Why Do We Care So Much About the Supreme Court?

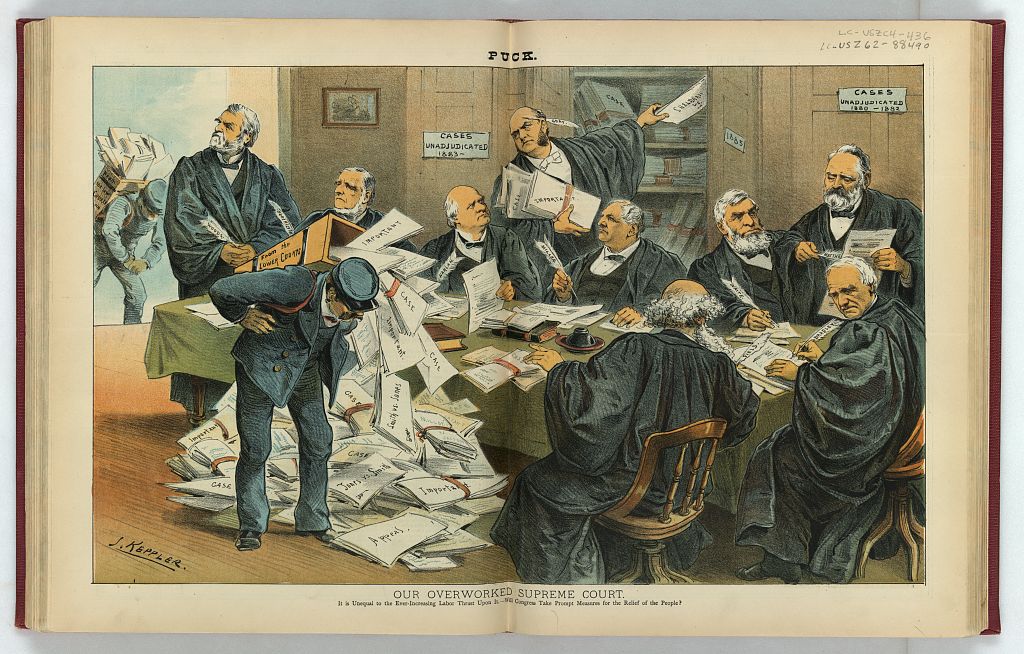

It is not a new phenomenon. Americans have always cared passionately about the Supreme Court. Keppler, J. F. (1885) Our overworked Supreme Court / J. Keppler. , 1885. N.Y.: Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann, December 9. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

This is Part of the "The Supreme Court’s War on the Future" Dig series

Keppler, J. F. (1885) Our overworked Supreme Court / J. Keppler. , 1885. N.Y.: Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann, December 9. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

This is Part of the "The Supreme Court’s War on the Future" Dig series

–“There is virtually no political question in the United States that does not sooner or later resolve itself into a judicial question.” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835).

Each October, as the Supreme Court begins another another term, academics, politicians and media pundits across the ideological spectrum engage in an annual ritual, probing and profiling the most significant cases pending before the court, and attempting to predict how they will be decided. The October 2022 term is no different.

In its current session, the court is considering critical cases on affiramtive action, LGBTQ rights, voting rights and an obscure doctrine known as the “independent state legislature” doctrine, which, in its extreme form, would allow state legislatures to determine the outcome of federal elections without regard to the popular vote. At BlumsLaw.com, Truthdig.com and elsewhere, I follow the biggest cases from the briefing stages to the oral arguments the court holds in open session to the day final decisions are rendered at the end of June. I follow the cases because I care deeply about the Supreme Court and the huge impact it has on every aspect of our civic life.

And I am not alone.

Americans have always cared deeply and passionately about the exercise of judicial power, dating back to colonial times. Legal disputes over taxation, the issuance of general search warrants known as writs of assistance and expansions in the jurisdiction of the King’s dreaded Vice Admiralty Courts were key factors in sparking the American Revolution.

No less than three of the 27 grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence concerned the administration of justice. The signers of the declaration complained that George III had deprived them of the right to establish their own courts, that he had made judges dependent on him for their salaries and tenures, and that he had deprived them of the right to trial by jury.

The Articles of Confederation, our first national charter, marked the end of British rule, but did not create a national court system. The administration of justice was left largely to the states, which were free to disregard acts of Congress. It was not until the ratification of the Constitution in 1789 that a separate judicial branch of government was established to operate alongside Congress and a newly created executive branch headed by the president.

The Supreme Court is the only federal court explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. The Constitution grants Congress the authority to establish lower federal courts. Today, there are 94 district and 13 federal circuit courts of appeals. There are also specialized federal courts that deal with specific issues, such as veterans’ claims (United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims) and military matters (United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces).

Sitting atop them all is the Supreme Court, which has the ultimate authority to decide appeals on all cases brought in federal or state courts dealing with issues of constitutional law. The Supreme Court, as de Tocqueville long ago observed, passes judgment on issues that touch all of our lives, dealing with everything from voting rights and abortion to the Second Amendment, presidential power, campaign finance regulations and the death penalty. It’s little wonder, then, that we care so deeply about the court and the far-reaching authority it wields.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.