Evelyn Waugh’s Life Revisited

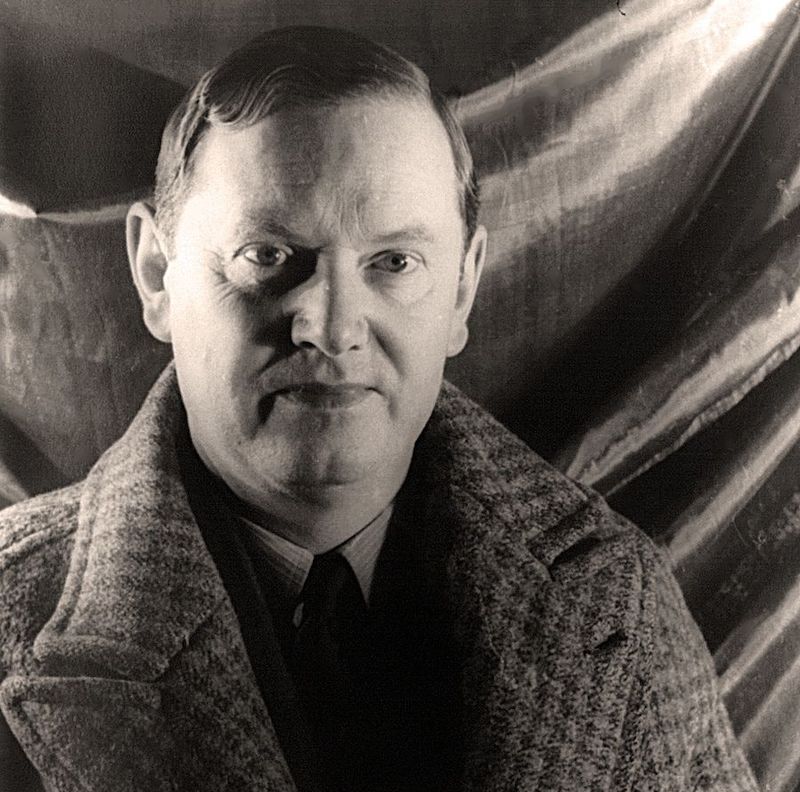

The British writer hailed "from plenty of useless lords," per his biographer. Luckily, his novels will likely outlive his biographies. Evelyn Waugh in 1940. (Library of Congress)

Evelyn Waugh in 1940. (Library of Congress)

“Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited”

A book by Philip Eade

Nearly every one of Evelyn Waugh’s novels is either in print or easy to find (Oxford University Press has published Volume 26 in a 43-volume complete works), and every few years there’s another TV series or feature film based on one of them. Biographies and memoirs by friends and family members fill a library shelf. And yet, he belongs to that strange handful of writers—Graham Greene is another—who was never entirely in vogue but has never gone out of fashion.

In the era of graphic novels and e-books, Waugh seems to be as much read as he ever was, even if only for “The Loved One” and “Brideshead Revisited,” two books that he regarded as atypical of his oeuvre. There is no question that Waugh carved out his own niche in English literature, one that extends beyond tweed-wearing Americans who sip sherry at the Dartmouth Club to people like Anna Faris’ airheaded starlet in the 2003 film “Lost in Translation,” who checks into a Tokyo hotel under the name “Evelyn Waugh” (she pronounces it like the common female name, “EV-a-lin,” with a short E).

For four decades, from the publication of “Decline and Fall” in 1925 to his death 40 years later, it’s hard to find an English-language novelist who drew rave reviews from critics of all stripes. In a famous 1944 piece, Edmund Wilson, who surely despised every social value that Waugh stood for, called him “The only first-rate comic genius that has appeared in English since Bernard Shaw.”

Jean-Paul Sartre, of all people, praised Waugh as one of the progenitors of “the anti-novel.” Clive James, the greatest critic of our own time, thinks him “the supreme writer of English prose in the 20th century”—even though “so many of the wrong people said so,” by which, presumably, he meant cultural conservatives who thought that Waugh’s politics kept him from winning the Nobel Prize. Perhaps, but Waugh has continued to be read while the work of many a Nobel Prize winner has faded into the twilight realm of the praised but unread.

Did any great novelist of the 20th century lead a more boring life than Evelyn Waugh? Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh was born Oct. 28, 1903, to middle class parents descended, according to his latest and most fastidious biographer, Philip Eade, in “Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited,” “from plenty of useless lords.” Waugh once told a friend, Eade writes, “that he would have far sooner have been descended from a useless Lord, by which he meant a hereditary peer, than from one ennobled for practical reasons”—as perfect a definition of snobbery as I can think of. (If you’re interested, there are four pages of Waugh’s ancestry just before the first chapter.)

Beginning with Evelyn’s father, Arthur, the clan has produced over 180 books. Members of the family also produced Waugh’s Curry Powder, Waugh’s Lavender Spike (an ointment for aches and pains), and Waugh’s Family Antibilious Pills (much favored by Queen Victoria).

Click here to read long excerpts from “Evelyn Waugh” at Google Books.

Eade’s aim seems to be to counter the opinion that Waugh was an ill-tempered snob, but this book provides much evidence that the detractors were right. Eade quotes Waugh from his own autobiography: at Eton, “I simply longed to remain myself, and yet be accepted as one of this distasteful mob.” At Lancing, a schoolmate thought that he was “courageous and witty and clever but was also an exhibitionist with a cruel nature that cared nothing about humiliating his companions. …”

There is much argument back and forth as to whether or not Waugh was a homosexual during his school days. I think the poet John Betjeman settled the issue once and for all—“Everyone was queer at Oxford in those days!”

As for the lingering accusations of racism, “It is commonplace to accuse Evelyn of being racist in his diary entries.” Here’s a story that you can judge for yourself. Waugh recorded in his journals that he and a friend called on Florence Mills “and other niggers and negresses in their dressing rooms. Then to a nightclub called Victor’s to see another nigger—[the American cabaret star] Leslie Hutchinson.”

There are numerous other passages like this in “A Life Revisited.” The best that one can say for these passages is that if they don’t reveal racism, they certainly reflect a deep-seated condescension toward those not of Waugh’s race or class—and yet, if that isn’t racism, what is?

When his father asked him how he could be “so charming to his friends and yet so unkind to his father,” Waugh replied, “Because I can choose my friends, but I cannot choose my father.” He wasn’t always that kind toward his friends. David Niven, as amiable a soul as the acting profession ever produced, did not take kindly to Waugh’s referring to his black housekeeper, in her presence, as “your native bearer.” Where is the line between racist and simply rude? When approached by the photographer and artist Cecil Beaton at a party, Waugh exclaimed, “Here’s someone who can tell us all about buggery!” The best that can be said in Waugh’s defense is that he was almost certainly drunk.

Waugh’s bigotry was boundless. On Americans: “It is very degrading to be constantly in the company of people you have to ‘make allowances for.’ ” Some Americans returned the sentiment: Hollywood screenwriter Charles Brackett described the Waughs as “a bank clerk and his snuffy wife, an ill-favored tailor’s dummy.”

Hemingway’s third wife, writer Martha Gellhorn, was less polite. She called Waugh “a small and very ugly turd.”

If you want to cut Waugh some slack for getting good reviews as a parent from some of his children, you must counter it with a comment by Arthur Waugh in a letter to Evelyn’s brother, Alec, after Evelyn and his wife, Laura, lost a baby girl shortly after the child’s birth: “She wasn’t wanted and she did not stay.”

How much of this is mitigated by Waugh’s apparently sincere Catholicism? Even some of Waugh’s friends conceded that “Brideshead Revisited” contained “too much Catholic stuff.” In one of the meanest and most accurate criticisms made of “Brideshead Revisited,” Edmund Wilson wrote in The New Yorker that “Waugh’s snobbery, hitherto held in check by his satirical point of view, has here emerged shameless and rampant. … His cult of high nobility is allowed to become so rapturous and solemn that it finally gives the impression of being the only real religion in the book.”

In a 1973 essay, Wilfrid Sheed, a devout Catholic himself, wrote that Waugh “admired the aristocrats he couldn’t reach, a class that is really too good for him—even if he had to invent it, as he did in ‘Brideshead Revisited.’ ” Sheed’s comment raises the question as to whether by converting to Catholicism, Waugh was simply trying to raise himself to a more exclusive social level (apparently there were few poor Catholics in England).

There are several intriguing facets of Waugh’s life that I would like to know about and understand better. One is his friendship with Graham Greene, a man whose political views were so different from his—Greene, though only briefly, was a member of the Communist Party and had a lifelong allegiance to it—that he almost seems to have been spawned on a different planet from Waugh. They had only their conversion to Catholicism to keep them friendly, yet their relationship endured. (Greene wrote lovingly of both “Brideshead” and Waugh’s biography of the 16th century martyr and saint Edmund Campion.) But Eade mentions Greene just a few times and never really examines the issue of whether or not the friendship was strained over politics.

Another fascinating aspect of Waugh’s life is his kindness, late in life, to George Orwell before the author of “1984” died of tuberculosis in 1950. It’s fascinating to think that the classic conservative visited and wrote letters to the unapologetic socialist—two men so different that it’s hard to imagine one passing the salt to the other at the dinner table. (John Le Carré, who taught at Eton, found it amusing that Orwell, who had attended the school, went well out of his way to disown the place while Waugh, who didn’t go there, often pretended that he had.) Waugh was sympathetic to the Fascists while Orwell fought for the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War.

Why were they simpatico? Certainly Waugh was grateful that Orwell, in the pages of the Times Literary Supplement, defended “Brideshead Revisited” from left-wing attacks. The subject of their relationship was treated at length in a 2008 book, “The Same Man: George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh in Love and War” by David Lebedoff, but not at all by Eade in “A Life Revisited.”

Few of what might be called the larger issues of Waugh’s life are addressed here. Waugh’s WWII experiences are treated at length, but we’re told little about the conflict’s effect on Waugh except that “The war had been frustrating and disillusioning for Evelyn.” Well, I read somewhere that it had been bad for somebody. That sums up World War II.

We’re really not even told how Waugh’s well-known conservatism affected his writing, except that he wrote in his diaries that he “didn’t want to influence opinions or events or expose humbug or anything of that kind. I don’t want to be of service to anyone or anything. I simply want to do my work as an artist.” Which is exactly what? I wish Eade had delved into Waugh’s magnificent satires, which exposed “humbug” no matter what Waugh thought.

Eade writes, “This is not a ‘critical’ biography in the sense that it does not seek to reassess Evelyn Waugh’s achievements as a writer. …” That’s a shame. I could have done with fewer stories of Lady Pansy Pakenham, Pixie Marix and Godfrey Wildman-Lushington. The anecdotes are amusing, but would count for nothing if Waugh hadn’t been a great writer. I still long for more insights into his work, especially “A Handful of Dust and Scoop.” Luckily for Waugh, his novels will probably outlive his biographies.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.