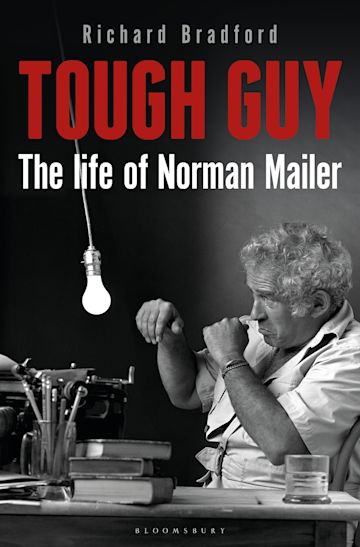

Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer

Whoever said that a biographer eventually comes around to admiring his subject never met Richard Bradford. Author Norman Mailer attends a lecture at the New York Public Library on June 27, 2007, in New York. (AP Photo/Diane Bondareff, File)

Author Norman Mailer attends a lecture at the New York Public Library on June 27, 2007, in New York. (AP Photo/Diane Bondareff, File)

The following is a review of “Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer” by Richard Bradford, published January 17, 2023 by Bloomsbury Caravel.

Norman Mailer’s achievement in American letters is unassailable. He somehow melded the heroic intensity of Ernest Hemingway with the French existentialist idea of determining one’s path through will, while still producing twelve novels and several works of nonfiction, a play and one volume of poetry, most of which are as devoid of literary and intellectual value as the “historical” novels of Bill O’Reilly.

Somebody – Ezra Pound, Octavio Paz, Oscar Wilde, I don’t know who but somebody – said that “literature is journalism that stays journalism.” But what about journalism that achieves the status of literature? Or stated more simply, does Norman Mailer’s literary journalism merit an enduring place in American literature?

I don’t know if people are still reading books by Mailer, but they certainly continue to read books about Mailer. The latest is “Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer” from British writer Richard Bradford, author of a much-discussed 2021 biography of Patricia Highsmith. “Tough Guy” contains not nearly as much biographical information as J. Michael Lennon’s “Norman Mailer: A Double Life” (2013), which is well over three times as long. But Bradford’s book has all the personal info you want to know; certainly, no one would want to read about any more drunken brawls, sober brawls, psychotic threats, nasty feuds, wife beatings (“I like to marry women I can beat once in a while”) or failed marriages. Norman was married six times, and I swear to God, if I had to read about one more bad marriage I would have closed the book.

There’s an adage to the effect that a biographer eventually comes around to admiring his subject. Whoever said that never met Richard Bradford.

Every insult directed to another writer is meticulously preserved:

— J.D Salinger, “The greatest mind ever to stay in prep school.”

— Gore Vidal “is imprisoned in the recessive nuances of narcissistic explorations which do not go deep enough into himself, and so end as gestures and postures.”

— Saul Bellow, “I cannot take him seriously as a major novelist.”

— Of women writers who were his contemporaries, “I do not seem able to read them … the sniffs I get from the ink of the women are always fey, old-hat, Quaintsy Goisy, tiny, too dykily psychotic, crippled, creepish, fashionable, frigid …”

— Evelyn Waugh, “I hate to admit it, but the little fairy can write.”

“Indeed,” writes Bradford, “it seemed almost an insult not to be insulted by Mailer.”

Insulting other writers was the least of Mailer’s character flaws: “During the 1940s and ’50s, Mailer was outspokenly homophobic, and even when he later came to regard gay people as figures who should be free to follow their inclinations, he harbored a residual sense of homosexuality as a choice, which he respected mainly because of its ‘perversity.’”

Of women in general: “Low, sloppy beasts.”

In a frenzy from some insults real or imagined, he made headlines when he stabbed his second wife Adele at a party at the Mailers’ apartment and later in the hospital told her he had to do it because, “I love you, and I had to save you from cancer.” (“Cancer,” says Bradford, “was used by Mailer as a synonym for just about any “moral or political degradation.”

Norman Mailer, Bradford writes, “seemed to be living in a world unconstrained by notions of responsibility accepted by the rest of society.”

He regularly assaulted editors and writers with whom he had fallen out. One, after a famous on-screen clash with Gore Vidal on “The Dick Cavett Show,” Mailer pushed Vidal to the floor only to have Gore win the altercation for posterity by saying, “Well, Norman, once again words fail you.”

Norman Mailer, Bradford writes, “seemed to be living in a world unconstrained by notions of responsibility accepted by the rest of society.” It was a condition he infected others with. In Provincetown, Massachusetts, while working on one of his vanity movie projects, “Maidstone,” he harangued actor Rip Torn to put more method into his role as an assassin. Torn got so worked up he attacked Mailer with a hammer; Mailer fought him off, then bit off part of Torn’s ear. Torn would later explain his mindset at the time of the attack: “Norman must have told 20 or 30 people to set up an assassination attempt, because the film was supposed to be about assassination…I thought I was doing it for the film.”

Torn was not charged, but if he had been, says Bradford, “He would probably have been the first person to be found not guilty by reasons of postmodernism.”

* * *

Norman Kingsley Mailer was born on Jan. 31, 1923, in Long Branch, New Jersey; it must have tickled him no end that his father Barney had immigrated from South Africa and had not applied for American citizenship when he married, meaning he and Norman were technically British citizens.

He grew up in Brooklyn, where “few other areas of the broader region of New York City or even the United States as a whole could merit comparison … as a hub for national, economic and racial diversity.” Nachum Melech, his Hebrew name – Melech means king – had a reasonably happy childhood. He was close to his parents, and he and his sister were well treated and the center of their parents’ universe. Consequently, his own childhood never interested him much, and he never wrote about it.

Between the 1950s to his death in 2007, Mailer wasted awesome talent and energy on writing fiction. His obsession with being the American Tolstoy – or at the least, Hemingway — resulted in a long shelf of unreadable books.

He was a brilliant student at Boys High in Brooklyn and read voraciously, including the wonderful potboilers of Rafael Sabatini, author of “Captain Blood” and the immortal “Scaramouche.” At 16, he was admitted to Harvard where, “For once, the Jews were not particular victims of discrimination. They were involved in an egalitarian culture of tribal abomination.” (“Mailer,” Bradford shrewdly observes, “treated antisemitism as a badge of honour, one of the proofs that the Land of the Free was in truth the enclave of the prejudiced.”) He majored in engineering and took writing classes as electives.

He wrote his mother a letter that said, “It’s all happening too easy.” Fanny Mailer preserved it in a scrapbook with other memorabilia of her son’s accomplishments.

Then came the war. By 1944 Mailer was a Harvard graduate and had married his first wife, Bea, and with his major in engineering, could have obtained a commission as an officer. (That and his 166 IQ score.) Apparently wanting to observe the Army and the war from the inside, like Sgt. Warren, the character played by Burt Lancaster in the film of James Jones’ “From Here to Eternity,” Mailer hated officers and enlisted as a private in the infantry: “I had the holy sense of importance that a GI has.”

Though it’s mostly forgotten now, the goal of many writers was to write the Great American War Novel. James Jones probably won the unofficial title in 1951, though “From Here to Eternity” was actually a pre-war novel. Mailer’s brief experience in the Pacific inspired his entry into the competition with “The Naked and the Dead,” published in 1948. Norman was a bit diffident about the book’s rave reviews and huge sales, probably because he thought its writing and structure was too conventional. But the book was the launching pad for a spectacular literary career and helped Mailer coast through the next decade during which he scarcely produced another first-rate work.

“Mailer’s most celebrated works,” argues Bradford, “were non-fiction books about real people and events in which he allowed himself the inventive license of a novelist, pretending to seriousness while making things up as he went along.”

Between the 1950s to his death in 2007, Mailer wasted awesome talent and energy on writing fiction. His obsession with being the American Tolstoy – or at the least, Hemingway — resulted in a long shelf of unreadable books. Who but a biographer is going to go back and mine “Barbary Shore,” “The Deer Park” (of which Marilyn Monroe offered the most astute observation that she felt Mailer was “too impressed by power”), “Why Are We In Vietnam?,” “An American Dream,” “Ancient Evenings,” “Harlot’s Ghost,” “Oswald’s Tale: An American Mystery,” “The Gospel According to the Son,” “The Castle in the Forest” and a few more misfires and miscalculations for even the tiniest shards of value. The longest of those are bloated misshapen monstrosities that apparently none of Mailer’s close friends and family had the nerve to talk him out of writing. (I’m leaving off that list Mailer’s 1984 crime novel, “Tough Guys Don’t Dance,” which I have an irrational fondness for.)

“Mailer’s most celebrated works,” argues Bradford, “were non-fiction books about real people and events in which he allowed himself the inventive license of a novelist, pretending to seriousness while making things up as he went along.”

It’s hard not to agree. Any reader who fights through the sludge of the many thousands of pages of his novels will surely find that “The Executioner’s Song” – about Gary Gilmore, the convicted murderer who became internationally famous for demanding that his death sentence be carried out – is Mailer’s only fiction that will survive the test of time (It was awarded the 1979 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was a finalist for the National Book Award). A controversy boiled up over whether “The Executioner’s Song” was fiction or fact: “At no point in the work,” Bradford writes, “[do] the events described amount to anything other than fully documented facts.” Most reviewers “treated it as a literary cross-breed: real life transported into something that reads like a novel.”

Much of Mailer’s life and work was filled with bluster and sham. Pauline Kael, who attacked him in print, was on the money when she said that “Mailer’s instinct is famous because it’s so often wrong.” Bradford’s assessment of Mailer, the man and the thinker, is merciless: “a shifty literary narcissist,” Mailer’s concept of the hipster was “a lazy hedonistic version of anarchism…a smokescreen for vileness,” he never “really understood far-left ideology” but was “addicted to its social vogueishness.” (For that matter, Mailer never really understood philosophy either. As Gore Vidal famously quipped, “Norman uses existentialism like a truck driver uses ketchup.”)

So, will Norman Mailer’s journalism stay journalism? Yes, I think, much of it. A new path was lit for journalism with “The Armies of the Night: The Novel as History – History as a Novel,” his account of the 1967 march on the Pentagon, which was a landmark in American letters (it was awarded both the Pulitzer and the National Book Award). That same year saw the publication of his great accounts of the Republican and Democratic conventions, “Miami and the Siege of Chicago,” which captured a pivotal moment in American political history. His book-length account of the moon landing, “Of a Fire on the Moon,” is definitive (that degree in engineering finally paid off). “Marilyn: A Novel Biography,” his fan-fiction mash note to Monroe, is the ultimate piece of fan fiction, and “The Fight,” his report of the epic 1974 Rumble in the Jungle between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, may be the most exciting piece of sportswriting ever written. And for those in the future who want to step into the maelstrom of American politics in the 1950s,’60s and ’70s can dip into the essays of “Advertisements for Myself, Cannibals and Christians,” and, with apologies to Gore Vidal, “Existential Errands.”

That’s journalism that will stay literature.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.