Wes Anderson’s Age of Anxieties

In “Asteroid City,” flying saucers and mushroom clouds cast shadows over the auteur’s signature palette. Scarlett Johansson surveys a postwar desert landscape defined by anxiety. Image: Focus Features.

Scarlett Johansson surveys a postwar desert landscape defined by anxiety. Image: Focus Features.

Despite numerous attempts by A.I.-wielding satirists, Wes Anderson remains the only person capable of generating something unique from the data set of his filmography. Where Anderson-inspired TikTok trends and A.I. imitations merely skim the colorful surface, the director’s own remixes draw from a deeper well of influences — Satyajit Ray, Kurosawa Akira, the French New Wave — resulting in films that are characteristically reverential towards the past, while pushing the evolution of his moviemaking. “Asteroid City” is the latest star-studded ensemble piece in this vein, a fresh spectacle of Spielbergian dimensions that wears its influences on its sleeve and brims with the lo-fi delights of 1950s science fiction.

The story follows several families whose teenage children have been selected for a 1950s Junior Stargazer convention near a New Mexico nuclear testing site. Though Anderson deploys a handful of his usual flourishes, his signature pastels are more muted and his fluid camera can’t quite seem to land on its subjects at the right moment; it pans across wide open desert spaces as if searching for answers. This stylistic imbalance goes hand in hand with the movie’s unstable emotional core: a middle-aged father, August “Augie” Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), must break the news to his teen son and preteen daughters that their mother has died, while also finding the strength to move forward himself.

The tale exists as a fiction within the movie. The vivid “Andersonian” images we see are an imaginary cinematic depiction of a stage play about Augie’s story, which unfolds as a “Twilight Zone”-esque teleplay hosted by Bryan Cranston doing his best Rod Sterling. Within this black-and-white TV show, Schwartzman plays an actor preparing to play Augie on stage, as if this Anderson regular, who once began his career as a fresh-faced, over-eager teen in “Rushmore,” has come full circle by playing a prototypically distant Anderson dad. Death, it seems, has forced him to mature.

Who is Augie Steenbeck, and does his story even matter when it comes wrapped in so many meta-textual layers of stories within stories? This has been a central question plaguing Anderson’s career at least as far back as “The Royal Tenenbaums.” That 2001 film, his third feature, displayed the first hints of the director’s “children’s storybook” aesthetic (which would later solidify in more child-centric movies like “Moonrise Kingdom”). Despite its candy-coated exterior, “Tenenbaums” dealt with mature themes like suicide and paternal aloofness, giving distinct rhyme and reason to the movie’s deadpan characters and tonal ennui.

Who is Augie Steenbeck, and does his story even matter when it comes wrapped in so many meta-textual layers of stories within stories?

“Asteroid City,” Anderson’s 11th movie, features many of these hallmarks while also continuing the more recent Anderson trend of using stories-within-stories. These have been a key part of his films for some time — the stage production in “Rushmore”, the in-world documentary in “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou” — but only with “The Grand Budapest Hotel” in 2014 did Anderson fully realize his vision of meta-fiction. “Grand Budapest” is essentially a story of escaping Nazi persecution, though it warps the details of World War II by presenting a pop-up book movie contained within an interview conducted decades later, itself turned into a novel being read by a little girl later still. The facts of the real Holocaust may be absent, but their emotional truth is delivered with a spoonful of sugar to assist with the bitterness — though the story being told is occasionally so bitter and horrific that even narrator Zero Mustafa (F. Murray Abraham) refuses to recall its most gruesome details.

Where “Grand Budapest” makes the case for Anderson’s style as a necessary filter for atrocities, “The French Dispatch” is a much more direct reckoning, especially in its sections influenced by France’s May ’68 revolution. Inspired by The New Yorker articles Anderson grew up reading, the film comes pre-wrapped in an editorial layer meant to tickle one’s intellect. He presents each story in the film as a piece of journalism being recalled at a later date, usually by its writer, about subjects like student protests, a painter on death row and the persecution of a James Baldwin-inspired author (who, like Anderson, searches for like-minded artistic influence in France, rather than the United States). He uses “The French Dispatch” to test his stylistic limits, crafting living dioramas and sending his camera spinning around dining tables as delectable dishes are served — it’s a dreamlike travelog — but after stretching his aesthetics to this degree, the rubber band snaps back into place in “Asteroid City,” which feels much more comfortable letting its performances and design elements speak for themselves.

All of these elements are drawn from different films throughout Anderson’s career. It features flimsy train cars whose physical un-reality is intentionally mismatched with a sense of emotional realism — Anderson’s trains may as well be metaphors for his own filmmaking — à la 2007’s “The Darjeeling Limited,” another Anderson story about grief. Nuclear horrors also unfold far in the background, as in his delightful (if culturally iffy) stop-motion movie “Isle of Dogs.” The latter may be set in a futuristic Japan — or a version of Japan that exists within the Western cinematic imagination (despite its authentic view of Japanese politics, courtesy story writer Nomura Kunichi) — but its backdrop occasionally echoes the real horrors wrought upon the Japanese by the United States, both in Japan and in the U.S., during World War II. The film follows sardonic, fast-talking canines whose forced internment bears at least passing resemblance to the widespread imprisonment of ethnically Japanese American citizens in the 1940s, while its mushroom cloud animations (and its setting, the fictitious city of “Megasaki”) are a much more overt reminder of the Atom bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Between “Grand Budapest,” “Isle of Dogs,” “The French Dispatch” and “Asteroid City,” Anderson’s work this past decade has not only sought to transform the stylistic hallmarks of his mid-20th century influences. It has also sought to ponder, through his aesthetic approach, the cultural and political influences on the very movies from which he borrows his images in the first place. The hallmarks of Japan’s post-war cinema have long been academic and casual favorites in the West, between Kurosawa, Ozu Yasujiro and the Godzilla movies, but that there was a need for such a cinematic reconstruction in the first place is a nagging realization that seems to echo somewhere in the subconscious of “Isle of Dogs” (and of “Asteroid City,” too). And so, he explores the meaning of his own images by approaching them more explicitly as fiction within his films, and thus more immediately ripe for viewing as creations of authors who often appear on screen. His visual signatures have always been recognizable, but rather than shy away from this fact, he leans into it, demanding greater scrutiny in the process.

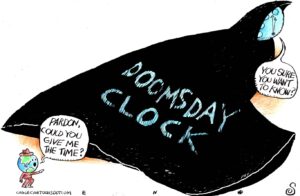

The fictitious town of Asteroid City is backdropped constantly by mushroom clouds. The Junior Stargazers may have their sights set on the moon, but Anderson is more interested in tapping into the anxieties of the early Cold War as reflected in the period’s science fiction (such as the Sterling-hosted “Twilight Zone”). In “Asteroid City,” questions about the nature of life and death abound — questions asked by children to the frustration of adults unable to answer them — culminating in the existential anxiety that accompanies the landing of a flying saucer, the design of which is taken straight off the cover of a ’50s sci-fi pulp novel.

However, the UFO isn’t merely a UFO. Unlike the sleek, silver saucers reminiscent of the era’s sci-fi, this one glows green. Like the trunk cargo in “Repo Man,” it evokes radioactivity and death by fallout. Once again, Anderson places real horrors — actual nuclear testing — far in the background, in favor of their storybook versions. The emotional fallout of this alien encounter is just as destabilizing as the existential threat of “the bomb.” Not only are children unable to fully comprehend mortality in “Asteroid City” their parents are woefully ill-equipped to deal with the questions themselves, especially once the aliens arrive.

Anderson further ties these anxieties to their contemporary equivalents — it’s his first movie written post-COVID-19 — by having his characters forced into “quarantine” after the alien encounter, as if the ship contained viral pathogens. As in the early days of the nuclear age, death has been in the air since the dawn of COVID, forcing children and adults alike to wrestle with mortality far more, and far earlier, than usual.

Once again, Anderson places real horrors — actual nuclear testing — far in the background, in favor of their storybook versions.

Plenty of Anderson’s films have been about grief, about father issues and about filial issues in general. But “Asteroid City” is the first to be told from a parental perspective. It is perhaps no coincidence that while Anderson’s early films had been inspired by his parents’ divorce — a recurring theme in the Spielberg sci-fi films that influenced “Asteroid City,” like “E.T.” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” — his films since becoming a father in 2016 have shifted their approach and understanding of parenthood. His stories of parents and children now encompass the idea of mortality both in the abstract — through ruminations on encroaching existential threats, and the weight of past horrors taught in history books — as well as directly and explicitly. Where his characters were once forced to face the deaths of parents, they now mourn romantic partners, which leaves them emotionally exposed not only to the possibility of lifelong isolation, as in Zero in “Grand Budapest Hotel,” but to immediate reflections of their own impermanence while having to ponder their children’s futures in their own absence, as Augie Steenbeck does.

Steenbeck shares a name with the analog editing machines responsible for so many films by Anderson and his cinematic forefathers. He is a version of the mature Anderson, the way Schwartzman’s high school character in “Rushmore” tapped into the director’s youthful naivete. He now exists in a world on the verge of collapse, where it is difficult if not impossible to hold on to childish things, and where death knocks constantly at his door. And yet, life perseveres. He continues to create worlds unique to himself, worlds that are familiar even as they evolve to accommodate new stages of life and the inevitability of death — the final page in even the most whimsical storybook.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.