In Amsterdam, Refugees Find Shelter From the Storm

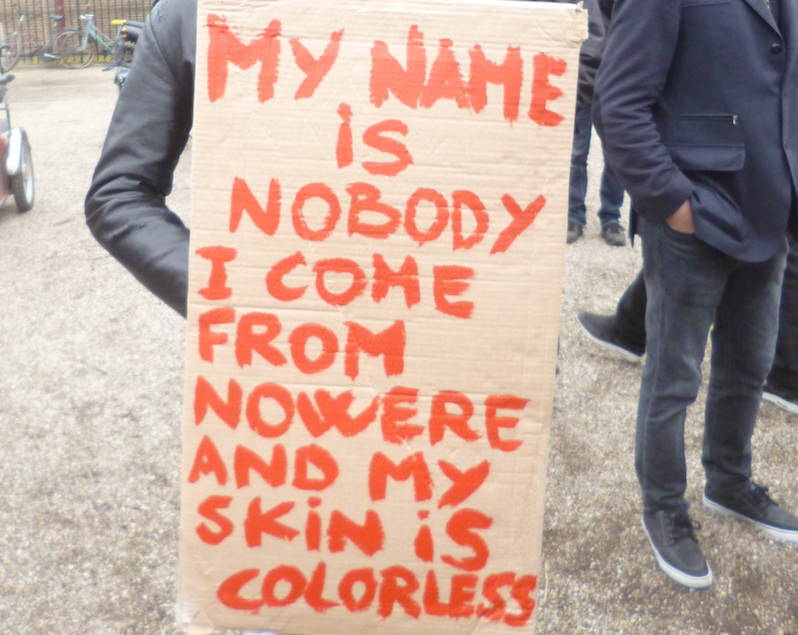

A life of displacement is hard, some Europeans oppose the influx and the bureaucracy is not all it could be. But small acts of kindness and human connection ease an anxious situation. Here's one volunteer's account from a refugee center. An activist at a recent pro-refugee demonstration in Amsterdam. (bart plantenga)

An activist at a recent pro-refugee demonstration in Amsterdam. (bart plantenga)

Recognize yourself in he and she who are not like you and me. —Carlos Fuentes

AMSTERDAM—Hassan, the Syrian with the contemporary wave-of-bangs-sweeping-across-the-forehead haircut, maybe 19 years old, went out for exercise at the local pool, where people can swim for free on Sundays. He cut a fine figure, with his tight jeans, his T-shirt fitting just right, a calm smile neither reserved nor ostentatious, and an air of innocence not yet crushed—despite everything.

|

Some names have been changed in this article to protect personal safety. |

His mates met him at the revolving door in the lobby of the refugee center. They were gesticulating, arms flailing in disbelief and indignation, and yelling in Arabic. Then someone held up a smartphone so Hassan could see for himself. A video showed his brother being beheaded by Islamic State troops. All color drained from Hassan’s face as he sank into profound grief.

For three days, Hassan accepted condolences from everyone connected with the refugee center: the other refugees, volunteers, management, security guards. Afterward, he withdrew deep inside a very private self.

You can imagine why I get angry when Europeans—a minority of them, but a very vocal and irritating one—claim that the majority of refugees flooding Europe are fortune-seeking, economic refugees faking their misery.

This obstinate, fact-free stance was evident in February during an anti-refugee rally in Amsterdam by the German-rooted, anti-Islam movement Pegida. Organizers tried to pass themselves off as righteous victims after counterprotesters rejected their message of hate as immoral. They scurried toward the news cameras to pose with their German flags as innocent practitioners of their democratic right to, well, hate.

This followed rancorous public protests against the establishment of temporary refugee centers in various small Dutch towns—the NIMBY phenomenon. Meanwhile, Geert Wilders, far-right leader of the Dutch Freedom Party, proposed that Muslim male refugees be incarcerated in asylum centers as a precaution in the wake of the New Year’s Eve sexual assaults in Cologne, Germany.

That same afternoon, pro-refugee forces held a rousing counterdemonstration a few blocks away that included fiery speeches and inspired chanting and drumming at the “Dockworker” statue, erected in honor of the first uprising against the Nazis by Amsterdammers, in 1941. The site is right across the street from the Jewish Historical Museum.

The pro-refugee demonstrators showed that they’re not just some polite, apathetic majority. Many, however, prefer a low-key, pragmatic approach to the crisis, and we all know that philanthropy and good deeds are not sexy news.

Twice weekly, I bike to work at a large refugee center in Amsterdam’s Zuidoost, the southeastern district, which has a large immigrant population. It is one of the city’s four areas of not-so-temporary refugee residency.

In September, when I began working here, the center housed 600 refugees from Syria, Eritrea, Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran, plus a few from Albania and Mongolia. Since Christmas, families have moved to better facilities; now a more comfortable population of 200—mostly Syrian men and a sizable group of Eritrean women and men—remains at the center.

Enter the refugee center lobby and you enter a whirlwind of activity: food being sorted, public transportation tickets and aspirin being handed out, medical staff offering prognoses, interpreters resolving misunderstandings, donors dragging in big bags full of used shoes, refugees slouched in chairs and fixated on their smartphones.

The work I do is interesting, but not heroic. For heroics you turn to two indefatigable volunteer coordinators: Billy Jean and Erik.

Billy Jean, named after pioneering tennis star Billie Jean King, is always willing to lend an ear and a smile and is seemingly on call 24/7. She’s Dutch-Surinamese. An agnostic, she grew up curious about the faiths of others. She works two jobs, as a social worker and as a barmaid. Add her 35 hours at the center and she’s clocking over 70 hours a week. “I sleep maybe four hours a night,” she says.

Erik is 50-ish. He worked with disabled kids until he decided to travel at his own expense to Greece to work on the front lines, helping refugees arriving by boat. When he returned, a friend tipped him about a position at our refugee center, only blocks from his home, and he leapt at the opportunity. He was so enthusiastic that he refused a paid position in order to be freer to coordinate volunteers and help refugees in a more flexible, intuitive, hug-and-joke manner that this kind of work requires as antidote to insensitive bureaucracies. He is the refugees’ best advocate, therapist, counselor and consoler.

Tragic tales lurk inside the heads and hearts of each refugee. One older woman is recovering from a telephone conversation with her husband, who is back in Syria. She’s lived here for months with a secret: Her teenage daughter died of dehydration en route to Amsterdam, and she buried her in the Libyan desert. She didn’t tell anyone at the center and she didn’t dare tell her husband because she knew he’d be emotionally shattered. When she finally did, there was an immense outpouring of grief on both ends of the telephone line.

In working with refugees, you need good people and stories to buffer the tendency to be disillusioned by mankind. One day our tailor, Moustafa, who’d been begging for a sewing machine so he could do something, received two. So there are now two tailors, and they can alter jeans in about 10 minutes and do hundreds of alterations per week. One day, Moustafa was slumped over his machine. He needed a new belt and oil for it or he’d risk going from playing a role of importance at the center to being a nobody. Erik placed a request for the items on the Facebook page Wat is nodig (What is needed), dedicated to coordinating refugee needs and donation offers. A day later, a belt arrived, someone delivered a small bag filled with tubes of oil, and Moustafa, with a proud grin, went back to altering garments for a long line of refugees.

Jiad, an artist, was terribly depressed when he asked Erik if he could make a mosaic for the lobby. Everyone reacted enthusiastically, including the “shrink,” who said there was no better way than art to pull an artist out of a depression. Someone made good on Erik’s post requesting art supplies, delivering an entire shopping cart full of tiles. Jiad became a new man overnight. His mural, along with one made by Firas and Nadeem, is now the spot where everyone at the center goes to pose for selfies and group shots.But there are plenty of sad stories at the center as well. Erik mentions a young guy who broke up with his girlfriend here. She pleaded with him not to end the relationship; the more he insisted he wanted to end it, the more desperate she became. Finally, she threatened him physically and gave him an ultimatum: Come back to her or she was going to commit suicide. She later slit her wrists—“there was lots of blood,” Billy Jean recalled—but she survived and eventually transferred to another facility.

I work mostly in the Welcome Store, initially established by the Red Cross and eventually taken over by Venzo, a volunteer organization. It’s run by some intrepid refugees who help with the computers and unload trolleys containing mountains of clean, folded, donated clothes and shoes—so much had been donated by December that it was almost too much.

The refugees can “shop” here for free clothes, bedding, towels, hats and scarves donated by Dutch students, church groups, charities, banks and companies such as Nike and Rituals. The public waterworks donated 600 water bottles; a charity organization raised money to buy underwear for all 600 refugees.

I like to work hard to help those who have so little left of their pasts. When I saved a particular sweater for one woman and held it up for her, she rewarded me with a broad smile.

As I work with these people, I keep my parents in mind. They were economic refugees who emigrated from Amsterdam to central New Jersey in 1960. As a result of a sluggish post-World War II economic recovery, the Dutch government encouraged emigration with financial incentives. My father probably thought the future for a metallurgical engineer was in America. That he was wrong is beside the point. Perhaps he was motivated also by mounting Cold War tensions, having been plucked from the streets of Amsterdam as a 17-year-old by the Nazis to be a forced laborer in a Berlin factory, and then witnessing the brutal liberation of Berlin by Russian troops in 1945.

It’s good that people like Erik want to discard that most clichéd aspect of giving: the false, destructive dichotomy between giver and receiver, the pathetic and the heroic. He believes in empowering refugees so they can regain pride and overcome their personal tragedies.

Basem works in the dispensary, where people go for a squeeze of shampoo, a bar of soap, sample bottles of lotions and creams.

I related to Basem early on. An English lit student who left Syria in his third year at Damascus University, he’s a pacifist who refused compulsory conscription. He has a healthy live-and-let-live attitude, and his English is excellent. That he sleeps until midday, after having been up late into the night, sets off a running joke when he saunters into the store, sleepy-eyed but grinning.

Boredom is the major adversary here, so I found a university course for Basem. We had immediate, enthusiastic reactions from both Amsterdam universities I contacted, with two sympathetic professors helping to enroll him in a literature and politics class at the Vrjije Universiteit (Free University), a 10-minute metro ride from the center. The class helped him purchase the required reading, and all was copacetic—until I received his apologetic message: Despite his best intentions, he found he couldn’t concentrate on his studies because of the news—or lack thereof—coming out of Syria.

He explained that his father was cooped up at home for weeks at a time and hadn’t seen his other son, who lives only a few blocks away. The war and bombardments are one thing, but the biggest fear of men in Damascus is to be forcibly recruited by soldiers from one contingent or another; to refuse means being shot.

As a result, Basem is increasingly anxious, easily distracted and unfocused, conditions exacerbated by a lack of deep sleep, constant uncertainties, the lack of privacy, the sudden displacement of friends who may get only 24 hours’ notice before they are transferred to the next camp and the next phase in their process.

Basem remains circumspect and reasonably upbeat, but after five months he has grown weary of the interminable legalization process and the uncertainties surrounding his status. Such helplessness leads to erratic behavior, roller-coastering emotions, sudden outbursts of frustration and grief.

Don’t get me wrong. Basem and the other refugees appreciate the outpouring of support from so many Dutch people: the clothing, soap, shampoo, bicycles, skates, the courses, outdoor activities, outings to concerts and museums. But the ad hoc benevolence of individual Dutch people is not enough to compensate for what is perceived by volunteers and refugees alike as the official sluggishness of the immigration services bureaucracy. Most frustrating is the inscrutability of a system that offers no insight into the rules by which it operates.

Basem and I were talking when our conversation was interrupted by the departure of three Eritrean women. It was a tearful send-off as yet another close-knit group disappeared into the bureaucratic abyss. Then some folk musicians arrived with arms full of unusual acoustic string and percussion instruments. Just then, a so-called “famous” Syrian singer stopped by for a chat. Some consider him arrogant. He has bragged about his fame in Syria, his gig at a Middle Eastern club in Rotterdam, and how he is destined to win an upcoming talent show. He snickered when the ragtag bunch came in with the instruments, mocking them as amateurs of no consequence. Billy Jean and Erik were discussing the Flierbos Got Talent Show with the organizers at the Q-Factory, where the gala event will take place. There will be singers and musicians, a Syrian national break dance champ, acrobats, spoken word—all to be judged by a panel of well-known Dutch entertainers.

Fadi, a pilot back in Syria, dropped by for a quick hello and a quip in Arabic before moving on. He’s a generally jolly character with a lot of color in his cheeks, but he has his ups and downs. He left his entire family behind, and his wife is about to have a baby he may not see for years.

Several weeks ago, Fadi had the day of his life. For his birthday, Erik placed a request for anyone connected with Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport to arrange a tour and plane ride for him. Two airline reps responded. Martinair offered to let him fly a plane—with a pilot next to him. After takeoff, he was given a midair birthday greeting by two passing planes, whose pilots dipped their wings as they passed. He spent the next day at KLM headquarters, where he passed through high security, enjoyed a tour and a lunch and operated a flight simulator. He was on cloud nine for days.

But that seems like ages ago. Just the other night Fadi had to be taken to a hospital because he was manic, complaining of heart palpitations and panic attacks. Basem escorted him to help with translation and keep him company. They spent seven hours there. Fadi had to be sedated; the doctors said he was suffering from stress—perhaps the anxiety of waiting, seeing others who’d arrived at the center after him moving ahead of him in the process, or simply not knowing what his fate will be.

Erik’s request for makeup and a curling iron for Amira, a lively Syrian hairdresser, came through the same day, and she was over the moon. She has been undergoing dramatic mood swings, but now she’s upbeat. She found a sexy white turtleneck in the shop to wear to a party she had been invited to. I saw her later, and she was a knockout. I gave her a double thumbs up, and she smiled warmly. See how easy it is to make someone happy?

Loes, my co-worker, and I helped a “super famous” Syrian actor find something in the store that resembled a mailman outfit for his comical/dramatic solo in the talent show semifinals. He was as inspired as if he were preparing for a Shakespearean debut.

I heard that Bassel, a barrel-chested, dark-metal Syrian guitarist, is going to do a metal version of Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” in the semifinals. I hope he rocks the house, blows away the judges and beats that arrogant singer. I hope the actor, too, does well.

Actually, I hope everybody wins.

Editor’s note: Also see bart plantenga’s “Report from inside a Refugee Center in Amsterdam” in Vox Populi.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.