A Whoremonger’s Tumble Into Love

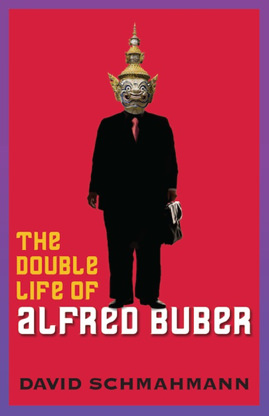

David Schmahmann, in the era of Spitzer, Edwards, Weiner and Schwarzenegger, has written a novel about a powerful man who risks his reputation and career for illicit sex and ends up in an unlikely relationship with a Bangkok bar girl. “The Double Life of Alfred Buber” may in some ways feel like a mystery novel, but it’s much more than that.David Schmahmann’s “The Double Life of Alfred Buber” takes the reader inside the mind of a man with a big secret.

An excerpt from the book was published on Truthdig here.

Alfred Buber, by his own account, is not an attractive man. Bald, portly, pasty, middle-aged, women pass him on the street without a second glance. He is also wealthy and successful, a partner in a white-shoe law firm. His British accent lends him a certain charm; his well-tailored clothes give him bearing and dignity. But these attributes, mostly superficial and hard-won, are not meant to make him marriage material. “I pack myself into my clothing so as to appear wholly complete, to lack nothing, to be beyond need,” he says. It is his goal to go unnoticed and to discourage prying, because he has a secret to protect. Alfred Buber, pillar of his community, is a whoremonger. Not just any whoremonger, but the most predictable and loathsome sort. This john has fallen in love with his prostitute. And he has made it his mission to save her.

As the story opens, Buber has just brought his paid-for ladylove back to his elegant manor on the outskirts of Boston. Nok is a dirt-poor country girl from Southeast Asia, sold into prostitution in a Bangkok bar. As she wanders through his house, he watches her take it all in—the Moorish arches, the art nouveau chairs, the white marble tub carved from a single block of stone. Through her eyes, he sees the life he has created for himself, and he holds his breath as he awaits her verdict. “Where are the people?” she finally says. “Only you here.” With that simple observation, Buber realizes that she sees, not his success, but the depths of his loneliness. In Buber’s own words, “Loneliness in men, after all, tends to acquire a sexual tinge, does it not?”

Author David Schmahmann could have easily written a story about a powerful man who, led by his libido, risks his reputation for some quick-and-dirty sex. In the era of Spitzer, Weiner and Schwarzenegger, it would have seemed to be ripped from the headlines. It would have mined similar socioeconomic territory: money and power buying youth and beauty. Like these recent political scandals, it would have raised the same question: What is in the psychological makeup of these men that compels them to court such risk?

But unlike the tales of Spitzer et al., “The Double Life of Alfred Buber” is a love story, and a sweet, often uncomfortable one at that. And unlike the American public, Schmahmann has little interest in the prurient details. In Buber’s world, even the most sordid transactions are recounted in a way that can best be described as “prim.” Instead, the author chooses to mine ickier, more uncharted territory, writing about the emotional emptiness that moves Buber to pursue this relationship. His deepest desires are more raw than anything that could be found on a whorehouse menu, and they can never be fulfilled with money.

“The Double Life of Alfred Buber” is a story about the power of secrets. He has accepted his need to pay for sex. For the successful but not-so-handsome businessman, he understands it as a practical exchange. He also understands the need for subterfuge. Before he leaves for vacation, he spends hours studying Paris travel guides. He reads up on museums and monuments, cross-referencing them with the list of must-sees that his boss’ wife has thoughtfully prepared for him. Of course he has no intention of strolling along the Seine; he’s going whoring in the squalid back alleys of Southeast Asia. He is appropriately scandalized by his own behavior, and he imagines the reactions of the people back home. What would his boss say if he knew? What would his secretary think? His mother? He pictures his Uncle Nigel’s “unique brand of scorn: ‘A sorry sight, indeed,’ he imagines him saying, ‘schlepping oneself across the world in search of desperate women. Is it more than that, Alfred? Could it ever be?’ ”

But as Buber obsesses over their imagined criticism, we begin to sense that he’s not merely flagellating himself by proxy. He is a man who is savoring his sins, even as he strives to conceal them. Anyone who’s ever behaved duplicitously—in other words, pretty much everyone—knows the smug satisfaction of it. You think you know me, but you have no idea. With this secret, Alfred Buber is no longer the mild-mannered milquetoast; he is a globe-trotting connoisseur of flesh, jaded and debauched. As he becomes more daring in his deceptions—now claiming Turkey for his phony destination—we see how much he loves his lies. He is not just shocked by his secret, he is energized by it. His double life has reached its tipping point: He enjoys paying for sex, yes, but it is overshadowed by the exhilaration of living a lie.

And then he falls in love. On one of his trips to Bangkok, he finds himself in a place called the Star of Love Bar. It is a dark, dank saloon where middle-aged foreigners are openly serviced by an array of impossibly beautiful, but equally dispirited, teenage girls. It is there that Buber meets Nok. She is sweet and studious, businesslike and acquiescent, and he is instantly smitten. They begin a romance beset by challenges—the language barrier, the cultural divide and, of course, the fact that Buber can never be certain that his feelings are reciprocated. He is keenly aware of the transactional nature of their relationship; he is sickened by the cliché. “Disgusting men,” he thinks, “so smug in taking what they are not entitled to have, in possessing what should not be theirs to possess, a disgrace to us all, these aging monsters and the lithe, giggling, animated things on their arms. They cling, look up appreciatively, have smooth legs, honey-colored legs that clip along like colts, crimped little waists, delicate shoulders.” Then Buber slips back into first-person narration, adding, “You see, I don’t need to be punished for my transgressions. I do an adequate job of it myself.” He knows he might be getting hustled, but he does not really mind. If it turns out to be real, he reasons, it will all be worth it. When he returns home, he starts sending her money, with the understanding that she quit the bar and go to school. He makes another journey, this time to the impoverished backcountry, to ask her father for her hand in marriage. But to his dismay, what would normally be a romantic gesture is no more than a business deal. For $500, he becomes Nok’s husband, guardian and owner. He goes back to New England to prepare for her arrival, and begins a new round of delicious hand-wringing. He imagines the scandal to come. What will the townspeople think? The moment they see him and Nok together, they will know exactly what is going on, who he really is. He realizes, then, that if he wants to have his whore and his reputation too, he must lock her away, keep her separated from the rest of his life.

Such is the alienating power of a secret, and alienation is something that Buber knows well. Born in England, raised in colonial Rhodesia, shunted off to America to avoid the draft, Buber never quite feels at home. He’s built himself a mansion, and it’s perfect, but it’s cold. Its luxury and largeness only underscore his loneliness. His lies have created a barrier between himself and others; with so much that he cannot say, how can he possibly connect? What’s worse, he’s become an observer in his own double life, watching both his respectable and debauched selves through the eyes of his co-workers, his family, his housekeeper, his whore.

It seems fitting that he would look to Nok for salvation. If his most forbidden wish is to inhabit his own life, who better than a prostitute—a penetration professional—to help him break through? He marvels at her ability to be intimate, yet remain separate. “I walk across to her and kiss her and of course she yields, kisses me back, and it is surprising to be confronted so immediately with the intimacy of a stranger. There is something peppery to it, something minty, a touch of sourness. … I lose my heart to her in this instant, to her earnestness, her generosity, her presence. … The part of her that has been most freely surrendered to a host of other men is all she yields. She gestures, leads, shows what I am expected to do, how I am to be serviced, is wary, quiet, almost, one could say, uninvolved. I possess her but it feels that I am in her debt, liable at any moment to feel her disengage, to lose something I never had in the first place. She is there, but she is not there. In short, she submits so entirely that it is as if she is not there at all.”

At times, Schmahmann’s book feels like a mystery novel, and that last sentence is a valuable clue. Is Nok even there at all? As the story unfolds, and Buber unravels, we begin to see that things are not exactly as they appear. In the opening pages, the book reads like a diary; as it progresses, we come to understand that it is a letter. To whom he is writing and why are two things that are not revealed until much later. By then, the only thing we know for sure is that Buber, as narrator, is not to be trusted.

In this fictionalized memoir, the term “double life” has a double meaning. Buber’s double life isn’t just the difference between what he does and what others think he does. There’s also a difference between what he does and what he only fantasizes about doing. It’s a neat trick of language, and Schmahmann deftly pulls it off. He uses verb tenses like a well-oiled time machine, moving seamlessly through Buber’s past, present and future. He bends reality by gliding between indicative and subjunctive moods, blending hard facts—“I was born in Africa”—with things that he might like to do or have done, such as flirting with a co-worker or taking Nok on a ski trip.

If it becomes difficult to distinguish Buber’s fantasies from fact, it also becomes evident that that’s Schmahmann’s intention. It would be impossible to go back and untangle the web, and even if it could be done, it would do the book a disservice. Through Buber’s deceptions, he reveals the truth about human need and frailty, and this truth is so precious—to quote Churchill—that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies. It’s really best to just go with it. Buber may fantasize and deceive, but his story doesn’t disappoint. In the end, Schmahmann has created an unforgettable character whose double life is as outrageous, and as familiar, as one’s own.

Robin Shamburg is the author of “Mistress Ruby Ties It Together: A Dominatrix Takes on Sex, Power, and the Secret Lives of Upstanding Citizens.” She is finishing her second book, “Dungeon Confidential.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.