A Terrified Person in Hiding Once Lived Here

Steve McQueen’s “Occupied City” brings a human-scale map of Nazi-occupied Amsterdam vividly to life. An image from Steve McQueen's 'Occupied City." Courtesy of A24.

An image from Steve McQueen's 'Occupied City." Courtesy of A24.

At a languidly paced four hours and 30 minutes, “Occupied City” is a demanding and haunting rumination on the passage of time and the nature of cultural memory. Set in director Steve McQueen’s adopted home of Amsterdam, and written by his wife, the Dutch historian and filmmaker Bianca Stigler, the A24 documentary is also a deeply personal collaborative examination of the tumultuous history hidden beneath a city’s surface. Filmed when public COVID measures rendered the city empty, the movie consists largely of exterior scenery, the kind normally deployed as establishing shots or transitions. But here, the history of each building is the point, as detailed in voiceover narration of events that occurred at each address under Nazi occupation. The film does not so much observe the past as it does superimpose it onto the present, until its invisible specters become living presence.

It is a testament to the film, and to Stigler’s detailed research, that the Anne Frank House, one of the world’s most famous World War II museums, does not appear in “Occupied City.” This is because of Amsterdam’s sheer abundance of stories about Dutch Jews or Roma and Sinti people in hiding, and of Jewish and communist resistance to the occupation. According to McQueen, a hypothetical 36-hour version of the film could be woven from all the footage he shot, at locations with their own historical significance. The tales collected here haven’t been exactly lost to history — they are drawn largely from Stigter’s book “Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940-1945” — but the movie’s runtime serves to emphasize the volume of available records, even without referencing the city’s best-known, most-documented Holocaust victim.

McQueen’s subtle and often surprising use of audiovisual contrast proves unexpectedly poignant in a film that could have been a standard academic inquiry into Nazi horrors.

But McQueen’s narrative and aesthetic techniques are no exercise in repetition. Actress Melanie Hyams’ voiceovers deploy a neutral cadence to the (intended) point of sounding cruelly clinical as the stories of atrocity pile up. After recounting each act of resistance, and listing the names of deportees or persons in hiding, she reads off the address in question. When the street number or building no longer exists, and the accompanying image shows a vacant lot or much newer construction, Hymans ends with a single word, always skipping a beat to maximize its power: “Demolished.” The loss of these physical spaces symbolize the loss of one person or family’s life story.

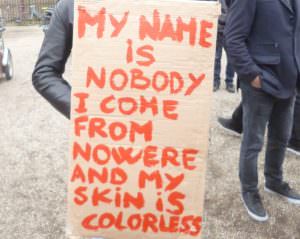

The editing and choice of shot selection often take unexpected narrative turns. Historical tales of protest against fascism are mirrored with modern demonstrations against COVID masking mandates, shot at a distance, as though the camera were privy to a wider (and in this case, more ironic) view of history than the protesters. In other scenes, McQueen and cinematographer Lennert Hillege inch closer to their modern subjects — sometimes physically, sometimes by using longer lenses — to capture rallies calling for immigrant liberation, climate justice and Palestinian freedom. These demonstrators, on the other hand, are captured with intimacy, as the tight and crowded frames (coupled with Hyams’ descriptions of previous anti-authoritarian protests at these sites) ground these movements in a distinct and tangible history. These subjects feel connected — physically, spiritually — to the ground on which they walk.

McQueen’s subtle and often surprising use of audiovisual contrast proves unexpectedly poignant in a film that could have been a standard academic inquiry into Nazi horrors. Stories of the Third Reich’s attempts to eradicate art and history are paired with shots of modern museums dedicated to preserving them. But this dedication is limited, and hours later, McQueen holds them accountable. For a city whose every street corner appears to house the memory of a vital chapter of Jewish history, Amsterdam has only one open-air memorial to the Holocaust, which stands in the former Jewish ghetto of Jodenbuurt and opened in 2021. Like its former citizens, it remains segregated.

After its premiere this summer at Cannes, I heard one critic derisively describe “Occupied City” as more befitting of a museum exhibit than a movie theater. I disagreed then, and even more so now, after a second viewing. In a museum context, viewers might wander in and out of a dedicated exhibition, catching only slivers of the whole story as they stroll past a projection on a blank wall. This ignores the purpose of the film’s runtime, and the cumulative impact of its widespread, multifaceted anecdotes, interspersed with dreamlike interludes of McQueen’s camera floating through tram cars and darkened streets. To experience its 270-minute runtime in silence — minus a gracious 15-minute intermission—is to relive the past as some lost sequence of human, and urban, DNA. It allows us to imagine the lives lived and lost in buildings that can be felled, but whose echoes can never be demolished.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.