who had written a novel (Éducation européenne). Her friends referred to him as “Lesley’s frog”. Gary was ten years younger, and as steeped in his own mythologies as she was in hers. For a while, their marriage survived on mutual infidelities. When Gary joined the French diplomatic service and was posted to Bulgaria, Blanch went with him, as she did later to New York and Hollywood, where he became a sort of French ambassador to the stars. But Gary was limitlessly selfish, capricious and philandering, with a taste for young girls, and the marriage foundered when he found literary fame with Les Racines du ciel (1956; The Roots of Heaven) and went off with the gamine Jean Seberg.One of the most unexpected sides to Blanch’s character was her dedication to work. Extremely versatile, turning her hand to design, painting, fiction, journalism and history, she never stopped working. Boston conjures up a pleasing scene of the two of them at work, Gary at one end of the house and Blanch at the other, barely meeting, each wrapped up in a cocoon of ruthless creativity. While she wrote, she listened to Bach, Bob Dylan, or reggae; but not Wagner, which she saved for serious listening.

Blanch was almost fifty when she finished her first book, The Wilder Shores of Love, an instant bestseller about four romantic runaway nineteenth-century women, anticipating what would become a stream of biographies of intrepid lady travellers. Though never as successful, other books followed, along with dozens of articles, often the result of journeys to the places she had dreamt about. Russia, the Middle East and India were the settings she loved. For all the blond curls and winning ways, she was a meticulous, tireless researcher, ferreting out facts in libraries and archives all over the world, tracking down her subjects and their descendants in inaccessible places. More serious and scholarly than she appeared to be, she was also more driven.

With her first book, Blanch had the incomparable good luck of finding Jock Murray as her editor, a man whose generosity of spirit and patience with his authors — among them the no less demanding and imperious Freya Stark and Iris Origo — became legendary. It says much for their relationship that she kept a pair of embroidered slippers at Murrays, to wear when she went in to correct her manuscripts.

He nursed her through her first five books, providing stability as she lurched from drama to drama, and felt understandably hurt when she took the next to another publisher, though they remained friends.

After her break-up from Gary, which, for all his waywardness and self-obsessive gloom, upset her greatly, she somewhat surprisingly went back to Hollywood to work with George Cukor on a film adaptation of Lady L, Gary’s novel whose heroine is based with unnerving exactness on Blanch herself. She was to be seen pedalling around the studio lot on a bright red bicycle, checking that the extras were wearing authentically French costumes. When she turned to her own autobiography, the interplay between fact and fiction, reality and imagination, became her way of reinventing a past and a world that she would have loved, much as one clings on to a pleasing dream long after waking, to enjoy the happiness it casts. In glorifying this first great love with the Traveller, she was able to so diminish Romain Gary that he became little more than a footnote in her life.

This is not an authorized biography, and Blanch’s literary executors refused Boston permission to quote from her letters. To Boston’s credit, she keeps speculation to a minimum, but the absence of letters is a serious drawback, for they would have added the very important dimension of Blanch’s own voice. On the very rare occasions when she is able to quote something — as with Blanch’s charming description of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, “tiny twins with large bottles of drink” — it makes the reader realize what is missing. Perhaps because of these absences, Boston devotes much space to Gary, whose reimaginings of himself reached epic proportions.

The gap left by the absent letters is all the more regrettable in that Boston’s biography is both entertaining and scrupulously researched and there will surely never be the need for another.

When Lesley Blanch was ninety, her house in Menton, on the Côte d’Azur, close to the border with Italy, burnt down. She escaped in her nightdress unharmed just as the roof caved in, but her entire lifelong collection of silks, carpets, icons, portraits and papers went up in the blaze. It was in keeping with her determined nature that she decided to rebuild the house, and was soon once again surrounded by silks and tapestries, many of them found in local junk shops and flea markets.

Blanch lived until just before her 104th birthday, charming interviewers with her sharp tongue and flights of imagination and taking care to give nothing away, and she survived long enough to see many of her books reprinted. The woman who emerges from Anne Boston’s book may indeed have been ruthless and a fantasist; but there was something endearing and even admirable about the stylishness and panache with which she concocted her life.

|

Caroline Moorehead has written biographies of Martha Gellhorn, 2003, Iris Origo, 2000, and Bertrand Russell, 1992. |

This year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.