Ken Burns’ Other Lens

America’s most famous visual storyteller shifts gears in a new book. Liberty enlightening the world. New York Harbor, 1886. Photo credit: Library of Congress

Liberty enlightening the world. New York Harbor, 1886. Photo credit: Library of Congress

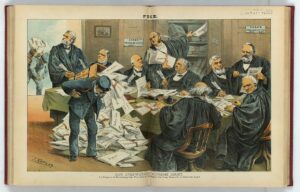

Ken Burns, the country’s most prominent television documentarian, turns from the screen to the page with “Our America, A Photographic History” (Alfred A. Knopf). The book continues Burns’ long and signature obsession with the American story, covering 180 years of history with roughly 250 black-and- white photographs taken between 1839 to 2019.

The lavishly illustrated volume ranges chronologically across famed figures, ordinary people, landscapes and cityscapes, momentous events and day-to-day life. The curated images — drawn from the National Archives and Records Administration, the Library of Congress, Getty Images and museum, university and private collections — are Burns’ attempt to delve into what he calls the “accumulated history” of the land he’s been chronicling onscreen for more than 40 years. In contrast to the propulsive pacing of his Emmy and Oscar-winning films, “Our America” allows the reader to linger and ponder over the images and their own American backstories. By highlighting the men and women behind the photographs, the book also serves as an annual of American shutterbugs and the medium of photography.

Truthdig recently spoke with Burns by phone about “Our America,” his favorite photographers, contemporary controversies around race and more.

“Our America” is your first book not tied to one of your documentaries. Why?

It was a way to go back to my roots. My father was an amateur still photographer, I was trained by still photographers, particularly Jerome Liebling, and the still photographs within my films are the DNA of what we do, the building blocks that let us communicate.

In my world and in the documentary world, I control how long you look at that photograph. I zoom in, I isolate, I direct it, but I like the purity of the old Aperture monographs and other photography books that have only one photograph per page, minimal captions and allows you to spend as much time as you wanted with the photograph. I love that. And I wanted to do something about it that would be the history of the United States, both uppercase (U.S.) and lowercase (us).

The way to do this was to start with the first selfie, a self-portrait [of Louis Daguerre] from 1839, the year photography was invented, and to proceed more or less to the present. We designed it in a way so the photographs might talk to each other visually, intuitively, obviously, structurally, politically, whatever it might be and we just allowed them to have, if you will, conversations between themselves.

The book not only pays attention to the subjects of the photos, but to photographers and the medium of photography. Tell us about some of your favorite photographers in “Our America.”

I would start with Lewis Hine and, of course, my mentor, Jerome Liebling. With the case of Lewis Hine, he’s looking at all of us. You can extend that then into the Depression era, with Ben Shahn, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans and others represented in the book are out looking at America for the Farm Security Administration, led by Roy Stryker. He was just saying, “Go out and capture us,” in the same way that I say “our.” That is to say, warts and all. Whatever you can find.

The book discusses different schools of photography, from the “Pictorialism” of Karl Struss, to the “Straight Photography” advocated by Paul Strand. What do you prefer?

The latter. Paul Strand is one of my favorite photographers. There are many other things that are done — you have the modernist and manipulation shots of [Robert] Heinecken and Minor White and others. Things going on right now, abstractions by Carl Chiarenza and others. I’m not saying they’re not good. I wanted my book to be more straight, representational, photorealist, more social documentary in its gaze.

Although you can see a variety of things, in the landscapes and intimate pictures of a pussywillow branch or girls dancing for joy or an interior of the New York City subway. Some of them are just saying, “This was,” in essence, this is. Sometimes we overcomplicate the reception of a photograph by superimposing on it the label of the particular school it may or may not subscribe to. Jackson Pollock did representational paintings and then he did the epitome of Abstract Expressionism and non-representational painting. What I want to do is be open enough in my view that I can include all sorts of things. There are all kinds of people, all of them American.

Whether you’re making a film about baseball, war or the Central Park Five, and now in “Our America,” race is a recurring theme in your work. Why do you think that race is so central to American history?

Because any serious dive runs into race. Just think of the moment of our birth — we know exactly where we were born, Philadelphia, we know exactly why — the second sentence of the Declaration, “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.” I can stop right there, because the guy who wrote these words owned hundreds of human beings and did not see the contradiction or hypocrisy of that.

There was an attempt to create this pseudo-science called eugenics, which postulated there was a hierarchy of races. At the top of which you could find a white Protestant Nordic races of Northern Europe. Aryans, Hitler would and did say. But there’s only one race, there’s only one race, Ed, and that’s the human race.

On the cover of “Our America” is a little Black boy. How would you describe America’s current racial moment?

I don’t know if I could characterize it. It’s always changing and always different, always moving forward, moving backward. Obviously, we felt since the murder of George Floyd, which was not a one-off occurrence — hundreds, thousands of African Americans have been murdered at the hands of policemen over the decades. But we are in a racial reckoning and at the same time we arrived in not just anti-Semitic, but other racist tropes and that’s quite a disturbing trend.

The choices of these photographs are not to speak to this moment, they’re to speak to all of American history. And that particular photograph is one of my most favorite of all time. It was taken by my mentor, Jerome Liebling, who taught me at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, a wildly wonderful, experimental school that’s still thriving and bringing in incredibly new and curious students every year.

It was a way to honor him but it was also a way to say, “You know that photograph of Abraham Lincoln in the book, the last photograph taken of him, the most beautiful photograph with a face that seems to have seen what these United States had been through before and were going through at that moment near the very end of the Civil War, and in some ways where it was going, it’s a singularly beautiful photograph, by Alexander Gardner. Yet, I’d say that in America, the ideal America, the 16th president is equal to this anonymous kid on the streets of New York whose soles are flapping and tied together with knots with laces that are broken a few times. At that moment they’re equals. You don’t get a photograph like that if you feel somehow above or perhaps below your subject in any way. It’s a marvelous reflection on our potentiality as a people, as a country, as a republic, as well as a way for me to honor this most significant of teachers in my life.

There is a lot of talk in today’s public discourse about “Critical Race Theory”and school boards and legislatures banning books. Have your works been subject to these controversies or threats of censorship?

Not overtly. I don’t know what “Critical Race Theory” is. I believe it’s a graduate legal studies thing. It means race is there. I’m in the storytelling business. I’m not in the theoretical expository business. I’m disappointed in a country with a First Amendment as its first amendment that there would be any sort of notion not just of banning things, but of sanitizing it. If you’re exceptional, as the United States keeps telling itself and the world, you have to be more critical of yourself. The novelist Richard Powers said: “The best arguments in the world won’t change a single person’s point of view. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” And I’m trying the best I can to tell this story.

Do you think of yourself as an activist? A spectator? An observer?

An observer and because you’re trying to make something, it’s storytelling. Storytelling is an active way of editing human experience and we try awfully hard to not put our thumb on the scale with regard to our own political beliefs for things. The films are an attempt to share the complexities. I have in my editing room a neon sign in lowercase cursive that says: “It’s complicated.” It’s there to just remind all of us that that scene you think is working perfectly, one day we’re going to find contradictory evidence. And we’re going to have to change it. And you have to be ready to change it. Even if it makes it a less perfect scene.

I.F. Stone said: “History is not a melodrama, it’s a tragedy.” And it is — none of us get out of it alive. I think what he means is that in melodrama, every villain is perfectly villainous, every hero is perfectly virtuous. That’s not the way it works out. In life, the hero has scenes to play and the villain has interesting human aspects. So, it behooves us to tell interesting stories. That’s why I resist the “warts and all,” because it seems to just favor that it will bring up negative stuff. The book is a series of photographs that in their totality are wonderfully joyous and at the same time it’s sobering because, yup, this is who we are, too.

Do you aspire for your storytelling to be transformational?

Yes, but I don’t want to prescribe it. I don’t want to say: “This is what your response should be.” If Richard Powers is right, and the only thing that can change a person’s mind is a good story and not an argument, what you do is you tell a good story, not knowing how it will be received with you or somebody else. So, maybe a film is transformational? Like the people who got up off of their couches after the Civil War and went and visited battlefields. Many kids at that time were so influenced that they went into history and were teachers or professors. That’s transformational.

By working largely with PBS, which is in part government-funded, have you encountered constraints?

PBS is not U.S. government-funded. Fewer than 18% of PBS’ money comes from the federal government. That comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which I do get funds from. I have never run into any instances of that. I enjoy a good relationship with people on both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill. I’m often called to testify on behalf of continuing funding for the National Endowment for the Humanities and Arts and for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. I wholly believe in it and all of my films have gone out on PBS. Not just that there’s no commercials, that’s kind of obvious, but because they give me the time to do it.

I can walk into a premium cable place or a streaming service with my track record and say: “I want to make a film on the Vietnam War,” and they’d say “Great!” And, “I need $30 million,” and they’d say “fine.” In one day, I could walk out with that, instead of spending seven years fundraising for the Vietnam series. But what they wouldn’t give me is the creative freedom I enjoy, and more important, the time it took. It took Lynn Novick and I and our team 10 and a half years to make that series on the Vietnam War… Nobody’s peering over our shoulders, tapping their feet, saying: “Ooh, don’t make it this way, don’t make it that way.” So, that creative control has meant everything, and the time, the ability to incubate these projects is just a godsend.

To paraphrase a Zen kōan about a tree falling in the forest: If a historical event occurred but nobody remembers and/or discusses it, did the incident really happen?

Yeah, that’s an interesting question. This has a human arrogance to it. Of course, it made a sound. If there was a bird nearby it would flutter away. What we’re talking about is the way in which parts of the past can get lost, and do, often. It’s not so much — there’s always a witness to something that happens. It’s just a question of whether you’re favoring those kinds of witnesses. Each generation rediscovers and reimagines that kind of path that makes their present more understandable. Almost every film I’ve made rhymes, echoes, resonates in some way with what’s going on right now.

Who is in the last photo of “Our America” and why?

One day Susie came excited and said: “Look at this!” I knew John Lewis for decades, I admired him, he was a hero of mine. I spoke with him every year. It’s a beautiful picture of him in repose. It was a way to honor him and the sense of how much work there is still to do and how much work has been done. This book is a mirror.

What’s next?

We’ve got everything planned out over this decade. Several films on the American buffalo, our first non-American topic on Leonardo Da Vinci. I spent all this week working on a big series of the history of the American Revolution. We’re doing something on the history of Reconstruction called “Emancipation to Exodus.” We’ve got a film halfway written on the history of LBJ and the Great Society. That takes us through most of the decade.

If I was given 1,000 years, which I will not be given, I would not run out of topics.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.