Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice Is Saying ‘No’ to the War on Drugs

A group of Latin American activists is winding its way to New York City, where it will participate in a special session of the U.N. General Assembly in order to shine a spotlight on the global horrors wrought by the illicit drug trade. Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice

Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice

A group of Latin American activists has embarked on an extraordinary journey through Central and North America to call attention to the multiple intersecting issues surrounding the global war on drugs. The Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice started out in Honduras on March 28, where communities are still reeling from the murder of prominent indigenous environmental activist Berta Cáceres. It then headed to El Salvador and Guatemala, picking up more people, before entering Mexico. On April 19, the caravan will end its journey in New York City, where a special session of the United Nations General Assembly on the World Drug Problem will be held.

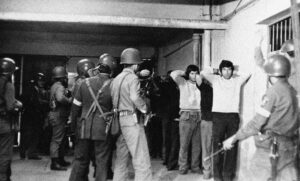

Untold numbers of people have died or disappeared in Central America and Mexico as a result of crimes related to the drug war. Powerful narcotraffickers have bought politicians and control paramilitary forces. Rampant violence and poverty have prompted an exodus of refugees heading northward. Across the border in the U.S., the drug war’s refugees are criminalized and housed in prisonlike detention centers, while African-Americans are disproportionately incarcerated for drug sales and use.

The fallout from the drug war is wide, deep and terrible. Across multiple borders, it ties together global poverty, violence, immigration, incarceration and addiction, for which elected officials offer no real solutions.

Parents and loved ones of those who have disappeared, tired of political inaction, have joined the Caravan for Peace, Life and Justice. They march in cities, carrying photographs of their lost sons and daughters. Also on board are clergy and other faith leaders, journalists and activists. Among them is Laura Carlsen, director of the Americas Program of the Center for International Policy in Mexico, and a columnist for Foreign Policy In Focus. In an interview on “Rising Up With Sonali,” conducted from an Internet cafe in Guatemala City, she explained how in Honduras the “drug war has been a pretext to militarize.” The late Cáceres was a core organizer of the caravan, primarily because a lot of the drug money in Honduras flows into large-scale development projects, such as the hydroelectric dam she was mobilizing against.

The path the caravan is taking parallels the path that tens of thousands of refugees have taken over the years as they have headed north from Central America to the United States, passing through Mexico. Most undocumented immigrants from Central America are refugees fleeing the violence of the drug war, as award-winning journalist Sonia Nazario has detailed in The New York Times. The same money being funneled into cracking down on drug trafficking is also used to police borders and crack down on the migrants that cross them.

Carlsen described the overlapping issues as “a vicious circle for many of these people where, because of the increased violence of state repression, and the destabilization of an illicit drug trade, they’re forced out of their own countries—whether it’s Honduras or El Salvador or Guatemala.” When refugees reach the Mexico border, some are murdered, and some are deported back to the violence they fled and then murdered in their home countries. Those lucky enough to make it to the U.S. border find “this conflation of border security, counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics [that] has created a build-up of repression around the border,” according to Carlsen. And, as we know, if they manage to cross the border, they face the difficulties of living in the shadows.

Just days after the caravan embarked on its symbolic journey, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released the Panama Papers, a trove of 11.5 million documents leaked from the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca, detailing how the world’s wealthiest elites—many of them politicians—hide their money in tax havens. Among those elites are drug lords, who often turn to offshore banks to stash their illicit profits. What the papers also reveal, according to Carlsen, is how so little money is being spent on uncovering shady financial dealings, compared with the enormous amount spent on the fighting the drug war. But drugs continue to flow unabated because, she says, “There are some very, very powerful interests that want the drug war to continue because it doesn’t touch the business [side] and it creates this whole other arena of a war industry.”

There has been very little Western or English-language coverage of the caravan so far. Nor have many of the caravan’s core issues been raised during the U.S. primary election race. For politicians and the mainstream media, the war on drugs is an invisible backdrop hanging a little way south of our border. It began a long time ago and will continue only because ending the war would mean we were wrong all along or that we have given in to the power of the drug smugglers. And so it continues year after year, with millions of tax dollars spent and countless lives lost.

The caravan is heading to New York for the U.N. meeting to draw attention to the drug-related life-and-death issues that millions of Central and North Americans are facing. Sadly, the U.N. meeting, according to Carlsen, is focused on “whether they should reschedule marijuana or begin to open up legalization options.” She admitted that these are important parts of the solution, given that “it is the U.S.’ prohibition policies that have led to these militarized enforcement measures … that creates this huge repressive apparatus.” But, she says, what the U.N. is failing to acknowledge is that the “war on drugs is really a pretext for a war on us, a war on our families, a war on our movements.”

What caravan activists want at the U.N. special session is “to open up a dialogue and to create pressure from civil society which has the right to have a say in these issues,” said Carlsen. But the caravan also has deep symbolic value: to draw public attention to the many victims of the failed drug war and the devastating consequences in so many countries and communities. Two American participants, Laura Krasovitzky of the Drug Policy Alliance and Ted Lewis of Global Exchange, which coordinated the caravan, succinctly summarized its goal in The Huffington Post: “Twenty-two days, five countries, one message: end the drug war. If the people lead, the leaders will follow.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.