Mexico’s Runaway Train

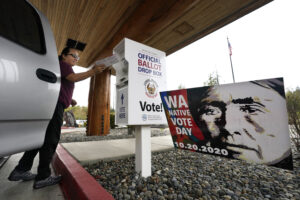

A rail line built for tourists may destroy Indigenous communities up and down the Yucatán peninsula. Construction of the third section of the Mayan Train project near Sudzal, Yucatan state, Mexico on December 19, 2022. The third section of the project will comprise a route of approximately 172 Km running from Calkiní (Campeche) – up to Izamal (Yucatan). The Maya Train project is one of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s flagship development projects. Its 1,525-km route will run through five states (Tabasco, Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo states), linking Maya temples like Palenque, Chichen Itzá and Calakmul, the colonial city of Mérida, beach resorts of Cancún, Playa del Carmen and Tulum and protected Sian Ka’an and Calakmul nature reserves. The construction began in June 2020 and has been awarded to private construction companies and the Mexican army. It is scheduled to be completed by 2024. Photograph by Bénédicte Desrus.

Construction of the third section of the Mayan Train project near Sudzal, Yucatan state, Mexico on December 19, 2022. The third section of the project will comprise a route of approximately 172 Km running from Calkiní (Campeche) – up to Izamal (Yucatan). The Maya Train project is one of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s flagship development projects. Its 1,525-km route will run through five states (Tabasco, Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo states), linking Maya temples like Palenque, Chichen Itzá and Calakmul, the colonial city of Mérida, beach resorts of Cancún, Playa del Carmen and Tulum and protected Sian Ka’an and Calakmul nature reserves. The construction began in June 2020 and has been awarded to private construction companies and the Mexican army. It is scheduled to be completed by 2024. Photograph by Bénédicte Desrus.

Breni Pacheco’s new neighbor is a drilling rig. It looks like a giant screw, several feet in diameter, twisting into the ground several yards from her home in Citilcúm, a village of cinder block houses situated in the Mexican state of Yucatán. Last December, the rig helped create a hole the size of a large swimming pool at the end of Pacheco’s once-quiet street. Another nearby construction site blocks the town’s primary roadway, diverting traffic around the community of 2,000. Within the village, local children have changed their routes to avoid the machinery and gaping holes in the ground, depriving Pacheco, a 25-year-old seamstress, of the extra income she earned selling candies and snacks to school kids on their way home.

The orange-vested men operating the drill are building the Maya Train, a 900-mile-long railway line expected to begin operating in December. Intended to bring cash-flush tourists from Cancún to other areas in the Yucatán peninsula — from Mérida in the west, to Chetumal in the south — it is the flagship development project of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. “There isn’t anything in the world like this train for its ecological, touristic, cultural and artistic importance,” said López Obrador in February. The previous summer, amid court challenges alleging the construction violated environmental protection laws, the Mexican president, known to the public as AMLO, declared the Maya Train a matter of “national security” to keep the bulldozers in operation. The government’s investment in the project since 2020 is fast approaching $20 billion.

When it opens in December 2023, the Tren Maya is expected to serve 8,000 tourists per day and generate an annual revenue of $150 million. Further millions are expected from businesses attached to the train stations, such as restaurants and hotels.

The Yucatán houses famous tourist hubs like Cancún, Playa del Carmen and Tulum, but remains one of Mexico’s least developed regions. Most Yucatecans outside resort cities still live traditionally in small villages where lanky street dogs are more common than tourists, and hammocks are often used as beds. Half of Yucatán state’s population identifies as Indigenous, and half of those people speak Maya languages in the home.

People living in the pueblos along the tracks have been promised new and more lucrative opportunities once the line opens. The government has promoted a vision of locals operating tours and selling wares to tourists. However, many of the region’s poorest towns are 45 minutes or more from the nearest train station, and most residents do not have access to a car. The price of gas alone could offset any profit from these new businesses.

Half of Yucatán state’s population identifies as Indigenous, and half of those people speak Maya languages in the home.

Among those without access to a vehicle is Breni Pacheco and her grandmother. Daily they sit side-by-side at identical sewing machine stations in their living room, working on embroidered linens to sell to neighbors. Although they live just two houses from the train tracks, it is a 20-minute drive from the nearest station where they might sell their garments to tourists.

“Right now, we’re only seeing the costs, none of the benefits,” Pacheco. “My cousins’ houses were destroyed to build the train, and the government bought them new houses, so they’re not homeless, but they lost the sentimental value of where they had lived for years.”

Numerous homes in Citilcúm have been demolished since construction began last fall. Their owners have been compensated with nearby plots, or homes in different towns estimated to have a similar value.

There was no negotiation involved in these decisions. Residents were simply told their houses would be seized. Those living directly under or beside a planned new highway overpass, meanwhile, have not been offered the opportunity to move. The town’s residents were not given the time or space to dispute or even discuss the construction with representatives at any level of government.

Carla Escoffié, a lawyer and activist representing Yucatán residents who oppose the Maya Train, says this is commonplace in the region.

“People have not received transparent information about the Tren Maya,” she said. “They are finding out about the plans and what the project will entail as the construction starts in their town. They think they can’t do anything.”

So far, more than 3,000 people have been displaced throughout the peninsula to build the train.

The government displaced hundreds of people from their homes during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, when figuring out a new living arrangement was especially dangerous. So far, more than 3,000 people have been displaced throughout the peninsula to build the train.

Many people living near the tracks are ambivalent about the project, seemingly unaware of how much their lives will be changed by the train. Concepción Caunvega, who lives in the town of Sudzal, 15 minutes from the nearest station in the city of Izamal, is skeptical that the train will negatively impact her life.

“I don’t know if it will be good or bad, but I think AMLO knows best,” she shrugged, standing in front of a poster of the Mexican president that hangs outside her front door.

* * *

Critics of the project argue the train will forever change the landscape of the Yucatán, a region rich in biodiversity and Indigenous history. They maintain that it will destroy invaluable ecosystems and Mayan ruins for the sake of profit, and turn the entire peninsula into a theme park for spring breakers. Escoffié says the damage to the region is already immeasurable and will only get worse as tourists flood into the peninsula, effectively Cancúnifying the area.

“Unfortunately, many of the effects of the Tren Maya aren’t yet visible, and most people are unaware of what the true effects will be,” she said.

The Yucatán peninsula is dotted with underground caves filled with clear pools, called cenotes, integral sites in Mayan religious practices, where artifacts, cave paintings and human remains dated to 12,000-years-ago have been found in recent years by cave divers and archeologists. So far, the Maya Train has put at least 6,000 cenotes, likely holding many thousands of artifacts and fossils, at risk of collapse under the weight of train cars and heavy machinery.

“The effects on the cenotes and the natural environment is something we’ll see after the train is already running,” Escoffié added.

So far, at least 25,000 ancient Mayan artifacts and ruins have been recovered from construction sites along the route of the train, including ancient homes, stone pots and sculptures. It remains unknown if artifacts and ruins have been destroyed due to the project, but prominent archeologists have begun to ask: If so many relics have already been found, how many were bulldozed?

It remains unknown if artifacts and ruins have been destroyed due to the project, but prominent archeologists have begun to ask: If so many relics have already been found, how many were bulldozed?

Escoffié notes that the characterization of Mayan culture represented in Cancún and other tourist areas present caricatures of the complex and varied collection of traditions and aesthetic styles that comprise Mayan culture. Her fear, shared by indigenous leaders and activists across the peninsula — is that the train will spread this caricature along the train line, eclipsing traditional aspects of Mayan lifestyle and customs in favor of cartoonish, Disney-style branding.

Guadalupe Gutiérrez Cáceres, director of the Colectivo Tres Barrios, a community group opposing the train in the state of Campeche, goes so far as to call the train a potential “cultural genocide” that threatens to destroy a way of life practiced in the region for millennia.

“This project is going to destroy what little is left of the Pueblo Maya, the way of life of the people who plant crops and sew seeds so we can eat delicious fruit and legumes. To promote this project, they’re destroying our customs and language. They want us to wipe the noses and clean the bathrooms of tourists. They’re not going to grant us dignified work.”

In 2021, Tres Barrios, representing 2,000 people across three Campeche neighborhoods, successfully negotiated with the government to reroute the train so it would not destroy any homes or displace anyone in their communities.

Nevertheless, the transformation of Campeche will still be immense, Gutiérrez Cáceres says. Unlike Mérida and Cancún, cities that are accustomed to tourism, she expects Campeche’s new industry will bring higher rates of violence to the city, as well as a potentially damaging nightlife scene.

In 2021, Tres Barrios, representing 2,000 people across three Campeche neighborhoods, successfully negotiated with the government to reroute the train so it would not destroy any homes or displace anyone in their communities.

“In Kalakmul, the region of Campeche with the most environmental destruction, the National Guard has come in. Now there’s more alcoholism, and the murder rate is higher,” she said. “In my neighborhood, someone was murdered last week with a pistol. We’re all asking, how did someone here get access to a firearm? Circumstances are already changing fast.”

In January, in Paraíso Nuevo, another town with its ribs at the tracks, police used physical force to remove families from their homes for demolition, so tracks could be laid. Residents of the town had blockaded construction since November 2022, placing felled trees across the highway to prevent trucks of cement and machinery from reaching the construction site.

A construction worker on Line 3 of the train, between Mérida and Cancun, who would not share his name, said he was unaware of any dissent or unrest. He thought most people were in favor of the train, and the only dissenting opinions came from environmentalists, who he thought were overreacting, and were not aware of the protocols used by engineers to protect the natural environment.

“A few of my friends are against it, but they’re environmentalist types and I don’t think they have the right information,” he said.

* * *

The segment of the train that runs through the lush jungle of southern Campeche, a protected natural environment, has already altered valuable ecosystems. Construction workers have cut down swaths of forests that are essential habitats for wild animals. On a visit to the area facing the starkest change, Gutiérrez Cáceres said she fought back tears watching machines fill a previously forested plot with concrete.

“The trees were cut down to stumps,” she said. “They say they have a plan to plant new trees, but where? This is the habitat for so many different species that rely on specific conditions for life.”

Gutiérrez Cáceres says that the government and its representatives have been dishonest about the train’s purpose of helping the local population. “The biggest lie they’ve told us is that this project will give us jobs,” she said.

She doubts that the train will bring economic opportunity and create jobs in Campeche, she explained, because most tourists will be more interested in visiting Mérida and the ruins at Chichen Itza. They will likely pass over Campeche, a territory featuring small villages, lesser archeological sites, miles of untouched jungle and only a mid-size city that is unaccustomed to tourism.

What the train will bring, says Escoffié, is National Guard troops and criminal organizations, who will battle over illicit activities throughout the course of the line.

Gutiérrez Cáceres says that the government and its representatives have been dishonest about the train’s purpose of helping the local population. “The biggest lie they’ve told us is that this project will give us jobs,” she said.

“Yucatán and Campeche are some of the safest states in the country, but Quintana Roo [where Cancun is located] is one of the most dangerous,” he said. “The touristic model attracts people looking to vacation, but it also attracts drug use and human trafficking.”

Gutiérrez Cáceres finds a dark irony in the fact that locals had been asking the government to build a train line in certain areas of the peninsula for years: an affordable mode of transportation that would make it easier for working people without cars to travel to other parts of the peninsula for work. The Maya Train is much more extensive than anything proposed by locals, but its 15 stations stop at only the biggest cities and touristic sites. Getting to the smaller and mid-sized towns where many locals might have found work still require a car.

“It’s not for us, it’s for tourists,” Gutiérrez Cáceres said. “It’s to present the culture like a circus. Mayan people will be made to perform their most important and private rituals and traditions like actors, like acrobats.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

According to Wikipedia, there was a referendum on the project:

The weekend of December 15–16, 2019, 92.3% of the people who participated in the consultation voted in favor, while 7.4% voted against the proposal.[9] 100,940 people voted,[10] 2.36% of the 3,536,000 registered voters in the 84 municipalities affected.

The referendum was criticized by the Human Rights Commission, but at least Obrador did put the issue to a vote. This would have been the time to...

According to Wikipedia, there was a referendum on the project:

The weekend of December 15–16, 2019, 92.3% of the people who participated in the consultation voted in favor, while 7.4% voted against the proposal.[9] 100,940 people voted,[10] 2.36% of the 3,536,000 registered voters in the 84 municipalities affected.

The referendum was criticized by the Human Rights Commission, but at least Obrador did put the issue to a vote. This would have been the time to organize effective opposition, not now after billions have been invested and the project is near completion. Mexico is heavily reliant on tourism -- the benefits may outweigh the costs.

hay un chingo de la corrupcion, incluso este Amlo, quien ha cambiado mucho...el tipe esta pedo con poder

the arguments against the loss of indigenous life are so ridiculous. The fact that village affected will have a train station 20 minutes away from their homes, is one of those silly arguments people use anywhere in the world when progress is arriving to a region.

...in any case, it is too early to say how much Yucatan people will benefit from a train that still is not running. I have visited the region and I trust the current president, so I believe the area will benefit from the increase of visitors

THE OIL THAT MEXICO EXPORTED CAME MOSTLY FROM THE SOUTH OF MEXICO and all Mexicans have benefited from it, The example the author gave of women having to change their selling habits because of the changes, are part of the modernization of any country. I am sure the article could have found other Yucatan families that are benefitting from jobs created by the train construction, but none were given. This sure looks like a HACK JOB against Mexico.