The Art of Documenting the Undocumented

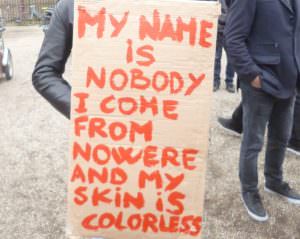

Dutch conceptual artist Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries takes the plight of refugees as his latest project. Images from Dutch artist Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries' refugee project outside Amsterdam's NDSM cultural hotspot. (Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries)

Images from Dutch artist Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries' refugee project outside Amsterdam's NDSM cultural hotspot. (Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries)

It’s December 2007, and the young Dutch artist Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries has called together some adventurous, non-acrophobic squatter volunteers. He wants them to help him climb a gigantic billboard along the A28 highway outside the city of Zwolle and unfurl an 1,100-square-foot banner across the billboard. In 5-foot-high letters, the banner declares simply: “I FEEL FOR YOUR MISERY” (“IK BEN BEGAAN VAN JULLIE ELLENDE”).

“The question is: What can an artist do to alleviate some of the misery in this world?” Himmelsbach says as we sit in his ramshackle studio. He has set up shop inside a converted storage space with a self-built toilet in the industrial wasteland of super-hip Amsterdam North, cynically awaiting the inevitable wrecking ball of gentrification. “You see a stream of misery via TV and the internet and so [I ask]: ‘What kind of statement can I make?’ “

Himmelsbach’s art offers an answer: Express simple sympathy for others. By presenting a series of probing questions, mystifying strategies, and engaging dialogues, he aims to communicate with people not usually reached by contemporary art. His kind of conceptual art doesn’t hang on walls and carries no price tag. Later, he learns that a fundamentalist preacher in the heart of Holland had incorporated his humanitarian billboard message into a Sunday sermon.

Himmelsbach feels that speaking to people leads to speaking with people. It’s something like walking a cute terrier in any park anywhere—in no time the dog becomes the talking point, opening up two strangers to interact with one another. Art is Himmelsbach’s dog.

More conceptual outreach: During two months in 2010, 25 Amsterdammers responded to Himmelsbach’s posters advertising “ONE DAY FREE HELP.” They took him up on his free handyman offer. He went to people’s homes to fix electrical outlets, leaky faucets—for one Dutch-Indonesian artist he moved a heavy refrigerator, cleaned behind it and got rid of the mice plaguing her home.

“For me its about collaboration and arriving at something together,” he says. He insists clients help him help them because “by working together, you end up in new situations and conversations, while you’re fixing something, and that’s something I really like. It’s about what’s out there in life.”

His work is reminiscent of Amsterdam’s 1960s ludiek (playful) happenings by artists associated with the Provos, politically minded anarcho-pranksters inspired by Dada, John Cage, Joseph Beuys, the Situationists (but funnier) and the Fluxus movement (but more political).

The Provos are most famous for their White Bicycle Plan to place free bicycles throughout Amsterdam to alleviate congestion and pollution. Their works fused art and life: Their Throwaway Automobile folded up into an ordinary suitcase; they proposed anti-authoritarian crèches; and they set up the Kabouter (Gnome) Party. Through that party, they not only distributed counterfeit money but also got elected to Amsterdam’s City Council, where they proposed flower gardens for the roofs of the city’s trams and promoted organic food.

Himmelsbach is inspired by their legacy of turning political discourse on its pointy head via absurd contrarian events, playing not only “for their own pleasure” but also for “activating the larger project of unleashing the hidden creativity in their audiences,” as Marjolijn van Riemsdijk writes in her book “Assault on the Impossible: Dutch Collective Imagination in the Sixties and Seventies.” This humorous approach speaks to Himmelsbach because, as he puts it, “although I’m political and have an activist background, I am allergic to finger-wagging moralism.”

Outsiders became his role models in his teenage years, especially when it came to music—he gravitated toward punk, industrial music and Marilyn Manson, and he eventually befriended the local, extremely absurd punk-Fluxus band, the F*ck*ng B*st*rds, which created a special kind of delirious chaos.

By age 16, he’d had enough of Friesland. He thought he’d become a squatter and do outdoor art murals on city walls, but that didn’t pan out. He eventually moved to Zwolle, an hour east of Amsterdam. It’s a pretty, medieval town, home to mustard and monks, older than Amsterdam, now more of a bedroom community and ultimately a place he stayed “seven years too long.” As he puts it, “You wouldn’t want to be found dead there.”

But creating art allows a teenager to own his boredom and recycle it as time well spent. “And here you build a certain kind of world of fantasy and experience,” Himmelsbach says. “And this helps determine what you end up doing with yourself.”

He didn’t get into art school, so he began programming strange underground events and noise concerts, and he helped establish a squatter cultural center where he fell in with a “family of art pranksters. I just loved anything that seemed unacceptable.” Despite this attitude, he eventually did manage to graduate from Zwolle’s reputable ArtEZ Art Academy in 2009.

With a significant CV of anti-establishment art activities and an appreciation for creatively transforming alienation into something engagé, upon hearing the tragic stories of rejected asylum seekers, he rediscovered his empathy for outcasts and began figuring out how to reach them. The Netherlands is a multicultural hub and has been a destination for refugees—Descartes, Portuguese Jews, Mennonites and gays—since the 1600s. The sudden influx in 2015 of Syrian and Eritrean refugees, who are pretty much guaranteed residency permits in the Netherlands because they come from officially recognized conflict zones, overshadowed the plight of rejected asylum seekers from places like China, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, the former Yugoslavia and Kosovo.

These rejected asylum seekers arrived with no official documents, making them the equivalent of stateless nobodies in the eyes of officials. “They didn’t receive emergency or temporary residency status, so they ended up in a kind of no man’s land,” Himmelsbach says. Many end up in the underground economy or on the streets.

He learned more about these asylum seekers at We Are Here, a community center and tent camp in Amsterdam West that aids refugees caught in the grip of a system ill-equipped to handle their kind, often leaving them homeless, jobless and without status. Their plight inspired Himmelsbach’s most provocative-evocative art project to date, “Paper Monument for the Paperless.”

“I accept it as my little hit,” he says with bemused reticence. “It’s a vehicle for me to break through my own spectatorship to come into contact with these people. Why not work together with them to give the faceless a face—document the undocumented?” He began by trying to donate his illuminated “REFUGEES ARE OK” (“VLUCHTELINGEN ZIJN”) sign, offering to put it up on the roof of the We Are Here building.

“But it was too ambiguous,” Himmelsbach says of his initial efforts to work with the refugees. The organizers at We Are Here did take him up on his offer to do workshops, and he settled on woodcuts. “But the workshops did not go well because the undocumented couldn’t concentrate, were worried about other things,” he says. “And so I went with a photographer and took photos of most of the faces and invited some artists to help with the woodcuts.” But, then he asked, what should be done with all these beautiful “faces that fall between the cracks of society?”

Himmelsbach decided to post the images of the refugees around Zwolle. “I thought these faces needed to be seen around the city because it’s really surrealistic: Who are these faces, and who’s spending so much time on these anonymous humans?”

Luckily, in this case, the tale took a bureaucratic turn. “I wanted to give something back to these people to aid their visibility,” Himmelsbach says. He applied to and was accepted in the European Union’s Europe by People program, which he says involved “endless meetings and marketing strategies. It was unclear what we were supposed to do in building a bridge between cities and administrators. This brought me back to my idea of reproducing the woodcuts.” Eventually, the program sponsored the printing of the woodcuts in a newspaper format with one portrait per page.

“The idea was to link the newspaper back to the people,” Himmelsbach says. Amsterdam organizations like Migrants to Migrants (M2M assists the self-organization of refugees on the street) and The Beach (a sustainable innovation and community design project) helped him reconnect with some of the original models, so he could give them woodcut prints of their faces. He and The Beach organized a reunion “where we looked back but also toward the future. We walked through neighborhoods with 10 of the original models, carrying the woodcuts on signs, and ended up in a Turkish mosque to talk over tea.”

People who pick up the free newspaper are encouraged to poster walls with the enclosed woodcut prints. People do—and so does Himmelsbach. Every week he sets out for a new destination—Enschede, Amsterdam Central Station, Amsterdam South, Brussels—often wheat-pasting them to the wooden fencing at construction sites. And so, if you take a bike ride through Amsterdam, you will eventually see some of these mysterious faces staring back at you.

Wilders rails hard against the art world, its elitism and the wasting of taxpayer money on subsidizing art few can appreciate. He disparagingly refers to art as a “leftist hobby”—”hobby” in the sense of “worthless,” as in people going hungry while snobs tinker around with incomprehensible art. He advocates dramatic cuts in arts funding.

So Himmelsbach created the Wilders Webstore to détourne Wilders’ “leftist hobby” notion by making Wilders himself the consumed object. The webstore (and sometimes street stands) sell consumer art products such as Wilders-themed welcome mats, hair spray, Band-Aids, duvet covers and adorable Wilders garden gnomes, so that Wilders becomes the object of his own contempt. As Himmelsbach muses: “It’s becoming increasingly difficult to live off our art. The funding faucet is closed, and so we’ve decided to join the greed economy and get rich off Geert Wilders.”

Himmelsbach’s current favorite work is his “Monument for Okay People,” which was erected near the Netherlands’ geographic center, on a dike along the Veluwemeer in Biddinghuizen. It recognizes the 99 percent who are never mentioned on any monument anywhere. “These people are not bad, not good— they’re just OK,” he comments.

Dutch author Simon Carmiggelt wrote in 1968 of prankster-artist Theo Kley: “Because he does not get lost in the wordy, tedious fuss that realization of these projects would necessitate … but daringly pushes open the window with a view on a better world, I find these conceptions very inspiring. In any case … he has started the assault on the impossible.” These words could easily describe Domenique Himmelsbach de Vries as well.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.