Ava DuVernay’s ’13th’ Signals Beginning of a Mass Awakening for Black America

The 2016 documentary has given a voice to African-Americans, who now have more tools to fight for truth and justice.

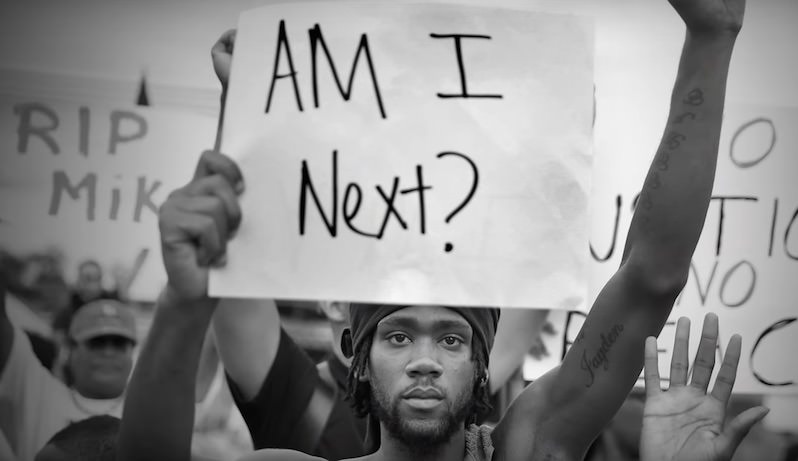

A scene from “13th,” which has been nominated for a 2017 Academy Award. (Netflix US & Canada / YouTube)

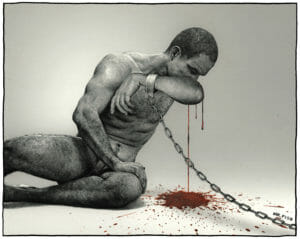

Today, there are more African-Americans incarcerated than were enslaved in the 1800s. The causes and enablers of this societal epidemic of mass incarceration are deeply rooted in systems of corporatization and consumerism. The widespread privatization of prisons has resulted in the manipulation of policy and lawmaking by private organizations that lobby Congress for the benefit of corporate sponsors. The scale and persistence of the issue speak to the relentless pursuit of human commodification for profit.

The acclaimed documentary “13th,” directed and produced by Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Ava DuVernay, unapologetically dives into the twisted systemic issue of mass incarceration and race. The film premiered on Netflix on Oct. 7, 2016, during the presidential debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, before the majority of African-Americans voted for Clinton in the 2016 election.

On Jan. 28, Blackwood Alliance and The California Endowment held a private screening and panel discussion of “13th” at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center in Los Angeles, in an effort to “create spaces for dialogues for films” in the age of President Trump, who, after only eight days in office, had already shaken up the country with a slew of executive orders, Cabinet nominations and threats that could impact African-Americans, as they feared after he was elected.

It was clear from the 100-plus (predominantly black) audience members at this film screening that a serious sense of urgency is bubbling up from within the African-American community. When scenes in the film showed former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Donald Trump, the crowd erupted in outrage. One gentleman stood up and shouted his frustrations and fears about our current political reality.

The passion was just as intense afterward, on the stage. A panel with DuVernay, Dr. Melina Abdullah, Cynthia McClain-Hill and Nipsey Hussle expressed their hopes for increased dialogue. “So often we industry people have our premieres and our screenings ‘up there,’ ” said DuVernay, referring to Hollywood elitism. “And even if it’s populated by black and brown people and women, it never really gets to actual community forums like this, or put together like this, where there’s a robust dialogue afterward. I think those connections are important.”

The documentary is spurring more calls to action. Watching it post-inauguration has prompted an increased interest in unraveling and understanding the political system among the African-American community. Because of its intensity and fearlessness in displaying racially motivated brutality—juxtaposing the 1960s Jim Crow era (images of black men being pushed and shoved because they attended integrated schools, black women being yelled at by white women as they enter a newly integrated store) with Trump protests of today, and audio clips from the politicians and government officials clearly defining racist agendas (such as Richard Nixon’s aide John Ehrlichman admitting that the United States’ war on drugs was meant to target blacks) —“13th” has stimulated black America in a quest for truth.

DuVernay believes this passion is the beginning of a wave of more black educational films providing a platform for self-reflection and political expression. She noted box-office numbers for “Human Figures” and “Fences,” where people of color play the lead roles. “13th” is now available on Netflix in 190 different countries. The effort to create a mass awakening of the systems of oppression, truths in black history and reclaiming the humanity of black lives through films such as “13th” can enlighten and shake up the collective consciousness of those who watch them.

Critics have often identified the problem of black and brown liberation as one of subservience and lack of discernment—referring to the inability to peel through the rhetoric and lip service of liberal and Democratic leaders who capture the black vote. Meanwhile, the same leaders are beholden to corporations and establishments that perpetuate the issues they are complaining about: the prison-industrial complex, school-to-prison pipeline, welfare systems, privatization of prisons and mass incarceration. “Now we have a president who is, I don’t think, doing anything really new, and I think that’s why it’s really important to know our history,” DuVernay said. “He’s just being louder about it and talking about it on Twitter.”

During the 1964 presidential election, Malcolm X had similar attitudes toward Barry Goldwater as DuVernay does toward Trump:

Well, if Goldwater ever becomes president, one thing his presence in the White House will do, it will make black people in America have to face up to the facts for the first time in many, many years. This, in itself, is good in that Goldwater is a man who is not capable of hiding his racist tendencies, and at the same, he’s not even capable of pretending to Negros that he’s their friend. So this will have the tendency to make the Negro, probably for the first time, do something to stand on his own feet and solve his own problems instead of putting himself in a position to be misled, misused, exploited by the whites who pose as liberals only for the purpose of getting the support of the Negro. So in one sense Goldwater’s coming in will awaken the Negro and will probably awaken the entire world more so than the world has been awakened since Hitler.

Films like “13th”—which refers to the 13th Amendment and how slavery still persists in America’s criminal justice system—are important because they lift the veil of what we’ve been conditioned to believe through “patriotic” propaganda, “bleached” versions of history taught in schools, lack of transparency and the ultimate quest for control and power. These issues bring into question who and what are the real threats to the issues plaguing the African-American community.

McClain-Hill, an attorney and public policy strategist who became a member of the Los Angeles Police Commission in 2016, spoke about the film from the lens of 20-plus years of experience working the political system. “It underscores how critically important it is for us to see these issues not just at one level, not just at a level of combat with police in the street, but to understand it from the perspective of government and how it works and who it benefits and all the employers of the system,” McClain-Hill said.

When asked what she wanted the audience to do after watching the film, DuVernay responded, “It’s a deeply layered, systemic, generations old, insidious disease that is not going to be fixed with Band-Aids and surgery. So what part can you play?”

A mass awakening has begun. Black America has more tools, access and influence than ever before. Documentaries, protest movements and social media haven given voices and legitimacy to those otherwise forgotten. “The film gave a vocabulary to what we felt,” said Nipsey Hussle, a rapper and business mogul from South Los Angeles known for his 2016 single with YG titled “FDT (Fuck Donald Trump).” The working class has been given a platform through art forms such as DuVernay’s work and will remain as long as black oppression continues. The truth about manipulative systems will be exposed and history retold to include lost stories.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.