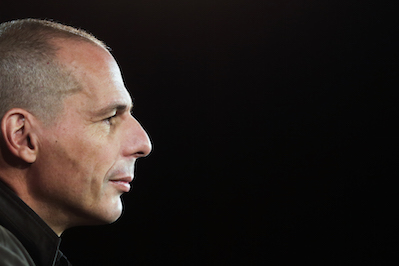

Yanis Varoufakis, Former Greek Finance Minister, Returns to Public Life More Hopeful Than Ever

The left-wing Syriza member resigned in 2015 after five tumultuous months battling eurozone creditors as they turned the austerity screws on Greece. Now he is continuing the fight through the new democracy movement, DiEM25. 1

2

1

2

Yanis Varoufakis: Solutions exist to make the eurozone “efficient and humane.” (Markus Schreiber / AP)

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.