Carla Kaplan on ‘The Mitfords’

A new collection of letters between the fascinating Mitford sisters offers unparalleled insight into one of the 20th century's most famous families.

by NPR’s Scott Simon, Deborah Cavendish, the last of Britain’s famous “Mitford Girls,” or “Mad Mitfords,” as they were also known, couldn’t help giggling at her title: “the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire.” “Such a mouthful,” she remarked, as her interviewer tried not to stumble. The Mitford sisters’ ability to laugh at their own lives and encourage others to do likewise is an essential part of their charm. Their delightfully irreverent humor — the “Mitford Tease” — is everywhere evident in Charlotte Mosley’s new volume, “The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters,” just published by HarperCollins. This engaging collection is at once a paean to the dying art of letter writing, a moving chronicle of the complex and contradictory dynamics of family and, most surprisingly (given the Mitfords’ much vaunted girlishness), a compelling account of aging. “Don’t let’s live to be too old, it’s no fun,” one sister writes to another, in what could be this book’s motto.

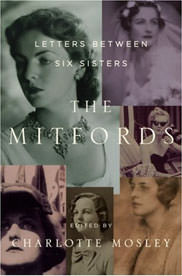

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters

By Charlotte Mosley

Harper, 864 pages

Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters

By Carla Kaplan

Anchor, 912 pages

The Mitford sisters were once so notorious that, as Mosley points out, “hardly a week went by during the 1930’s without one of the sisters making headlines.” They were famous for their beauty, their wit, their eccentricities, for being the children of great privilege and wealth, for going in remarkably different directions — a novelist, a chicken expert, a Fascist, a Nazi, a Communist, and a Duchess — for witnessing almost every major historical event of the 20th century (to which they provide a peculiar kind of guided tour here, minus some of the commentary one might expect) and for knowing seemingly everyone (the range of their acquaintance alone imposes an editorial burden, encompassing both Hitler and John F. Kennedy, Evelyn Waugh and Maya Angelou, Katherine Graham and James Forman, Bertrand Russell and Emerald Cunard, Lucian Freud and Julie Andrews, Queen Elizabeth and Jerry Hall). Perhaps they were most famous, however, just for being so famous. Part of this book’s story is what a lifetime of modern celebrity does to women, as well as what it’s like to hanker for that kind of fame.

The Mitford legend begins with the parents, Lord and Lady Redesdale, a quirky couple remarkably unself-conscious about their own eccentricities. Lady Redesdale, for example, refused to send her daughters to school or have them play with nonfamily members because she considered “the company of other children unnecessary and overstimulating.” Nancy, the eldest, became a famous novelist (“The Pursuit of Love” and “Love in a Cold Climate”). Pamela, the second-oldest and the least public, became a poultry expert, and probably a lesbian. Diana married Oswald Mosley, the head of Britain’s Fascist party, and refused ever to denounce her admiration for Hitler. Unity Valkyrie, universally described by the other sisters as courageous, honest, loving and loyal, became a dedicated Nazi, tremblingly passionate about Hitler, and shot herself in the head (but failed to kill herself) when Britain and Germany went to war. Jessica, the second-youngest, ran away at the first opportunity with her second cousin, Esmond Romilly (Winston Churchill’s nephew), joined the American Communist Party and became a civil rights activist and a muckraking journalist (“The American Way of Death” and “Kind and Usual Punishment”). Deborah, the youngest sister and the last survivor, became a very successful businesswoman as a duchess, turning the impossibly immense Chatsworth estate into an attractive tourist destination. As Christopher Hitchens once put it, “the Brontë vicarage at Haworth seems humdrum by comparison.”

It would be an understatement to say that much has been written about the Mitfords. But few accounts provide as wonderfully messy and intimate a story as do letters. Mosley’s book was preceded by her two other collections of Nancy’s correspondence and, more recently, by Peter Sussman’s excellent and long-awaited collection of Jessica’s letters. Here, we have all six of the sisters at once, although Nancy, Diana and Deborah dominate the conversation (Unity’s letters drop off after her shooting, Pamela does not write often, and the bulk of Jessica’s fascinating letters are written to others). Nonetheless, “The Mitfords” takes us both through eight decades and backstage of the familiar Mitford legend. We are able to overhear the sisters’ loathing of their own popularity. “The whole phenomenon was invented by the newspapers. … The bits I read made me think once again how ghastly all Mitfords sound, though of course in real life ha-ha they are ideal,” Diana writes. “I do wish people would stop writing books [about us],” Deborah laments. “I must say I wish they’d leave us alone.” But at the same time, we also see just how much the sisters did to nurture and construct the very legend they all profess to despise, taking a certain delight in the overexposure that also annoyed them. “I must admit ‘The Mitfords’ would madden ME if I didn’t chance to be one,” Diana writes, making it clear what a point of pride it is to “be one” of the famously maddening sisters. However unhappy the sisters may claim to be as legends, this collection reveals the extent to which that legend was of their own making and, moreover, how living as a legendary Mitford was a delight — and a “bother” — that they all felt only another Mitford could know.

If this is not the best place to turn for an understanding of the Mitford sisters’ puzzling politics — these letters rarely engage such questions — it is an excellent way to understand what it might have been like to be a member of this infamous, hysterically funny, fierce and riven sisterhood; what it was like to be a member of such a remarkable group of women; how their bonds to one another survived; and, most poignantly, how they were finally broken, despite affections for one another which ran deep indeed. Nancy once said that she pitied children without siblings because they didn’t have anybody “to stand between them and life’s cruel circumstances.” Sisters, Jessica retorted, “were the cruel circumstances.” As we can now see, there was a great deal of truth on both sides. Childhood grievances never lessen or die among the sisters, and false accusations and mischaracterizations rankle beyond all rational explanation; this may feel familiar to many of us. As we might expect from such a volatile, opinionated and stubborn group, the sisters are continually getting on and off “speakers” and “stayers” with one another (except for Jessica and Diana, whose political differences put them on “non-speakers” for life). Despite their need for one another (no one else, after all, really got what it was like to be a Mitford sister), they were often, in Nancy’s words, “not very sisterly.” They betrayed each other, lied to each other, deceived each other, mocked each other, complained about each other, spied on one another and often despised each other. Their challenge — and they rose to it often nobly and always instructively — was to try to accept one another, with their differences intact. “Nothing I can say wd changer your view of things & ditto the other way around if you see what I mean,” Deborah wrote to Jessica. Since their identities were so mutually and collectively formed, rifts and silences between them were devastating. “Don’t we all sound horrible. … Perhaps we are, but we do at least all love each other,” Diana wrote.

Throughout their lives, they continued to “long for” one another as they did for no one else. “I long for you. Every time I look at the bookcases I think of you. … I do simply so long for you sometimes, you can’t think,” Nancy would write. “I long for ALL sister ALL the time,” Deborah noted. The sisters lived on a very large world stage. But it was their approval of one another that each of them usually craved. “I always think while I’m writing you how terrifically you despise my life,” Deborah wrote to Jessica. “For some reason I longed for, but feared, your reaction more than anyone’s, even the reviewers. So I was most awfully glad to get your letter,” Jessica wrote to Nancy.

It is not merely approval these women crave from one another, but correspondence itself. One gets the sense that what these women long for when they long for one another (which is very often) is not so much an actual physical presence of their sisters (though some of the sisters did very much enjoy one another’s company, especially for brief visits) as it was the very particular experience letters provide: a shared sensibility and an intimate — but controlled — “girl talk.” “What would one do without your letters,” Deborah writes to Diana, “it would be a grey waste.” “Oh Debo your letters literally do make my life,” Diana writes to her. There is a sustenance and comfort to be had from letters which is unlike anything else and, as we see across these sisters’ long lifetimes, which phone calls (which demand immediate reciprocation), e-mails and text messages can never replicate (no wonder that Jessica willed $5,000 to her postman). In a letter from 1975, Deborah writes to Nancy about the special quality of letters and anticipates this very book and its author’s efforts. “I usually keep Valuable Envelopes if the letters are two page affairs, like yours of yesterday with the unmasking news. Otherwise I’d pity the monkey’s orphan (Brill person of about the year 2000 who will make a thrilling, silly book on the Last Correspondence Between People using Pen & Paper) who would have to put the thing together.” This “thrilling, silly book” is one of the last great surviving groups of letters, and the sisters knew what an invaluable archive it was. Nancy wrote Diana in 1963, “Throw nothing away … a correspondance suive of a whole family, so rare nowadays, would be gold for your heirs.”

Selecting, dating, ordering, editing, cutting and annotating the more than 12,000 letters the sisters wrote to one another was truly a labor of love on Mosley’s part. Because this collection contains only 5 percent of their correspondence and those which are included here are rarely complete (excisions, cuts and excerptions go, unfortunately, unmarked), the view we get of the sisters’ lives and relations with one another is necessarily partial. But because the sisters are allowed to speak in their own voices, with minimal editorial intrusion, however “fragmentary” (Mosley’s term) an account this may be, it also feels authentic. For those unfamiliar with the Mitfords, this collection provides an excellent introduction (thanks, in part, to helpful interchapter overviews, footnotes (American readers, in particular, will occasionally want footnotes to the footnotes), a family tree, many photographs, an index of nicknames, a comprehensive index but, surprisingly, no bibliography). For the many Mitford fans who already feel they know the sisters, “The Mitfords” may offer several surprises.

This volume offers an unusually inside look at British aristocracy, especially its often-noted aversion to both emotional expression and physical labor. The sisters are astoundingly inept domestically and they simply revel in their own inability to do laundry, wash dishes or iron:

“Darling, housework. I make my bed & wash up a coffee cup & then I go to bed & sleep the sleep of utter exhaustion until dinner time. What does it mean & how can people manage? I never attempt the Hoover or lighting the stove or any of the moderately tough things,” Nancy writes.

American readers, in particular, may be surprised to see the low opinion many of the sisters had of European “high culture.” The Duchess of Devonshire, for example, dismisses opera as a bunch of “fat screamers,” hopes that she can avoid reading the classics her sister Nancy recommends to her (“Oh Proust,” she writes, “shall I try now or is it too late? I do hope it’s too late”) but is enough of an Elvis fan to make two trips to Graceland. “Oh Graceland,” she writes, “The excitement was intense, please picture. … A sweet but hopeless black girl in a woolly hat was our guide but the audios made her not necessary. They were perfect, Priscilla Presley talking, & sometimes Elvis plus music, allowed one the right amount of time in each room. The furniture was too lovely, white ‘custom made’ sofas all along a wall, down 3 steps & a white piano on a shag carpet so deep it went 1/2way up its legs. The Jungle Room had outsize chairs whose arms were carved crocodiles’ heads, enormous, & a vast round one which no one could sit in because of its depth. Green carpet 2 inches long, (thick) & the same on the ceiling. Do admit. Alas no upstairs. … Then across the (very main) road to see his aeroplane — enormous, with a huge bed in it. By then we were whacked & only got to one shop & the idiotic Morticia never told us there were 2 more so we missed the sequin tee shirts & such like, maddening.” The duchess’ very British love of American kitsch is one surprise — particularly in light of Nancy’s hatred of America and all things American (“that land of dire hypocrisy, where … no birds sing, no flowers smell, no food tastes.” But Deborah herself, or “Debo” as she is known to her sisters, is often surprising. (She is also the volume’s undeclared favorite, and her generosity of spirit, aversion to conflict, and tendency to see politics and extremism as synonymous all find favor with the editor, who happens to be the daughter-in-law of the ideologically unrepentant Diana Mosley.) While not known as a writer, Debo turns out to be almost as funny a correspondent as Nancy, Diana or Jessica, with an equally cunning eye (and ear) for telling detail. For example, from the family’s island, Inch Kenneth, to Diana in Holloway Prison (where Diana was interned during World War II because of her pro-Fascist views), for example, Deborah writes:

“Darling Honks

Muv [mother] says one can write to you at last, Oh I do so long to see your cell. I haven’t seen you or your pigs [the sisters’ term for children] for such ages that I’ve almost forgotten what you look like what with one thing and another. …

I can’t think of anything fascinating, nothing much occurs here. Farve [father] is either in fits of gloom or terrific spirits, apparently for no reason. I hope he won’t live here alone in the winter because gloom is usually the form & what it must be like here then I can’t imagine. Lividry sets in when my goat eats his creepers etc exactly like it always did, he is an eccentric old fellow.

When we were climbing around the caves here the other day I heard the most terrifying sound just like a hermit tearing calico, it so horrified me that we haven’t been round there since. It has become the stock joke & thing to be frightened of, oh the horror.”

The sisters’ small delights are often most endearing, such as their willingness, even as distinguished middle-aged women, to make ridiculous “Boudledidge” faces and be photographed doing so (Mosley includes two absolute gems, one of Deborah and Jessica at Chatsworth and a later photo-booth one of Jessica alone), their love of sounds and nicknames (each sister had a plethora), their fondness for animals (from chickens, dogs and sheep to stray owls, backyard hedgehogs and turtles, and the miniature horses which Nancy called “insects”), and their frequent self-awareness of the many ironies of their own class and national privilege — what Deborah calls “being a pariah.”

They are most alarming, on the other hand, in their responses, or rather their relative non-responses, to what we would term the larger and more serious events of life: children’s deaths, husbands’ infidelities, Nazism, concentration camps and so on, things about which, here at least, they have remarkably little to say. Unity’s impassioned descriptions of Hitler (which take up altogether too much space in the beginning of the book) read like those of a teeny-bopper, wild for one of the Beatles: “Such a terribly exciting thing happened yesterday. I saw Hitler. It was all so thrilling I can still hardly believe it. If only Putzi had been there!” And again: “The Führer was heavenly, in his best mood, & very gay. There was a choice of two soups & he tossed a coin to see which one he would have, & he was so sweet doing it. He asked after you [Diana], & I told him you were coming soon. He talked a lot about Jews, which was lovely.” One wonders if she ever understood what was at stake. Diana, on the other hand, who clearly did understand, evinces a lifelong anti-Semitism, racism and denial of political realities — as late as 1975 she ranted about “Jews who are stopping him [Mosley] from getting a university appointment” and claimed that “most of the violence” involving British Fascists in the war came from “Jews attacking Kit’s people in dark lanes etc.” — which remains as hard to understand as her own confident claim to “hate unfairness,” or her sisters’ clear sense that, personally at least, that statement rang true. This is a volume filled with such questions and contradictions. Mosley lets them stand. In 1996, after Jessica’s death, Deborah wrote: “Reading the obits. of Decca, the Mitford Girls are described, variously, as Famous Notorious Talented Glamorous Turbulent Unpredictable Celebrated Infamous Rebellious Colourful & Idiosyncratic. So, take your choice.” And at its best, this book encourages us to do just that.

“The Mitfords” gets more compelling as it goes along and as the sisters, in the second half especially, become more and more complex (making the simplified tagging system that Mosley cleverly designed to identify each sister — swastika, hammer and sickle, and so on — seem increasingly problematic, ironically creating just the effect of “Nazis all the way,” for example, which Deborah feared in others’ simplifications of Unity). Their stories of surviving the war to face the indignities of illness and death are especially moving. It is hard not to be touched by seeing these indomitable and seemingly unstoppable women laid low by blindness, deafness, headaches, tumors and cancers, in part because they focus on the most concrete details of their own decline: “Darling Debo, Debo my hair. Don’t laugh. It’s … a shaving brush,” Diana writes. They struggle valiantly to keep up their trademark breezy, ironic understatement, and it is impossible, watching them do it, not to cheer them on.

The sisters speculated that their letters could never be published while any of them were living. “I also think a vol of letters will have to wait until everyone’s dead, don’t you, because of hurt feelings?” Diana wrote to Deborah. But in bringing these letters to light now, the remaining Mitfords — the Duchess of Devonshire and Jessica Mitford’s two children, Constancia “Dinky” Romilly and Benjamin Truehaft, especially, all of them public people — have, to their great credit, replaced stock figures with complex and, hence, more three-dimensional women. “It’s not too easy to know what anyone is really like,” Deborah wrote to Jessica. But as she also wrote to Diana, “it’s the humanizing we’re after so Carry On Honks.”

Carla Kaplan is the Davis Distinguished Professor of American Literature at Northeastern University, a fellow at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard University, and a Guggenheim fellow. Her books include “Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters” and the forthcoming “Miss Anne in Harlem: The White Women of the Black Renaissance.” She is also writing a biography of Jessica Mitford.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.