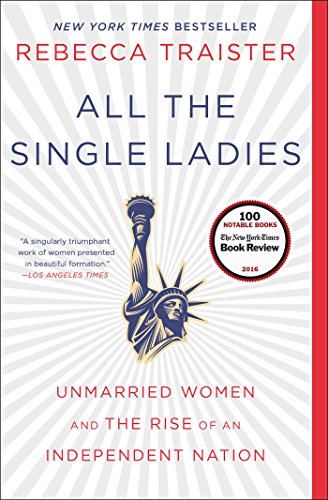

All the Single Ladies

Rebecca Traister excavates the economic, social and sexual options women have had historically in relation to marriage, and tracks how the growing numbers of unmarried women have advanced the fights for abolition, suffrage and labor rights. Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster

“All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation” A book by Rebecca Traister To see long excerpts from “All the Single Ladies” at Google Books, click here.

In “All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation,” author Rebecca Traister excavates the economic, social and sexual options women have had historically in relation to marriage and sees a brightening future for those who postpone it or avoid the institution altogether. She also reveals that, with the exception of short-lived phases, the numbers of unmarried women have been rising since the end of the 19th century, and tracks how this demographic shift grew out of and advanced the fights for emancipation from slavery, labor rights and suffrage.

Traister packs in a broad mix, perhaps too much so, of academic, cultural and anecdotal evidence to support her book’s fair-minded approach and positive theses. Connecting her own coming-of-age to events covered, such as the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill debacle where she starts, Traister discusses political and cultural low points that raised awareness of the ways women’s rights are insignificant to those in power. Early chapters maintain a conversational style, even with the numerous historical and sociological references. And there are many fascinating facts and supported theories about the ways women’s growing freedoms actually increased liberty and justice for all. As Traister puts it:

Over a century in which women had exercised increasing independence, living more singly in the world than ever before, the movements that independent women had helped to power had resulted in the passage of the 14th, 15th, 18th, and 19th Amendments to the Constitution.

They had reshaped the nation.

Despite such a protracted “beginning” of the long and trammeled road to equal footing with men — still unattained — these auspicious outcomes are stirring.

Many contemporary interviews with women of all ages are included, and Traister shares her experiences as a young adult in New York, making friends and finding her professional footing. Some interviewee stories are more captivating than others, and occasionally the book reads as a series of girls’ almost-growing-up stories. Like a thought Traister noted regarding her own reading of “Goodbye to All That,” Joan Didion’s farewell to New York, I too “felt not an iota of recognition” as I read some of these tales. Our times become dated so quickly. (Even so, few nonfiction works have sparked so much reflection on and comparison to my personal experiences as “All the Single Ladies” has.)

And Traister is adept at animating her life’s key moments and emotions. There’s also a lovely passage about her grandmother Eleanor’s stoic attempt to comport with the domestic confines of her time, relieved by an opportunity to return to her beloved science classroom. That pinch-hitting chance turned into a 22-year run. Spoiler alert: Eleanor regained professional satisfaction and her husband and family survived!

A section on the historic role of cities and their infrastructures in women’s advancements is particularly interesting. Because of the jobs provided by cities as industrialization took off, many women moved to urban centers. There they found not only wages, but freedom from father and family; also companionship, entertainment, and domestic structure, and those advantages continued throughout modern times. (Though I never felt domestically structured dragging my laundry in Manhattan to the laundromat and back.) And while life was extremely trying for women of color in early 20th century New York, this moving excerpt of Elise McDougald’s 1925 essay, “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation,” describes the draw of Harlem for her:

…more than anywhere else, the Negro woman is free from the cruder handicaps and the grosser forms of sex and race subjugation. Here she has considerable opportunity to measure her powers in the intellectual and industrial fields of the great city.

In this book covering so many realms related to unmarried women, Traister handles the subject of sex — with and without emotional attachments — sensitively. It’s a complex one, and opinions about it are often telling of one’s age, politics and fears. Traister reports the facts and findings of reasonable, varied studies and attitudes on these issues. What’s brushed by, though, is the related subject of hyper-sexualized imagery in entertainment and advertising that bombards — and affects — everyone, but which is centered on the objectification of girls and women. Movies and advertising have long favored “hot” rather than strong females, in vulnerable poses and attire, and the volume and impact has increased in recent decades. Then there’s the ballooned wedding market, also cultivated through media, which Traister mentions. Difficult as it may be to grapple with the contradictions and connections among these arenas, they are powerfully linked to young women’s expectations and pressures, mores and marriage, and therefore worthy of deeper inquiry and analysis. Fewer personal anecdotes about social responses to being single, which do not become more illuminating with repetition, would have made room for this discussion.Traister is an optimist through and through, and hope emanates from every chapter. However, because of her expansive, diverse research, and concessions to the limits of marriage as a divining rod of progress, as much bad as good news for America fills the book’s pages.

Our country is millennia ahead of the numerous global locales where control of women is cruel, violent and common, and no unmarried young woman is deemed respectable.

But, Traister notes:

…while some women are enjoying more educational, professional, sexual and social freedom than ever before, many more of them are struggling, living in a world marked by inequity, disadvantage, discrimination and poverty.

It’s crucial to unpack what’s true and what’s not true about female advancement — and single female advancement — across classes, rich, poor, and in between. When it comes to female liberty and opportunity, history sets an extremely low bar.

Traister’s writing becomes more gutsy and impassioned (and mindful of earlier work) in the chapter focusing on injustices experienced by poor women, many nonwhite, doing unskilled low-paid labor. And while reading statistics is often a dry experience, she integrates them effectively. Such as:

…in 2014, the median wealth, defined as the total value of one’s assets minus one’s debts, of single black women is $100; for single Latina women it is $120; those figures are compared to $41,500 for single white women. And for married white couples? A startling $167,500.

Is your hair on fire?

Even the strides of privileged educated women cannot compare statistically to those a white man can make in business and powerful institutions. It’s not a tiny bit close. If success is the best revenge, women remain far in arrears.

As motherhood continues to be an economic barrier for most women, Traister explains how poverty and motherhood became racialized in America. She joins authors such as Michelle Alexander, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Ian Haney Lopez in calling attention to the institutionalized limits on the ability of nonwhites to gain full entry to the economy, and to accumulate even modest wealth. She revisits the inaccurate conclusions of Moynihan’s 1960’s-era report that morphed into an oft-repeated meme about black morality and culture as the culprits of poverty. The lineup of conservative politicians and think tank professionals still hawking the unproven theory that marriage — early marriage, at that — is the magic potion for poverty relief would be comical if it were not so successful in recruiting more of those who are threatened by female autonomy.

As with most policies and attitudes regarding women’s rights over reproduction, the fear factor is currency for control. And with Fox News and the internet, misinformation continues its hit runs throughout ill-educated, screen-addicted America. If only this would go viral:

Maddeningly, having children enhances men’s professional standing and has the opposite impact on women’s. [From a 2014 study, using data from 1979-2006, sociologist Michelle Budgie found] …on average, men saw a six percent increase in earnings after becoming fathers; in contrast, women’s wages decreased four percent for every child.

Maddening, yes — it’s enough to keep one’s hair on fire. And it’s maddening how much men have to say about women’s bodies, childbearing and child-rearing, especially considering that “86% of Gen X and Baby Boomer men admitted in a Harvard Business School study that their wives did most of the child care.”

Traister incorporates current facts like these that slow down the parade of positive change, which is her main focus. These speed bumps of perspective range from the personal to the professional and political, and they admirably underscore her awareness, fair journalistic aims and concerns for all races and classes of women. But Traister tends to U-turn back to the upside after most cautionary asides. One might conclude that this is just the default position of an inveterate optimist — and who wants to read books filled with despair, anyway?

In 2016, however, it’s fair to say that after so long, the bumps are the bigger story, or at least the “big picture” story — and not just for women, for everyone.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.