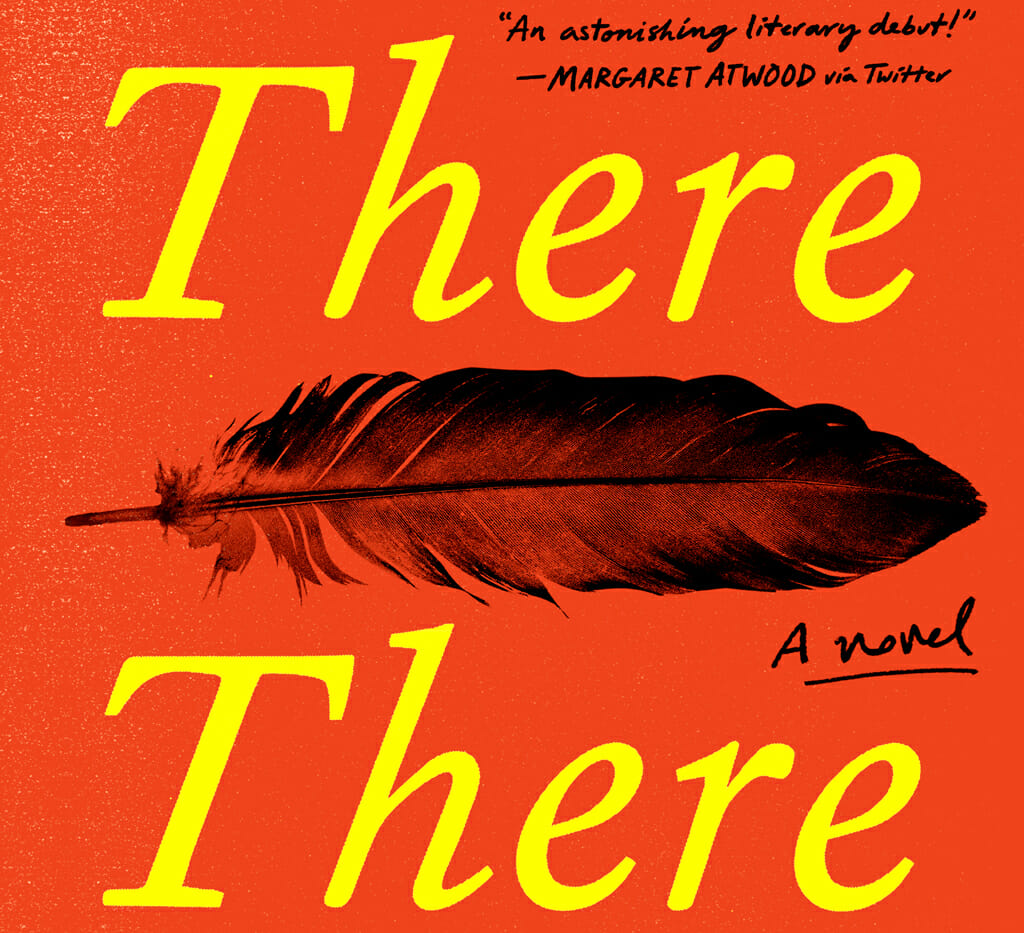

What Does It Mean to Be a Native American?

Tommy Orange's devastating debut novel offers a bracing answer. Knopf

Knopf

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

“There There”

A book by Tommy Orange

Toward the end of Tommy Orange’s devastating debut novel, a 4-year-old Native American boy keeps asking his grandma: “What are we? What are we?”

The boy has no way of knowing, but that’s a blood-soaked question that Western invaders have made Indians ask themselves for centuries. Exiled, dispersed, murdered, robbed, mocked, appropriated and erased, Native Americans have been forced to define themselves amid unrelenting assault. Their survival, their failure and their resilience in modern-day America are the subjects of “There There,” this complex knot of a novel by a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

Everything about “There There” acknowledges a brutal legacy of subjugation—and shatters it. Even the book’s challenging structure is a performance of determined resistance. This is a work of fiction, but Orange opens with a white-hot essay. With the glide of a masterful stand-up comic and the depth of a seasoned historian, Orange rifles through our national storehouse of atrocities and slurs, alluding to figures from Col. John Chivington to John Wayne. References that initially seem disjointed soon twine into a rope on which the beads of American hatred are strung. (Whoever is editing this year’s collection of “The Best American Essays,” please don’t pass over this prologue just because it’s in a novel.)

The story that follows comes to us in short, intense chapters that focus on different members of a large cast of Indians around Oakland, California. Some of these people speak to us directly; others are described in the third person, forming a collection of diverse approaches that may remind readers of Jennifer Egan’s “A Visit From the Goon Squad.”

Alcoholism, unemployment and depression conspire to thwart most of these characters’ lives. In varying degrees, their vague sense of ethnic pride is infected by a toxic germ of shame. There’s a young man born with fetal alcohol syndrome whose mother is in jail. Another man, “ambiguously nonwhite,” has won a grant to record the life stories of “Urban Indians,” asking each of them, “What does being Indian mean to you?” A third young man, overweight and constipated, has a graduate degree in Native American literature but no job prospects—a living symbol of the moribund plight of Indian culture in the United States.

One chapter, which appeared earlier this year in The New Yorker, is told in the second person and describes Thomas, an alcoholic who recently lost his job as a janitor. “One of these big, lumbering Indians,” Thomas feels permanently suspended between the world of his white mother and the world of his medicine-man dad who “is one-thousand-percent Indian.” “You were white, you were brown, you were red, you were dust,” the narrator says. “You were both and neither. When you took baths, you’d stare at your brown arms against your white legs in the water and wonder what they were doing together in the same body.” But despite that incurable confusion, Thomas feels a constant drumbeat, an irresistible rhythm that pounds into him a longing for his Native heritage: “You should probably have done something else with your fingers and toes than tap, with your mind and time than knock at all the surfaces in your life like you were looking for a way in.”

Orange makes little concession to distracted readers, but as the number of characters continues to grow—a trio of brothers, a postal worker, a girl who moves to Alcatraz with her family—we begin to grasp the web of connections between these people. And eventually their lives coalesce around an upcoming powwow in the Oakland Coliseum. But they have vastly different expectations for the celebration. For some, the powwow is an opportunity to honor a history they treasure; for others, it’s a chance to discover a heritage they know almost nothing about. And for a small band of thugs, it’s the perfect setup for a robbery.

The variety of their responses to the powwow—some deeply spiritual, others wholly amoral—demonstrates the diversity of a group of people too often lumped together under a wooden stereotype. But in almost every story, Orange notes a striving for self-knowledge, a secret desire to see oneself. Again and again, the characters study their faces in a mirror or a video or some passing reflective surface, hoping to perceive something beyond the image of uselessness and irrelevance that a racist nation insists upon.

In the most poignant instance, a 14-year-old boy named Orvil Red Feather sneaks into the bedroom of his grandmother, Opal, and puts on traditional Indian clothes. He’s thrilled but somehow disoriented, too, by seeing himself as an Indian dressed up like an Indian. “It isn’t backwards,” Orange writes, “and actually he doesn’t know what he did wrong, but it’s off. He moves in front of the mirror and his feathers shake. He catches the hesitation, the worry in his eyes, there in the mirror. He worries suddenly that Opal might come into the room, where Orvil is doing … what? There would be too much to explain.”

As these individual stories intersect, the plot accelerates until the novel explodes in a terrifying mess of violence. Technically, it’s a dazzling, cinematic climax played out in quick-cut, rotating points of view. But its greater impact is emotional: a final, sorrowful demonstration of the pathological effects of centuries of abuse and degradation.

Ron Charles is the editor of Book World at The Washington Post.

©2018 Washington Post Book World

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.