Dunkirk Represents a Big Disgrace and a Great Moment in British History

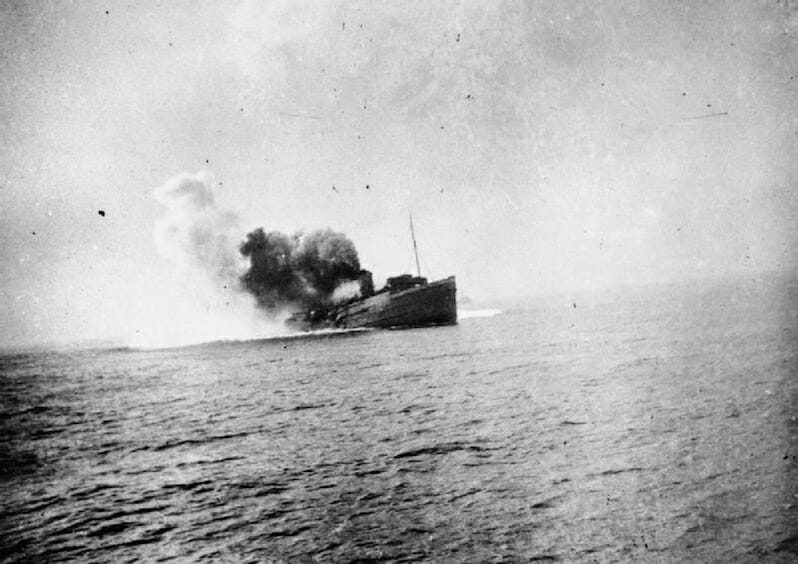

Winston Churchill called it both a colossal military disaster and a miracle of deliverance. The Isle of Man steam ferry SS Mona's Queen sinking after striking a mine off Dunkirk on May 29, 1940. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Isle of Man steam ferry SS Mona's Queen sinking after striking a mine off Dunkirk on May 29, 1940. (Wikimedia Commons)

By Allen Barra

The Isle of Man steam ferry SS Mona’s Queen sinking after striking a mine off Dunkirk on May 29, 1940. (Wikimedia Commons)

To read Allen Barra’s review of the film “Dunkirk,” click here.

More than any other story to come out of World War II, with the possible exception of the Battle of Stalingrad, and perhaps more than any story to come out of all 20th century wars, Dunkirk looms larger—more Homeric, more heroic—the closer one looks.

That’s Dunkirk the evacuation, not Dunkirk the battle.

The battle, which began on May 26, 1940, was correctly called by Winston Churchill “a colossal military disaster.” The evacuation was correctly called, also by Churchill, “a miracle of deliverance.”

Here’s the background: On May 10, 1940, the so-called “phony war” in which neither side fired a shot finally ended as the German Wehrmacht invaded France. Most British and American military experts regarded the French army as the strongest in the world. The assumption was that with France’s and Belgium’s armies and the addition of the 300,000-plus British Expeditionary Forces (BEF), the strength of the Western nations was at least equal to that of the Germans.

The assumption, too, was that the French were in a strong defensive position with the heavily fortified Maginot Line on the French-German border. The 100-mile front of the Ardennes Forest in southeast Belgium was thought to be impenetrable, at least by tanks, and was therefore lightly defended by the French.

Wehrmacht commander Erich von Manstein, however, had determined that the Ardennes was indeed penetrable. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s entire Army Group A came through the forest with nearly 1,800 tanks, supported through the air by more than 300 Stuka dive bombers while Gen. Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B engaged British and Belgium forces to the north which, though they were lightly armored, were outfitted with British artillery.

Von Rundstedt’s divisions came through the forest, crossed the river Meuse, and, practically before the Allies could respond, were in French territory. This was “blitzkrieg”—lightning war. Generals who were still thinking in terms of trench warfare as in World War I were entirely unprepared. Most Allied anti-tank guns were ineffective against German tanks. Some units had no anti-tank weapons at all. One luckless division faced the armored divisions of a soon-to-be famous commander, Generalmajor Erwin Rommel, without any anti-tank guns.

Eighteen days after the German invasion, King Leopold III of Belgium shocked the British and French by unconditionally surrendering his country. The British were about to move divisions into the gap created by Belgium’s surrender when they realized German armor was practically behind them. Panic began to set in among both British and French soldiers who were seeing their first combat. As one British officer later put it, “We were sent into something that we couldn’t cope with.”

Several myths would grow out of the German invasion of Belgium and France. One was the nature of the blitzkrieg itself. For the next couple of decades, military historians would write about how fast-moving columns of German armored vehicles crashed through Allied lines, quickly destroying all resistance. The Germans did move quickly, but as was later proved, tanks and armored cars need enormous quantities of fuel to sustain momentum and therefore can’t move much faster than the supporting infantry.

The real weapons of the blitzkrieg were waves of Stuka dive bombers, which the Allies were unprepared for. The coordination of the German ground-air attacks left the French and British staggering. Fear and confusion began to take hold of the Allied troops. Inevitably, a rushed and uncoordinated retreat ensued. The French slowed some German units by flooding marshes, and somehow, amidst what was perilously close to chaos, the Allies set up a corridor, which led to the most likely evacuation spot, the port of Dunkerque. Most of the burden of defending the corridor fell to the French.

Another myth of Dunkirk is that the French army was demoralized and collapsed under the German onslaught. In fact, the French, though they were as befuddled by the new German tactics as the British, fought courageously. Casualties were enormous with the BEF and their allies losing 68,000. The most heroic fighting of the entire battle was by the French First Army, whose 40,000 men fought a delaying action against seven German divisions, three of them dreaded Panzer units.

Nearly the entire French First was killed or captured. One French officer wrote Premier Paul Reynaud to explain why he was committing suicide: “I’m killing myself, Mr. President, to let you know that all my men were brave, but one cannot send men to fight tanks with rifles.”

Nine days after the Germans crossed the border, Gen. Thomas Riddell-Webster, at a meeting in the British War Office, spoke for the first time about the possibility of evacuating the men of the BEF. There was no feeling of urgency, but Vice Adm. Bertram Ramsay was given the assignment of preparing for the rescue.

By the next day, however, events had changed drastically. With German tanks rumbling toward the coast, the British brass discovered a horrifying fact: The entire BEF was in danger of being trapped. The situation worsened every day with frightening speed. Though no word was given to the British press or even their French allies, Operation Dynamo (named for the Dynamo Room which provided electricity for naval headquarters at Dover Castle) was put into effect.

A bizarre-looking fleet of barges, ferries, fighting boats and pleasure craft was assembled. The navy quickly alerted commanders of craft on the Thames with drafts shallow enough to skim that part of the English Channel. Lifeboats were stripped from ocean liners. Terrifying as the 26-mile run was, scarcely anyone turned back. One British captain who took a hit from a German torpedo boat comforted himself by thinking, “Gary Cooper always finds a way out.” (He was apparently recalling Cooper’s 1937 film, “Souls at Sea.”)

Throughout history in times of war, the British have always counted on their navy to save them. But the sea around Dunkirk was too shallow for most large naval vessels, and many Royal Navy destroyers were occupied in waters around Norway. (This ultimately proved to be at least a partial blessing as most German submarines would not risk the shallow waters.)

One of the first British destroyers to approach Dunkirk sent back an ominous message: “Plenty troops, few boats.” The order went out to the stunned British troops, “Get as near Dunkirk as you can, destroy vehicles, and every man for himself and good luck.”

The British prayed for deliverance, and their prayers were answered from an unlikely source. Hitler halted the German tanks about 20 miles from Dunkirk. Why has always been and always will be debated. One definite factor was commander of the Luftwaffe Hermann Göring, who argued vociferously that his planes could destroy the British without the aid of ground forces. (Less than two years later, Göring would convince Hitler to make the disastrous decision to leave the German Sixth Army encircled at Stalingrad, believing that his air force alone was capable of supplying them.) Göring can easily be blamed for the two most idiotic decisions made by the German high command in the war.

Göring, though, had not counted on two things. The first was intense fog which gave Britain’s rag-tag fleet of nearly 900 vessels effective cover as they picked up British and French soldiers. The second was Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF). The British had just perfected a formidable new fighter plane, the Spitfire, which could outturn and out dive the German Messerschmitt Bf 109. At the first engagement, the outnumbered planes of the RAF downed 38 German plans at a loss of 14 of their own. All in all, Fighter Command flew 3,500 missions against the Luftwaffe. They didn’t defeat the German air force so much as hold it at bay.

A third factor blunted the effectiveness of the German planes: The shore of the Dunkirk harbor was so soft that many bombs failed to detonate. Dozens of bombs remained stuck in the sand for more than five years before they were exploded by detonators from the Allied armies after the war.

One British private later recalled that seeing the White Cliffs of Dover, he felt as if he had gone “from hell to heaven. We felt like a miracle had happened.” By June 4 the miracle was complete. That afternoon Winston Churchill spoke before the House of Commons, which was filled to overflowed. He was greeted with a rousing cheer, but his speech wasn’t calculated to inspire good cheer. Instead, he delivered perhaps the most famous speech of the 20th century, one that began, “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” But, he warned, “We must be very careful not to assign this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.”

Edward R. Murrow, reporting back to America, called it, “A report remarkable for its honesty, inspiration and gravity.” The next day The New York Times proclaimed: “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence.”

In the end, how important was the evacuation of Dunkirk? Start with this: If the BEF—not to mention the many thousands of French soldiers who escaped with them—had been destroyed and captured, it’s likely that Britain would have capitulated. As it was, the British army lost nearly 2,500 pieces of artillery and more than 63,800 tanks, trucks, and other vehicles—practically all of the army’s equipment. But though it would exact an enormous cost, Churchill felt that one way or another, America—and to a lesser degree, Canada—could replace the lost war material.

What would have been irreplaceable were the 224,700 British soldiers who were the only trained troops Great Britain had at the time. The Allies lost a staggering total of nearly 70,000 killed and captured in the battle and evacuation. If they had lost the other 340,000, it would have been the most colossal defeat of World War II. (By comparison, the Germans and their allies lost perhaps 300,000 in the defeat at Stalingrad, and American and British armies took about 250,000 German and Italian prisoners at the end of the North African campaign.)

The capture of the BEF would likely have taken the British out of the war and, with them, their navy and their connections to their Empire and Commonwealth countries. The Mediterranean would have become an Axis lake. Rommel would have had no opposition sweeping across North Africa, closing the Suez Canal and moving on to the oil-rich Middle East.

The U.S. would have had no base for mounting an offensive against Hitler’s Europe, and, most important, the Germans would have been free to marshal all their forces against Russia. If the Soviet Union had fallen, as it came so very close to doing, Nazi Germany would have reigned supreme over the West and practically all the world for who knows how long?

Democracy in Europe would have died an ugly death, and consider the cultural consequences. We’re talking about a vastly different world. The Britain we know now would never have been. No George Orwell (or at least no “Animal Farm” and “1984”), no Philip Larkin, no Bond, no Beatles, no BBC, maybe no Harry Potter or “Game of Thrones.” And no films by Christopher Nolan.

And who knows what the outcome of the war would have been if the U.S. had been left to face, without allies, Japan and a victorious Nazi Germany?

I’ll give the last word on the importance of Dunkirk to an American, the historian Walter Lord, author of the most enduring book on the battle, “The Miracle of Dunkirk”: “Modern war is so impersonal, it’s a rare moment when the ordinary citizen feels that he’s making a direct contribution. At Dunkirk ordinary Englishmen really did go over in little boats and rescue soldiers. Ordinary housewives really did succor the exhausted troops reeling back. History is full of occasions when armies have rushed to the aid of an embattled people; here was a case where the people rushed to the aid of an embattled army.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.