Allen Barra on Cornelius Vanderbilt

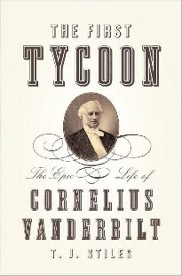

A new and outrageously entertaining biography of America's first tycoon by T.J. Stiles, one of our best younger historians, sheds new light on the monumental life of what Stiles rightly calls "an instinctive predator" and his mixed and enduring legacy.

A one-time friend of Cornelius Vanderbilt famously said upon the great man’s death, “He died without making a bad debt or leaving a friend.” Like so much said about Vanderbilt, the statement contains a hard kernel of truth. “The Commodore” — he got the nickname by dominating early steamboat transportation between New York and New England — did make the occasional bad debt, along with a great many enemies, few of whom actually knew him personally, and at least a few friends. Mark Twain even more famously wrote in an open letter, “You observe that I don’t say anything about your soul, Vanderbilt. It is because I have evidence that you haven’t any.”

But as T.J. Stiles makes clear in his monumental and outrageously entertaining biography, “The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt,” Cornelius may not have had a soul but he had a pretty stout heart, and he made a few friends in his lifetime — though some of them would be better classified as admirers. And he even “rather liked his enemies. For decades, he had deftly switched from enmity to friendship, embracing … [several of them] once their wars ended. He never took business disputes personally.” (Making an exception, Stiles points out, for such post-Civil War robber barons as Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, men who, in Vanderbilt’s estimation, “broke the gentleman’s code of business combat.”)

It was business, not personal, and it was combat, and the greatest financial warrior of his kind, in American and perhaps all of world history, was Vanderbilt. Unlike most of the great 19th century tycoons who followed in his wake, though, Vanderbilt left something tangible behind — a legacy that, for reasons both good and bad, continues to influence this country. Without pulling any punches — Stiles is very clear that Vanderbilt was “an instinctive predator” – “The First Tycoon” makes a solid case that most of what he accomplished was for the good, or at least did more good than harm.

Born to a sturdy Dutch father and English mother in 1794, Cornele, as his mother called him, began his business career in a New York City that “stank.” The docks consisted of solid masses of stone and dirt packed into wooden cribs, creating enclosures called slips. The water within the slips, observed a traveler, “being completely out of the current of the stream or tide, are little else than stagnant receptacles of city filth; while at the top of the wharves exhibits one continuous mass of clotted nuisance, composed of dust, tea, oil, molasses … where revel countless swarms of offensive flies.” It was a second-rate city when compared to Philadelphia, but, as one observer put it, “Every thought, word, look, and action of the multitude seemed to be absorbed by commerce.” Everything “was in motion; all was life, bustle and activity.” Thanks largely to the bustle and activity of a handful of men, most notably Cornelius Vanderbilt, New York would soon vault into the position of the commercial center of the New World.

The thrift inculcated by Vanderbilt’s parents helped breed genius. “His life,” wrote a contemporary admirer, “was regulated by self-imposed rules.” He lived and worked “with a fixedness of purpose as invariable as the sun in its circuit. Among other things, he determined to spend less every week than he earned.” He told the New York Tribune in 1855, “The share of prosperity which has fallen to my lot is the direct result of unfettered trade and unrestrained competition.” In our own time, a great many executives who receive millions for failing sing the praises of free trade while forgetting the part about need for competition.

Stiles writes in a style the Commodore would have appreciated: swift, economical and direct, daring but never hyperbolic. The nearly 600 pages of text seem to fly through your hands. Judging from his previous book, “Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War” (2002), and now “The First Tycoon,” Stiles has a genuine gift for putting complex historical subjects into perspective without lapsing into revisionism. In “Jesse James,” he was able to demonstrate that his subject had more in common with a modern terrorist like Osama bin Laden than with Old West outlaws like Billy the Kid without seeming trendy. Given the current state of the economy and those who are primarily responsible, it would have been easy for Stiles to cater to current biases and write Vanderbilt off as the father of the modern corporation — which of course he was — leaving it for readers to take that as an automatic association with evil.Instead, Stiles takes a much more daring approach and presents Vanderbilt as a hero, not a hero as in a Hollywood film or even the cartoonish Ayn Rand type, but more like a classic figure with all of his virtues and flaws rendered in sharp relief. Here was a man who, in building his steamship trade, “had acted like a Viking prince, taking his fleet wherever trade or plunder seemed most promising, freely abandoning markets for a price.” At the same time, “There was something Homeric in this uneducated man’s conception of himself. … Like Odysseus he would face ocean storms, river rapids, tropical fevers, and the crocodiles and sharks of Nicaragua’s waters. These trips would further open his eyes to the world and enhance his heroic reputation.” And if he was a tyrant, “at least he made the trains run on time — and profitably.”

This Viking/Greek sailor put a uniquely American tinge to the notion of great wealth: he was no member of “an affected aristocracy, the patricians of puffery.” To Jacksonian Democrats, writes Stiles, “who championed laissez-faire as an egalitarian creed, he had epitomized the entrepreneur as champion of the people, the businessman as revolutionary.”

The pseudo-brokers in the movie “The Boiler Room” would better have stopped watching scenes from “Wall Street” and read “The First Tycoon”: “When I have some money,” Vanderbilt once said, “I buy railroad stock or something else. But I don’t buy on credit. I pay for what I get. People who live too much on credit generally get brought up with a round turn in the long run. The Wall street averages ruin many a man there, and is like faro.” Tell us about it, Commodore.

In perhaps his most significant accomplishment in “The First Tycoon,” Stiles celebrates Vanderbilt’s colossal achievements without succumbing to the Commodore’s spell: “With the wave of one hand he created tens of millions in new wealth; with a wave of the other, he crushed his enemies; with cold-eyed calculation, he gambled with the lives of millions. The American people were fortunate that he gambled so well, but they had no say in how he placed his bets. Black Friday posed a great question: What was the place of a railroad king in a democracy of equals?”

It’s a question that hasn’t been answered 132 years after his death, but there should be no confusion of the issues. The ways in which Cornelius Vanderbilt created enormous wealth helped create enormous wealth for an entire country. He helped make New York into the city we have come to know and spurred San Francisco into a major city by providing tens of thousands with the transportation to get there after the California gold rush in 1849. He was the major impetus behind the most important business of the 19th century — railroads — and by ferrying so many future Californians to Panama, he can be regarded the grandfather of the Panama Canal.

In short, as Stiles puts it, “Probably no other individual made an equal impact over such an extended period on America’s economy and society. Over the course of his 66-year career, he stood on the forefront of change, a modernizer from beginning to end. He vastly improved and expanded the nation’s transportation infrastructure, contributing to a transformation of the very geography of the United States.”

His fortune was nearly incalculable; by the time of his death in 1877, “virtually every American had paid tribute to his treasure.” His power was immeasurable. (A statement falsely attributed to him by the popular early 20th century historian Matthew Josephson — “What do I care about the law? Hain’t I got the power?” — was nonetheless accurate.)

Given that wealth and power, Vanderbilt could easily have been a madman or the soulless despot that Mark Twain thought him to be. What’s amazing is the degree to which his fortune seemed to sober him. He made and played by his own rules — “the gentleman’s code of business combat.” Vanderbilt did not believe in the creation of wealth by simply rearranging numbers on paper or manipulating Wall Street. To the greatest capitalist the world has ever seen, unfettered trade and unrestrained competition never meant a world without rules.

|

Allen Barra is a contributing editor to American Heritage and writes about sports and the arts for The Wall Street Journal. His latest book is “Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee,” just released by W.W. Norton. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.