The First War On Protesters

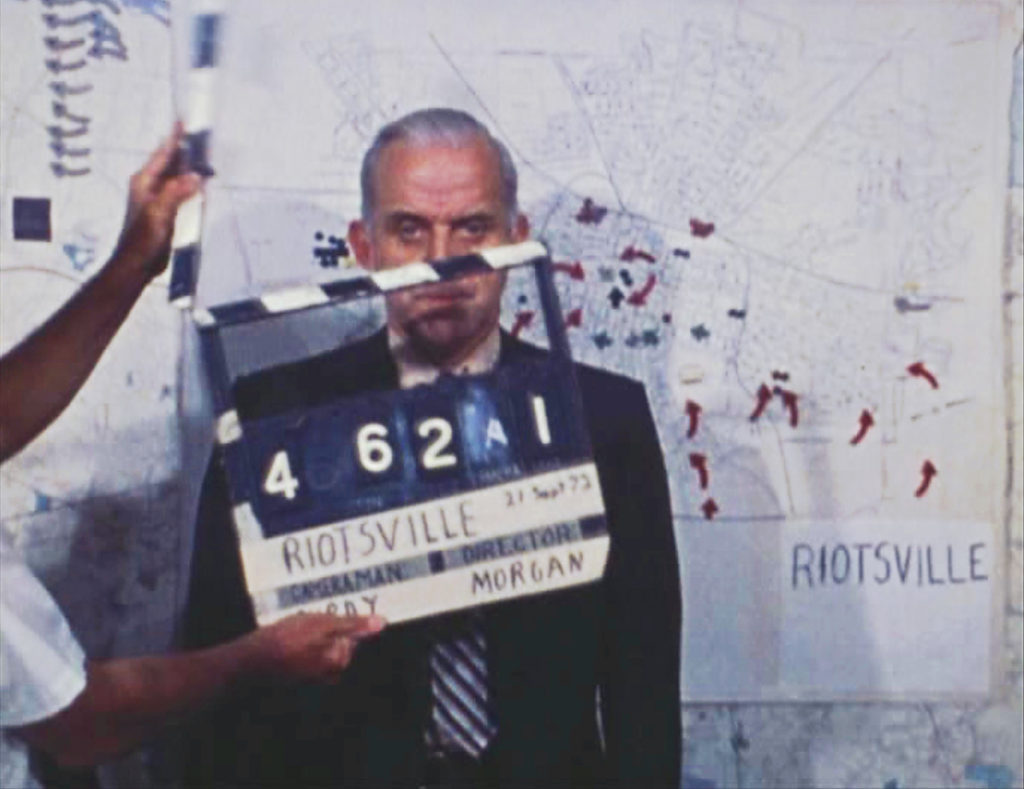

A new documentary examines the government’s Potemkin protests of the late 1960s. A scene from Sierra Pettengill's documentary film, "Riotsville, U.S.A."

A scene from Sierra Pettengill's documentary film, "Riotsville, U.S.A."

Riotsville, U.S.A.

Dir. by Sierra Pettengill

Composed entirely of footage from the late 1960s — both TV broadcasts and reels found in government archives — Riotsville, U.S.A. tells the story of two sham towns built by the U.S. military for the sole purpose of simulating the violent submission of political protest and urban riots. This eerie chapter of the late-middle 20th century helps us understand the militarized American state of the 21st, where police roll through city streets ready for war at the first sight of civil unrest — especially Black unrest — a throughline made explicit by the film’s director and primary researcher, Sierra Pettengill.

But despite the contemporary resonance of the film’s disquieting footage, much of it culled from unclassified archives in the public domain, Riotsville, U.S.A. seldom rises above feeling like an assemblage of historical footnotes. The expository voiceovers by actress Charlene Modeste and video essay stylizations clearly orient the viewer in the late ’60s, but never emotionally capture or convincingly explain the profound revolutionary spirit of that time, a zeitgeist of protest and awakening that so threatened the establishment, it spared no cost on rehearsing its suppression.

We learn from on-screen text that the Potemkin towns were inspired by the riots of the preceding years, such as the Watts Riots of ’65 and the Division Street Riots of ’66, which led President Lyndon Johnson to form the 1967 Kerner Commission to study the root causes of social unrest as the infamous “long, hot summer of 1967” was unfolding (the country would see upward of 150 race-related riots that June and July). The commission’s findings related to racial and economic inequities were mostly ignored, but as we learn from Modeste’s moody, philosophical voiceovers, the Kerner report helped hatch and guide the idea of constructing elaborate military-run re-enactments.

A dozen fake towns were constructed on Army bases for these exercises. The film centers on two in particular—both nicknamed “Riotsville”—built in Virginia’s Fort Belvoir and Georgia’s Fort Gordon in 1967. The faux storefronts featured generic business names like “Appliance Center” spelled in big block letters on façades resembling old movie sets, where the cowboy strolls into town and exacts righteous vengeance on an outlaw. The cowboy, in this case, is the American soldier but the outlaw rioters are also played by soldiers, who begin the cycles of violence without rhyme or reason. The organizers of these theoretical exercises cared little for backstory, or cause and effect. As bejeweled generals observe gleefully from nearby bleachers, the spectacle always begins and ends the same way: the rabble rousers turn violent, are suppressed, then locked up. Order is restored; authoritarian “justice” prevails.

Though Riotsville, U.S.A. offers fleeting clues about the era’s racial tensions, not enough is said about the origins of the remarkable spectacle of the state rehearsing the dehumanization of its people and bludgeoning them with batons.

The viewer is no closer to the action than the military brass overseeing it. Not just because much of the archival footage was shot from a distance, but because its act of witnessing — of using this footage to comment on the 1960s and today — is limited to the drills themselves, with little contrast or comparison to the real methodologies for which they served as early models. While text slug lines and inserted images provide hints of a larger story — the “Riotsvilles” at Belvoir and Gordon were built on military bases named after a plantation and a slaveholding Confederate general, respectively — the film offers no deeper scrutiny of the white supremacy embedded within American militarism, even while making cursory mention of the war in Vietnam. Focusing on the “what” of these simulations — fake looters are apprehended — the “why” is rarely approached with rigor or scrutiny. The rows of Potemkin storefronts are merely treated as a setting, much as they were by the rehearsing riflemen, leaving untouched more pressing questions raised by the U.S. government’s decision to bring counterinsurgency home.

At the time, the public may not have been aware of the re-enactments, but the aforementioned questions loomed large thanks to the real violence that occurred whenever the National Guard was called into rioting cities. These anxieties animated Peter Watkins’ 1971 mockumentary Punishment Park, a psychodrama that saw American dissenters turned into living targets for National Guard trainees. However, where Watkins’ film places the military’s dehumanization front and center, Pettengill’s leaves it in the margins.

Though Riotsville, U.S.A. offers fleeting clues about the era’s racial tensions, delivered through clips of televised interviews with Black preachers, not enough is said about the origins of the remarkable spectacle of the state rehearsing the dehumanization of its people and bludgeoning them with batons. Do these rehearsals pave the path for the real thing — does it make it easier for the soldiers? The Riotsville enactments are, in theory, fascinating windows into this question, but the film is too focused on the simulated images of brutality to ask how they connect to real-world equivalents that have become all too familiar in the age of the smartphone.

Which isn’t to say the film’s presentation of real violence is dulled. Its first cut from Riotsville to a real riot — in Washington D.C., after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. — deploys news footage of a shattered McDonald’s window, as if to subtly critique the journalistic gaze at the time, and its concern for capital and property above all else. (While not explicitly mentioned in the film, the Kerner report did, in fact, include a media critique in its findings). Modeste’s voiceover hints at scattered ideas about racial and economic inequalities, past and present, but they are just that: a smattering of possible deep approaches to the story, few of which are afforded room to breathe. Specific riots are referenced and given exact dates and locations, but rarely are their causes contextualized. Ironically, the film’s approach ends up not all that dissimilar from that of the U.S. military: it presents riots stripped of history and humanity.

The movie contains some admirable stylistic flourishes, such as Pettengill’s occasional application of digital slow-motion to old film footage, resulting in a morphing effect that creates overlapping, nonexistent “guess frames,” blending pretend rioters with their pretend surroundings, as if the very fabric of these images were being called into question. Some bits of information, presented via documents and other text, arrive in furious flurries of montage that grab you by the throat. At one point, the screen is consumed by extreme closeups of real rioters, printed in newspapers at the time; these are presented so closely that they appear as a series of dots, morphing into one another, creating a continuum of images and waves of rebellion. However, the frame never zooms out to capture the scope of these pictures, or what and whom they were really about, leaving the film’s connections between the real and fake unrest aesthetically persuasive. It is, perhaps accidentally, the most fitting metaphor for the movie itself, which hyperfocuses on a litany of issues, but seldom captures the bigger story of their radical entwinement, then and now.

The meticulousness of the Riotsville towns brings to mind recent works like Nathan Fielder’s HBO reality series The Rehearsal and Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s cinematic mega-project Dau, which involve large scale reconstructions and re-enactments. Both are extensions of their creators’ respective egos; the former scrutinizes this impulse, while the latter lets its creator’s abusive tendencies run rampant. Either way, the most fascinating element of both works is the relationship between creator and creation, and what these vast simulations have to say about the people running them. This element is sorely missed here, because while the Riotsville rehearsals are discomforting to watch, they aren’t nearly as unnerving as the idea of the U.S. government — the project’s “showrunner” — playing god with people’s lives. Riotsville, U.S.A., despite the rich material it had to work with, fails to capture the enormity of its implications.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.