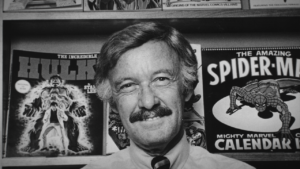

Burns’ Documentary Perpetuates the ‘Invisible Minority’

PBS documentarian Ken Burns has created a new series about World War II veterans but, according to the author, Burns left out some important contributors in his latest narrative: Latino and American Indian troops who fought for the U.S. (and are doing so now in Iraq and Afghanistan) and deserve due recognition.Frank O. Sotomayor Through the power of visual images and dramatic storytelling, a Ken Burns television documentary can become more powerful than a meticulous text about U.S. history. That’s exactly why a mini-war over his upcoming World War II series continues to flare.

War veterans, community groups and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus have protested that Burns’ upcoming PBS series does not feature a single Latino during the entire seven TV segments, totaling more than 800 minutes.

Citing a history of being excluded or marginalized, Latinos took their campaign to PBS, demanding that the TV epic be inclusive of historical fact.

After fielding months of complaints, PBS and Burns said they would include “added content” about Latinos in the programs. But that did not resolve the matter. Will the new material be incorporated in the main Burns documentary? Or will it end up as an appendage, an add-on meant to quiet an ethnic group flexing its new political muscle?

In a letter to PBS, the 21-member Congressional Hispanic Caucus said it was profoundly disappointed at the network’s plan and won’t support a decision that “ignores or segregates our soldiers, our heroes, or our history.”

An estimated half-million Latinos, fighting from Normandy Beach to Iwo Jima, helped the U.S. achieve victory over Hitler, Mussolini and Imperial Japan. Countless numbers died on the battlefield; researchers count 13 servicemen — 11 Mexican-Americans and two Puerto Ricans — who earned the Medal of Honor for heroism.

Some people will contend: “There they go again: Latinos playing the ethnic card.” But this controversy is not about political correctness; it is about historical correctness. It is about storytellers giving this nation the full story.

Burns’ production was six years in the making, but no one on his team or at PBS “flagged this problem of Latino exclusion,” according to the Defend the Honor Campaign, a coalition of Latino groups. One campaign leader, professor Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, directs the U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project at the University of Texas, which has conducted 550 interviews with veterans nationwide and could have helped to identify subjects for Burns to interview.

Burns’ initial reply to Latino critics was, in effect, “No way, José.” He never intended the documentary, Burns says, to be comprehensive of all American groups. Rather, focusing on Sacramento and three other U.S. cities, he said he wanted to tell “human stories.”

That’s fine, but Latino veterans have some extraordinary human stories too. And not only does the Burns series leave out Latinos, but also Native Americans, who possess a remarkable war record of their own.

At an April 17 meeting, campaign leaders were told by PBS that Latino material would be incorporated in a “seamless manner.” To Rivas-Rodriguez and others, that meant the documentary would be re-edited. But Burns later said the film is finished and will remain intact. “We’re not changing the film,” he told an interviewer. “Think of it [the added Latino content] as an amendment to the Constitution.”

The Constitution? Surely you jest, Ken.

The Defend the Honor Campaign and the Hispanic Caucus have asked PBS and Burns to end the game of semantics and come clean. Burns’ comments suggest the added Latino — and Native American — material, now assigned to Mexican-American filmmaker Hector Galan, may be shown at the end of each segment, just as viewers may be reaching for the remote.

The sense of being excluded from the mainstream of American life is not new for Mexican-Americans and other Latinos. Only a few decades ago, we were called the “invisible minority.” Now, clearly, that is changing, although Burns’ series renders us invisible once again.

Burns’ snub is particularly painful to Latino families with a tradition of military service. Today, you can’t go a block in East L.A. without finding a Latino family with a loved one risking his or her life in Afghanistan or Iraq.

The World War II experience was pivotal for Latinos, whose wartime experiences opened up opportunities. Yet, many returned to the Southwest to confront segregated swimming pools, schools and neighborhoods. Undeterred, they took jobs in industry and business and some earned college degrees via the GI Bill.

From that generation came not only mechanics and carpenters but also labor officials, community service workers and teachers. Those noble Latino soldiers of World War II — who did not get a single page in Tom Brokaw’s best seller — must be acknowledged as part of “the Greatest Generation.”

And Native American war veterans deserve recognition, of course, for their wartime contributions.

Because of Burns’ stature, his documentaries have the ring of the authentic last word. That’s why he bears a special responsibility, particularly when his films are to be aired by publicly supported PBS.

I am dumbfounded about how Burns, in today’s diverse society, could be so clueless. How could he omit such important elements of the WWII story?

I support artistic freedom and don’t endorse the idea of people in Congress trying to micromanage film content. So the ball is in Burns’ court: He should decide, of his own accord, to revise the main body of his documentary to incorporate Latinos’ and Native Americans’ war legacy. Their wartime contributions should be recognized in the main run of history, not as a footnote.

Sotomayor is associate director of USC Annenberg’s Institute for Justice and Journalism.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.