Jacksonland

Everyone knows, or should know, about the Cherokee Trail of Tears in the early 1830s. But not till now, with NPR journalist Steve Inskeep's new book focusing on President Andrew Jackson and Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross, has this episode in American history been rendered in such personal and human detail. Penguin Press

Penguin Press

Penguin Press

|

To see long excerpts from “Jacksonland” at Google Books, click here. |

“Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab” A book by Steve Inskeep

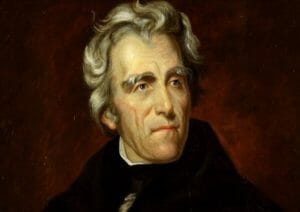

Surely everyone knows, or should know, about the Cherokee Trail of Tears — an ordeal imposed upon thousands of Cherokees, who, after fighting and winning a judgment in the Supreme Court against their removal from the Eastern Seaboard, were nonetheless dispossessed of their tribal lands and marched to Indian Territory in the early 1830s. The scale of the removal was staggering. Not only the Cherokee but also the Muskogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and many of their African-American slaves were removed in one of the largest and most brutal acts of aggression ever committed by the United States. But not till now, with the coming of NPR journalist Steve Inskeep’s magnificent book, focusing as it does on the two key players — President Andrew Jackson and Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross — has this episode in American history been rendered in such personal detail and human touch.

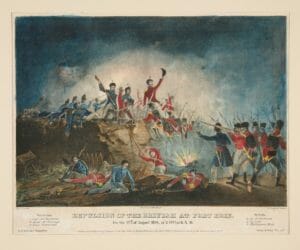

Inskeep begins his tale of dispossession in earnest at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. By that time Jackson was already famous for his modest origins, his politics and his victory over the British at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. It was at Horseshoe Bend, in what is now Alabama, that what could be called the “war of settlement” truly began, when the U.S. military and its Indian allies attacked and demolished the Creek “Red Stick” separatists. And it was at Horseshoe Bend that John Ross — a young Cherokee statesman and fighter — fought for and became acquainted with Jackson. The two men’s destinies became linked during the battle, and they remained linked through their long struggle for control of the American Southeast. What Inskeep shows us — through letters, first-rate historical research, and able prose — is how the Cherokee (dispossessors and colonists of other neighboring tribes like the Creek and Catawba and Tuscarora) fought for the United States and then, after their destinies were intertwined, ended up fighting against the government, in court and through lobbyists and by any other means except outright warfare. What emerges from the story of the two men is a bigger portrait of power and conflict in early America, which wasn’t simply a matter of white transgression and Indian resistance. Rather, Indians and whites were sometimes allies, sometimes not, sometimes united in cause, sometimes not. And the map of power wasn’t simply federal-versus-tribal. There was a complex web of relationships between Indian tribes, the federal government, and states (like Georgia) that wanted to dictate state sovereignty on their own terms.

More than that, Inskeep — by focusing tightly on the public and private movements of the two antagonists and keeping his story confined to the events leading up to removal rather than on the hardships of the removal itself — shows us that the Indians Wars in the latter part of the 19th century (what could be called the War of the West) really began in the East; the Cherokee Removal marked the end of a policy of diplomacy and negotiation between the tribes and the United States and ushered in a vast and bloody period that touched tribes from the Plains to California. We can also see that the Civil War in some ways began in the 1830s over issues of sovereignty and control, and that at the bottom of all of it was a deep, almost insatiable quest for land.

Perhaps no American president was more rapacious than Andrew Jackson. After the War of 1812, as a colonel in the U.S. Army responsible for fighting Indians in the Southeastern United States, he used his military conquests to buy huge tracts of land in Alabama and Tennessee for himself and his business partners. After “liberating” millions of acres of Indian land and bringing it into settlement, he used his government status to position himself and his friends as first in line at land auctions, to hire his friends as surveyors, and to make side deals with tribal leaders (complete with doceurs — sweeteners, that is, bribes — to have some of the best parcels set aside for himself). Inskeep explains this kind of unseemly, if not illegal, dealing diplomatically: “In his abiding interest in land, Andrew Jackson was a reflection of his country as well as his time. The settlement of land quite literally underlay the entire project of building the United States. But Jackson’s acute sensitivity to rumors about his real estate business revealed another layer to the story. While the speculator was not necessarily immoral or corrupt … speculation was a morally fraught enterprise.” But perhaps Inskeep is a little too diplomatic. While Jackson was, of course, a man of his time and culture, not all men were like Jackson. There were many others, inside and outside government, who deplored his greed and violence. Even by the measure of his time, he was a self-serving, greedy and immoral speculator who casually disposed of his Indian allies and friends in order to increase his own market share.

As for Ross, his story is painful to read. We meet him in full flower: young, bilingual, articulate, literate. He has done everything asked of him by the U.S. government, and he expects the United States, and Jackson, to honor the sacrifices of his people. By degrees, his faith is undone. Yet still — by visiting Washington, lobbying lawmakers, funding the first Cherokee newspaper out of his own pocket — he fights for his people with words, and he loses by force. After taking his fight to the courts and winning a victory against removal in the Supreme Court, he is rebuffed by then-President Jackson, who allegedly says: “That’s their decision. Now let’s see them try to enforce it.” After that, the removal is unavoidable. So, too, is a major shift in federal Indian policy. Up till that point the U.S. government has dealt with tribes through — and often with — diplomacy. After that, the United States and tribes across the country slide inevitably toward open conflict that doesn’t end until the close of the century.

The story of the Cherokee removal has been told many times, but never before has a single book given us such a sense of how it happened and what it meant, not only for Indians, but also for the future and soul of America.

David Treuer’s most recent book is “Prudence,” a novel.

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.