Ignoring the Other Victims of 9/11

When the National Guard helicoptered her husband, Mark, to Staten Island to work as a wireless technician setting up a communications network for thousands of emergency workers who were descending upon Lower Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001, Jeanmarie DeBiase did not know this would begin the unraveling.WASHINGTON — When the National Guard helicoptered her husband, Mark, to Staten Island to work as a wireless technician setting up a communications network for thousands of emergency workers who were descending upon Lower Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001, Jeanmarie DeBiase did not know this would begin the unraveling.

She would not realize it until Jan. 8, 2006 — her birthday — when, during a family celebration, Mark broke down in tears.

“He sat at my dining room table crying that there was something wrong, that he didn’t want to die,” DeBiase recalled in an interview from her home in Jackson, N.J. Her husband, who worked at the landfill where debris from the fallen World Trade Center was dumped, had suffered a cold for a few days — nothing serious, it seemed. He was a vigorous man of 41, an exercise aficionado who was so careful about his diet that his wife packed his lunch every day. Yet that night at dinner, he sobbed that he wanted to watch his young sons grow up, to play ball with them, to know his grandchildren.

The initial diagnosis was pneumonia, but Mark failed to respond to antibiotics; lung X-rays could not confirm any diagnosis at all. “There was so much stuff in his lungs I don’t think they could pinpoint anything,” Jeanmarie says. “They really didn’t know how to treat it.” Visits to the prestigious Deborah Heart and Lung Center did not bring hope. Mark DeBiase died on April 9, 2006, in Philadelphia, while awaiting a double lung transplant.

“A lot more illness and death is going to come out of this,” says his widow, who is supporting her three sons on about $3,400 a month in Social Security survivors’ benefits. Health insurance, still provided by Mark’s employer, the wireless company Cingular, cost $64 a month during the first year after her husband’s death. In May, the monthly premium rose to $394.

DeBiase considers herself fortunate — she has supportive family and friends, and access to health insurance. She has filed a worker’s compensation claim under a New York state program for workers who were consistently exposed to health hazards in the days and months after the Twin Towers collapsed in a poisonous concoction of dust, burning fuel, chemicals and metals. The contents and lethality of the toxic stew still aren’t entirely known.

Typically, employers fight the claims, lawyers say. And typically, a claim takes one to two years to wind through the bureaucracy.

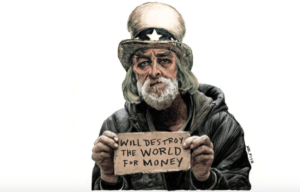

The country says it will always remember 9/11. Few politicians miss the chance to appear at this or that commemorative service.

Perhaps it is true we have not forgotten those who died that day. But we have abandoned those who are dying now.

Thousands of construction workers, janitors, communications specialists, food-cart vendors and others who worked amid the noxious fumes for weeks or months — removing debris not only from Ground Zero but from the office buildings that still stood, reviving communications, feeding and providing aid to those who toiled — are sick with lung disease and all manner of rare cancers, according to various health officials. An expert panel created by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg concluded that as many as 410,000 people faced sufficient exposure to health hazards that they could become ill.

About 59 percent of those screened at a city center for patients suffering from World Trade Center-related illnesses are uninsured. The majority have incomes of less than $15,000 a year. Even at a screening center run by Mount Sinai Medical Center for “first responders” — an elite group among those who are turning up sick — an estimated 40 percent lack insurance.

New York politicians have persistently pursued more federal involvement and funding. The federal government has perennially rebuffed them.

Here is one measure: After federal health authorities involved in monitoring and treatment of World Trade Center emergency responders estimated they would need $283 million a year to run the program, President Bush’s budget allocated $25 million.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler, D-N.Y., whose district encompasses Ground Zero, and other New York lawmakers used the sixth anniversary of the attack to introduce legislation to require health monitoring and care for all those who are sick from exposure to what may be the most serious environmental catastrophe in the nation’s history. Yes, it would be an “entitlement.” And yes, it would be costly — certainly more expensive than a ribbon of remembrance.

It would, at last, require the country to come to grips with the knowledge that the official toll of 2,750 from the World Trade Center attack isn’t the final death count. It’s only the first.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.