The Stark Contradictions of Downtown Los Angeles

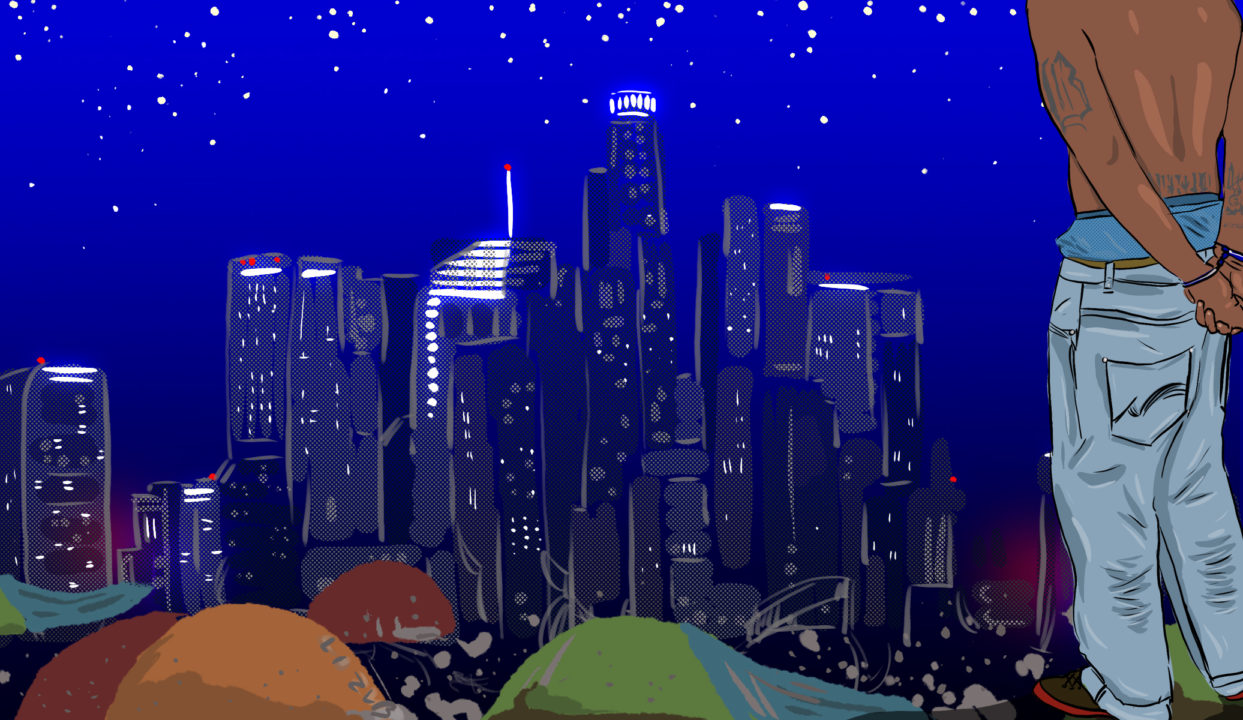

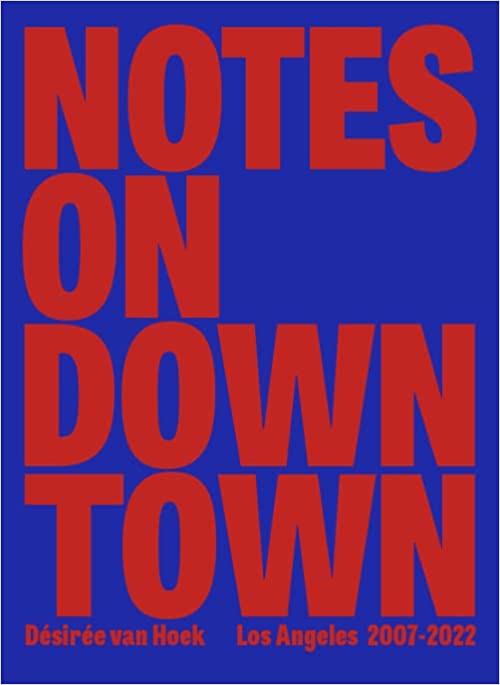

A Review of "Notes on Downtown" by writer, photographer and editor Désirée van Hoek. Downtown Los Angeles. Illustration by Elizabeth Von Blum.

Downtown Los Angeles. Illustration by Elizabeth Von Blum.

The following is a review of “Notes on Downtown” by writer, photographer and editor Désirée van Hoek, published in April 2022.

Los Angeles is a city of the most striking –– and often egregious –– paradoxes and contradictions. Often exciting, exhilarating and creative, it is a world center of art, culture and education. Its artists, musicians, literary figures, journalists, scholars, actors and filmmakers, architects, museums, colleges, universities, hospitals and many other professions and institutions rank among the finest ever. The city regularly produces progressive politicians and policies and many of its neighborhoods boast of their extremely comfortable standards of living.

At the same time, it’s a city — and an entire region — beset with poverty, inequality, racism, police misconduct, homelessness and massive human despair. No district better exemplifies those contradictions more strikingly than Downtown.

Simultaneously attracting artists and offbeat individuals looking to live unique non-mainstream lives, it also attracts affluent residents, some from the entertainment industry, others from new tech industries and real estate speculators of the professional/managerial class.

But Downtown is also the home of thousands of desperate souls who exist marginally in tents and other makeshift shelters, as well as migrants, many of whom lack proper documentation, from Mexico, Central America and other regions where turmoil and violence rule the day. Now, in early 2023, LA’s new progressive mayor, Karen Bass, has unveiled an ambitious plan to address the massive homeless problem. One hopes that she will be successful, but like many others on the Left, I fear that the problem may be intractable, absent structural change in capitalism’s grotesque divide among wealth and power.

Dutch photographer Désirée van Hoek has documented these striking contradictions of Downtown Los Angeles in her engaging yet disconcerting new book, “Notes on Downtown.” Van Hoek, who has worked in Downtown LA for several years, with a special focus on homeless people, has recorded the changes in the district in over 200 images. The book also contains incisive interviews as it documents the changing face of this area. Its skyscrapers, world-class museum and galleries, and pricey and stylish restaurants and bars and expensive condos now coexist uneasily with its longtime poor and mostly Latino/a residents and older shops and businesses.

Many of these changes are dramatic and glitzy, reflective of the region’s increasing gentrification. They contribute to the city’s status as a major world capital, the site of international travel, especially with the waning of the pandemic and the locus of the 2028 Olympic games. Van Hoek’s photographs reflecting these changes are impressive. Like the finest social documentary photographers, her strength lies in her vision, her capacity to see and express the deeper human realities and their dismal living conditions that exist beneath the surface. Perhaps her status as a foreigner, ironically, affords her a unique opportunity to understand the plight of marginalized Americans, particularly in Downtown Los Angeles.

Few could deny the vibrancy of Disney Hall (Figure 1), the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Broad Museum (even for those critical of its architecture). Unquestionably, each of these institutions has attracted thousands of visitors and contributed to LA’s global stature. Moreover, the treasures within them, from first-class musical performances to magnificent visual artworks, and much more, solidifies the city’s reputation. Van Hoek’s photos of high-rises and skyscrapers (Figure 2), previously prohibited by zoning regulations, uses the power of visual art to make this point persuasively and reveals how Downtown has joined other world center cities as a multifaceted cultural and commercial hub.

But all of that, finally, is superficial. “Notes on Downtown” at its core focuses on the neglected denizens of the area, homeless people and immigrants whom “respectable” Angelenos prefer to ignore (usually successfully).

Perhaps 5,000 or more homeless women, children and men live in Downtown. One of the book’s writers estimates many, many more. Van Hoek skillfully documents the tent cities that pervade the area, illustrating the squalor and suffering of the population. Underneath the glitz and glamor are the forgotten souls, the bleakness and intractable despair of lost lives. Hundreds, probably many more, don’t even have the luxury of tents (Figure 3). They live in makeshift cardboard boxes, scattered daily by the natural elements and human cruelty and avarice. Toilets and other sanitary facilities are woefully deficient for this population. This harsh reality is painstakingly and skillfully documented in this remarkable volume.

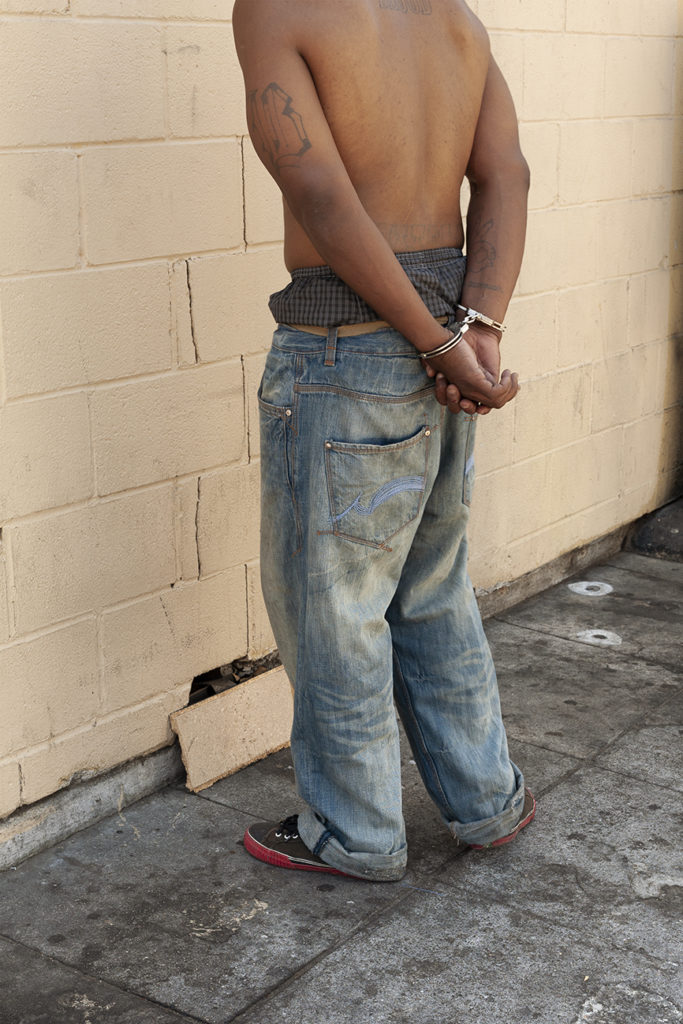

Among the most distressing images of van Hoek’s photographs are the criminalization of the poor. Young men in handcuffs are a relentlessly common sight not only in Downtown (Figure 4), but throughout every region of the city (and, indeed, throughout the entire country, where poor people, especially those of color, barely survive amid widespread affluence and material abundance).

Van Hoek’s images stand in stark contrast to the others in her book, revealing yet again the contradictions of American social, political and economic life. Another photo shows the Los Angeles police amassed on a Downtown street (Figure 5).

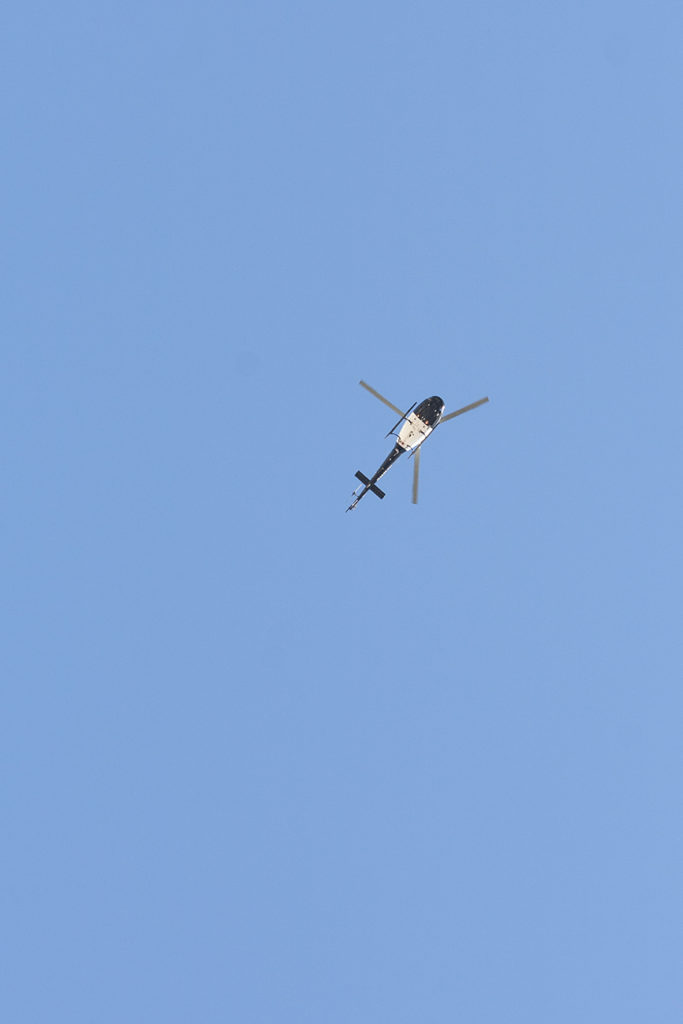

Van Hoek captures an image of a police helicopter (Figure 6), a now ubiquitous reminders of “high tech surveillance,” emblematic of the militarization of contemporary policing. It’s what the late African American photographer Willie Middlebrook called “Ghettobirds.” Even with more progressive political leadership in Los Angeles, it remains a steep climb to change deeper police attitudes and behavior, especially on race and poverty. The photographs in this book are a profound visual reminder of just why this is so.

The starkest image is the Detention Center (Figure 7), reflective of the carceral state locally and nationally. Downtown Los Angeles houses thousands of incarcerated men, women and children. Its most notorious institution is the Twin Towers Central Jail, known as a “Hell on Earth.” Brutal, understaffed and full of seriously mentally ill inmates, it’s a place that should have been closed decades ago, a moral and visual blight not only on the neighborhood and region, but also on the entire nation. Even with the recent election of a more moderate replacement for our fascistic-minded former sheriff, it’s difficult to expect much change.

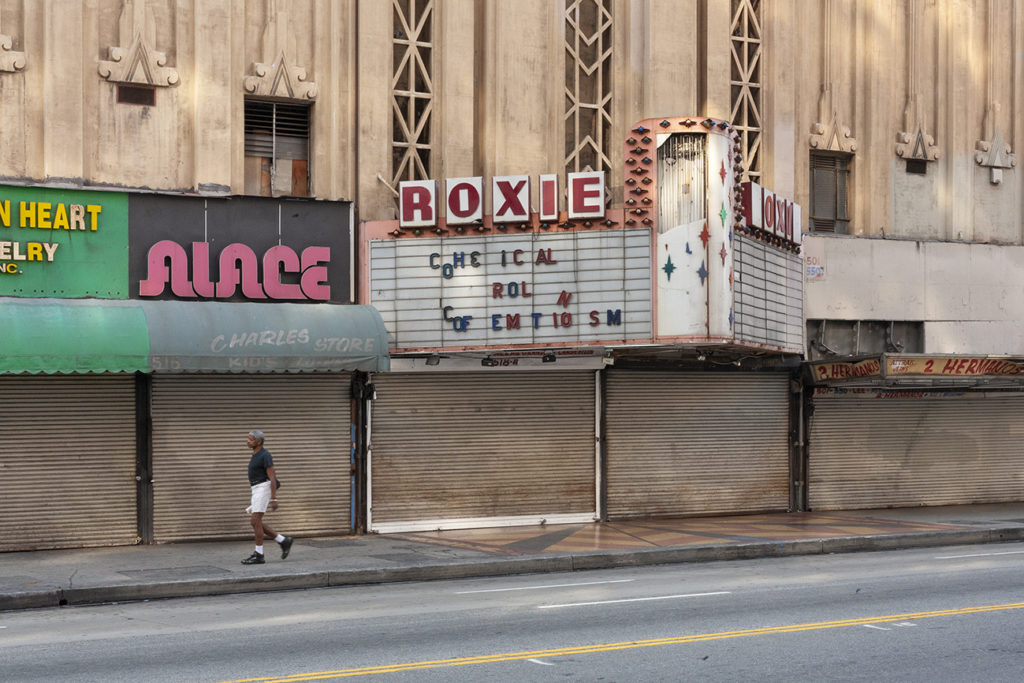

The other works in this book, like the bleakness of many Downtown streets, shuttered stores, and empty lots (Figure 8), help solidify van Hoek’s reputation and stature as a key figure in contemporary documentary photography. That longer tradition of visual social commentary in America and throughout the world has been a hallmark of artworks that encourage audiences to think more critically about vital social and political issues. Her works add to that of distinguished predecessors and contemporaries such as Americans Jacob Riis; Lewis Hine; Walker Evans; Dorothea Lange; Margaret Bourke-White; Gordon Parks and David Bacon.

I have always wished that I could like and enjoy Downtown Los Angeles. I cannot, especially after devouring “Notes on Downtown.” At best, I tolerate it because I regularly take advantage of some of its cultural attractions and some of my personal research activities occur there. But awareness is the wellspring of change. We can only hope for the best.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.