From ‘Oppenheimer’ to ‘Repo Man’: Truthdig’s Guide to Nuclear Cinema

Surveying eight decades of onscreen atomic anxiety. Repo Man. (Universal Pictures)

Repo Man. (Universal Pictures)

With its $100 million budget, Christopher Nolan’s all-star biopic “Oppenheimer” is the most expensive movie about nuclear weapons ever made. But spending lots of money is no guarantee of a film’s worth or impact, especially in the extensive catalog of films about the bomb and its shadow. The 1984 BBC film “Threads” was made on a budget of $600,000 and remains the reigning king of nuclear-themed realism and despair. On Nov. 20, 1983, more than 100 million Americans watched “The Day After,” a made-for-TV movie by a middling director that left President Ronald Reagan so emotionally shaken, he devoted his second administration to reducing the threat posed by nuclear weapons, to the point of discussing their abolition with Mikhail Gorbachev.

Nolan’s movie is unlikely to join those films in the nuclear pantheon. It may not even be the best biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, contending as it does with the overlooked seven-part 1980 PBS miniseries of the same name starring Sam Waterston. But the limits of the nuclear film in 2023 says as much about the culture as the relative merits of Nolan’s filmmaking. The public just isn’t nearly as focused, obsessed or terrified of nuclear weapons as it was in the 1960s and the 1980s, the genre’s two golden ages.

But it should be. The Doomsday clock maintained by Bulletin of Atomic Scientists is currently set to 90 seconds to midnight. NATO and Russia are playing a game in Ukraine that has drawn informed comparisons to an extended Cuban Missile Crisis. Nuclear arms control has collapsed. New generations of nuclear weapons are being developed by the U.S., Russia and China. Wherever history ends up ranking the new “Oppenheimer,” it’s a very well-timed entry to a long movie tradition of reckoning with the bomb and its effects on human beings at every level, from the civilizational to the cellular.

With that in mind, here’s our guide to essential atomic movies.

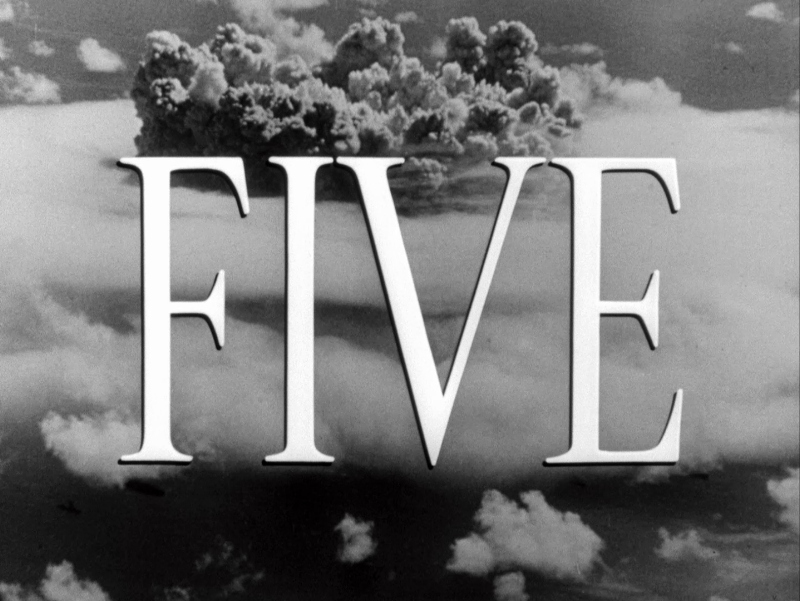

Five (1951)

The film that laid down the Geiger-counting gauntlet for dozens of post-nuclear survivor-group stories. Director Arch Oboler made his name as a playwright and proto-Rod Serling with the 1930s NBC radio program, “Lights Out,” before transitioning to Hollywood during the war. He begins “Five” with a trope that would become cliché, but was fresh at the time: a mushroom cloud, howling winds, screams and scenes of total destruction. No backstory to the catastrophe is given, because once it occurs, what does it matter? A group of four men and one woman straggle their way to the California coast, where they realize there is little to do but ponder their predicament and wait to die.

Gojira (aka Godzilla) 1954

When a heavily edited version was released in the U.S. in 1956, “Godzilla” was seen as just another monster picture. Ishiro Honda’s 1954 original, however, was a somber elegy and dark allegory aimed directly at Japanese audiences who had witnessed Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the ongoing H-Bomb tests in the Pacific.

The film’s opening sequence of a fishing trawler destroyed by a great flash of light was immediately recognized as a reference to the Lucky Dragon No. 5, a Japanese fishing boat whose crew was irradiated when they strayed too close to an aboveground test on Bikini Atoll. The coded message of Godzilla’s radioactive breath and rampage through Tokyo was likewise hard to miss. Did he represent the H-Bomb? The United States? The dangers of the Cold War and the unleashed, split atom generally? Japanese audiences had a pretty good idea, but you decide. Godzilla was killed off pretty decisively at film’s end, but the franchise he spawned remains with us, much like the nuclear arsenals that inspired him.

Day the World Ended (1956)

Roger Corman’s “Day the World Ended” opened shortly before the U.S. cut of “Godzilla”, but its own nuclear mutant proved forgettable. The fallout-created monster is a horned three-eyed creature that haunts a survivor camp, ravenous for irradiated flesh. According to Corman lore, production on the film wrapped on Nov. 22, 1955, just minutes before news broke of the Soviets’ first successful detonation of a hydrogen bomb.

On the Beach (1959)

Nevil Shute’s 1957 bestseller has been hailed as “Australia’s most important novel.” Stanley Kramer’s big-budget production of the same name hews close to the source material in its chronicle of a group of people on the Australian coast waiting for a radioactive cloud to encircle the Earth. Gregory Peck plays the commander of a U.S. sub that resurfaces after the war and docks in Melbourne. A pre-“Psycho” Anthony Perkins (who abandons his bad Aussie accent after two scenes) plays a low-ranking Australian Navy officer who’s ordered to join Peck’s recon mission. Viewed by the standards of later nuke war films, “On the Beach” seems hesitant and weak. But at the time, it represented a bold and sobering maturation of the young genre. “How do you tell the woman you love she has to kill herself and the baby?” asks Perkins. No answer is provided, because there isn’t one. Only the silence of an empty San Francisco harbor in the chilling final shot.

Panic in Year Zero! (1962)

Ray Milland plays a father on a family fishing trip in the Sierra Nevada when Los Angeles is destroyed by two hydrogen bombs. The depiction of social anarchy that follows — all switchblade hoodlums turned highwaymen — owes as much to the era’s juvenile delinquency obsession as it does to its peaking nuclear anxiety. Yet the film endures in the survivalist canon where it is revered as a formative influence. The lessons of the film have little to do with nuclear war being a horrible thing, and everything to do with the importance of leaving the city and stockpiling weapons, because after a nuclear war, the only survivors are cockroaches and assholes.

La Jetée (1962)

What Chris Marker accomplished with some styrofoam, some wires, a hammock, a sparse voiceover and a montage of black-and-white still photographs will always be a marvel. A story about love, the apocalypse and time travel, “La Jetée”’s bomb-shelter claustrophobia is as indelible as any subterranean postwar world created before or since. The images of Jean Négroni wincing in his underground medical chair, amid the incomprehensible whispers of his experimenters, not only elevated the nuclear war movie, it raised the conceptual bar on science fiction as a whole. All with a run time under 30 minutes.

Ladybug, Ladybug (1963)

One of the great, forgotten classics of nuclear cinema’s first golden age. Based on a McCall’s magazine story about true events during the Cuban Missile Crisis, “Ladybug, Ladybug” was the first film to focus on the psychological impacts of nuclear anxiety and war on children.

It’s heart-wrenching while staying true to the less-sympathetic, “Lord of the Flies” aspect about how young people might respond to, say, an overcrowded bomb shelter. The children begin to explore their feelings and form alliances during a long country walk to their homes. It ends with a boy and a girl denied spots in the town’s only well-stocked shelter. The girl hides in a lawn-strewn refrigerator. In the final frames, the boy frantically attempts to dig a hole under the screech of approaching bombers. When he realizes it’s too late, he turns skyward and screams, “Stop! Stop!” a full-throated wail that anticipates the knee-fallen Charlton Heston’s closing cry in “Planet of the Apes” five years later.

Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe (1964)

By 1964, everyone was in desperate need of a reason to laugh about the absurdity of the nuclear condition. Stanley Kubrick and Terry Southern answered the call with one of the funniest movies ever made and a perennial candidate for the best film of all time. “Strangelove”’s famous origins in Kubrick’s inability to play the subject straight has overshadowed the film’s serious twin, Sidney Lumet’s “Fail-Safe”, which appeared later the same year. In “Fail-Safe,” the failure to retract a bomber forces the coolheaded president (Henry Fonda) to “trade” New York City for Moscow in order to prevent a larger war. Walter Matthau’s portrayal of a hyperrational nuclear theorist can’t touch Sellers’ Strangelove, but is one of “Fail-Safe”’s minor pleasures.

The War Game (1966)

The granddaddy of both “Threads” and “The Office,” this seminal pseudo-documentary reflected the influence of a group of brilliant young documentarians that arrived at the BBC in the early and mid-60s. Among them was John Berger and Peter Watkins, who convinced the Corporation to sign off on what became a powerfully unnerving docudrama about a British city destroyed by thermonuclear weapons. The BBC board changed their mind when they saw the result, and with a little nudge from the British government, blocked the film, citing concern for “the effect such a shocking programme would have on the lonely, the aged and the depressed or disturbed.” Following a limited theatrical release, it won the Oscar for best documentary prize in 1967. The BBC finally aired “The War Game” in 1985.

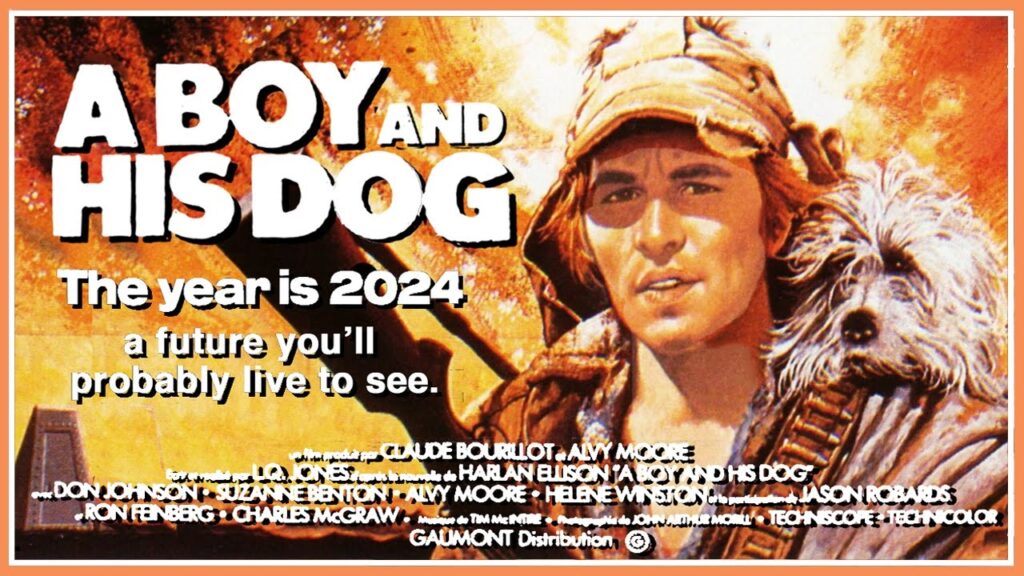

A Boy and His Dog (1975)

Adapted from a comic book by Harlan Ellison, this quintessentially ’70s sci-fi cult relic finds the teenage Vic (Don Jonson) scavenging the post-apocalyptic desert for food, water and the opposite sex. At his side is his trusty telepathic mutt, Blood, who speaks perfect English and is extremely good at sniffing out females for himself and his master. When Johnson is entrapped by an underground community and enslaved as a stud, he must escape and rejoin Blood to continue their adventures. If rumors of a remake are true, it will likely take the form of the never-realized sequel, “A Girl and Her Dog.”

Twilight’s Last Gleaming (1977)

Although he will always be overshadowed by Sterling Hayden’s Jack D. Ripper, Burt Lancaster was no slouch at embodying the humorless Cold War military madmen. He played a Curtis LeMay-type general in “Seven Days in May” (1964), and in “Twilight’s Last Gleaming” donned the uniform of a rogue Air Force general who breaks out of prison, commandeers an ICBM silo and threatens to launch nine Titan missiles unless he and his two fellow escapees get $10 million in cash and safe passage out of the country.

A classic ’70s Hollywood antihero, Lancaster evolves from being a villain to a sympathetic and even noble character. The Soviets are a running theme, as are the horrors of nuclear war, but it’s as much a post-Vietnam picture as a Cold War one. Lancaster’s character, we learn, was a respected general during the war who became an outspoken critic of U.S. policy after his return home. To shut him up, the Air Force arranges a trumped-up murder charge to send him away for life. Instead they created a would-be nuclear-armed precursor to John Rambo.

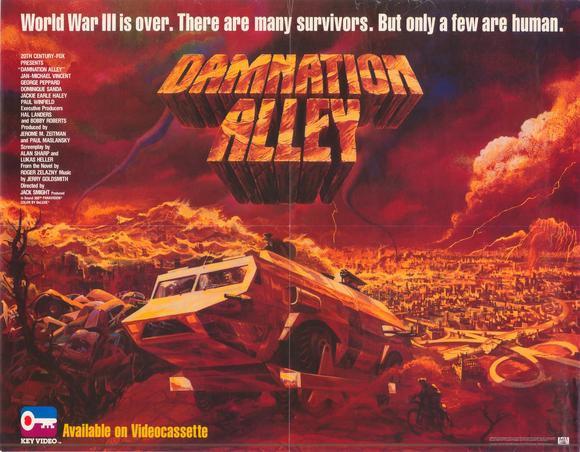

Damnation Alley (1977)

This mid-budget, post-apocalyptic, fantasy-adventure stars George Peppard as the leader of a ragtag wild bunch who roam a radioactive wasteland in a futuristic RV. In a role that presaged his “A-Team” turn, Peppard directs the group’s self-appointed mission to help more vulnerable survivors facing threats from marauding outlaws, giant scorpions and armor-plated, flesh-eating cockroaches. In a 10-minute prologue, we get some lighthearted banter during the change of crews inside a missile silo shortly before a Soviet first-strike. Distinguishing itself from what had become a tradition of showing nuclear blasts from ground level, “Damnation Alley” lingers on a wonderful shot from space as the surface of the earth glows with bright red flashes on every continent.

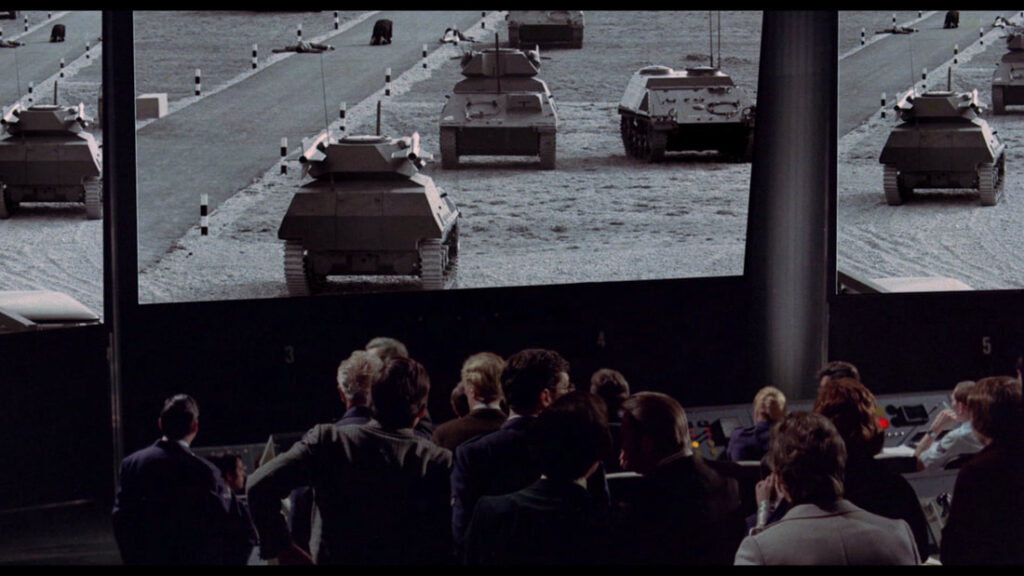

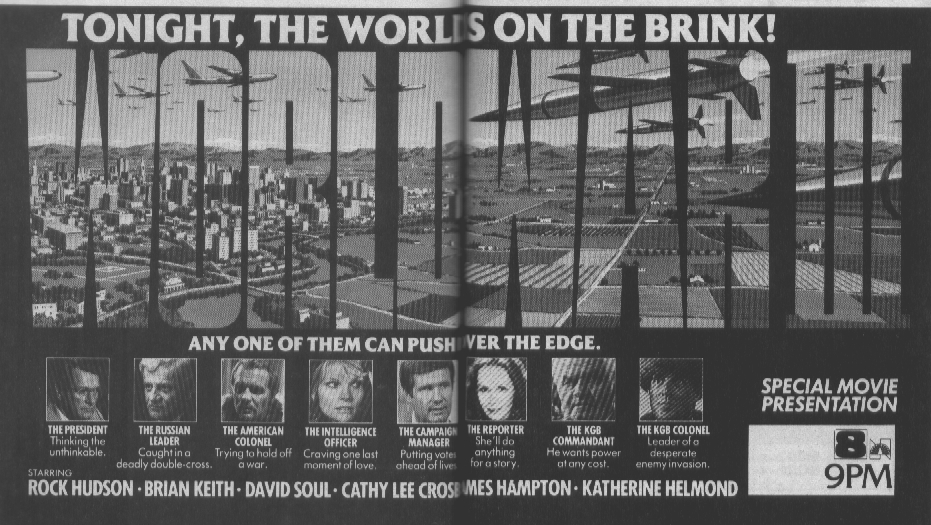

World War III (1982)

“World War III” ended the run of low-budget, sub- “Damnation Alley” wasteland fantasies that dominated nuclear films in the early-1980s. (The less said about “DefCon 4” and “Parasite,” in 3-D, the better.) This two-part, made-for-TV extravaganza features Rock Hudson as The President who orders a grain embargo against the Soviet Union, to which the Soviets respond by dropping a team of paratroopers into Alaska to sabotage the Alaskan oil pipeline. From here, things very slowly escalate until one of Hudson’s advisers recommends launching a tactical nuclear strike on Alaska. Although anticipating the schlocky conservative turn of “Red Dawn,” the film satisfyingly refuses to close with a traditional made-for-TV happy ending. Instead, it pulls the rug out in a final two minutes of mayhem.

The Atomic Café (1982)

Two decades after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the duck-and-cover generation was ready to revisit the Civil Defense films of their childhood nightmares. But this compilation of educational shorts, newsreels and fallout-shelter etiquette tips was always more than an exercise in gentle, knowing nostalgia. It arrived in the midst of the Freeze movement and dawning awareness that the first Reagan administration was out of its mind. Not only has nothing changed, but things were possibly even crazier 20 years later. In the words of T.K. Jones, Reagan’s deputy under secretary of defense for strategic and theater nuclear forces: “With enough shovels, everybody’s going to make it.”

Testament (1983)

A sleeper at the time that has since been overshadowed by “The Day After” and “Threads.” Haunting in its portrayal of daily life as fallout drifts into the lives of a bedroom community north of San Francisco, the film centers on the unraveling of a community that at first appears to survive the nuclear blasts, but then falls apart, bit by bit, as the invisible radioactivity does its incremental worst. The film features a young Kevin Costner and is based on a short story with mysterious origins.

The Day After (1983)

The Big One. Arriving at the screaming peak of nuclear anxiety generated by the Reagan administration’s “full court press” against the Soviets, “The Day After” was the culmination of nuclear cinema — a realistic depiction of the immediate blast and long-term fallout that left a nation even more shaken than it already was.

ABC set up emergency help lines for children and parents to deal with the terror the film inspired. Directed by Nicholas Meyer, fresh off of the set of “Star Trek II,” and starring Jason Robards, John Lithgow and Steve Guttenberg, the film depicted the impacts of nuclear war on the residents of Lawrence, Kansas, a perfect Spielbergian small town target that happened to be at the geographical center of the country, as well as surrounded by a half-dozen Strategic Air Command missile installations.

Unlike many previous nuclear films that followed a group of survivors, there was little unexpected heroism and personal sacrifice. Everyone just dies slowly, miserably of radiation poisoning. The film, which ended in a deliberate echo of Orson Welles’ 1938 “War of the Worlds” broadcast, famously unsettled the president of the United States. Following his viewing in the White House, he wrote a letter to Meyer expressing his feelings and began to think seriously about how the nuclear danger might be reduced, if not eliminated.

Threads (1984)

The slow grind realism of “The Day After” was soon superseded by “Threads,” a BBC production that aired the following autumn. Made on a shoestring budget of roughly $600,000, the film used a documentary style and a cast of mostly unknown actors to tell the story of a working-class Sheffield family surviving in the wreckage.

Unlike “The Day After,” “Threads” looked decades into the future, opening a grim glimpse into the long-term effects of nuclear war. Like “The Day After,” “Testament,” and “On the Beach,” it features a pregnancy subplot that provides the film’s gut-wrenching closing scene. As it approaches its 40th anniversary, it has lost none of its power.

Repo Man (1984)

While not explicitly about nuclear war, “Repo Man” is very much a product of, and a refreshingly weird and joyous rejoinder to, the nuclear anxiety of the early Reagan years. This anxiety is symbolized by the nuclear material in the trunk of the film’s elusive whale, a ’71 Chevy Impala. That “Repo Man” deserves inclusion in the pantheon of nuclear cinema is an opinion shared by none other than the nuclear physicist Sam Cohen, a colleague of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the father of the neutron bomb. After the film’s release, Cohen called director Alex Cox to express his admiration and invite him to lunch. At their meeting, the physicist gushed that his two favorite films were “Dr. Strangelove” and “Repo Man.”

When the Wind Blows (1986)

The animated film based on Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel tells the story of an elderly couple doing their level, Middle England best to follow the absurd tips offered by government survival manuals as they prepare for an imminent nuclear war. As instructed, they build a fallout shelter in their living room made from two doors. Directed by Jimmy T. Murakami, hand-drawn animation is interspersed with stop-action, beautifully rendering the aging couple’s naivete, sweetness and love for each other unto the last. The original soundtrack features songs by David Bowie, Phil Collins and Roger Waters.

Miracle Mile (1988)

Perhaps the strangest and most unexpected film of the lot appeared just as the Cold War was ending. Originally intended as the centerpiece of John Landis’ “Twilight Zone: The Movie,” (1983) writer Steve De Jarnatt refused to let Steven Spielberg change the ending and left to make the damn thing himself. Five years later, he released what seems for the first 30 minutes or so like a standard-issue ’80s romance, down to the Tangerine Dream score.

Instead, a budding relationship between jazz musician Anthony Edwards and diner waitress Mare Winningham is interrupted when Edwards receives a call informing him that Soviet missiles will be hitting Los Angeles in 70 minutes. The film then shifts gears into a darkly comic paranoid thriller reminiscent of Scorsese’s “After Hours,” with Edwards frantically searching for Winningham. All the while, the lingering question, as in “Ladybug, Ladybug,” is whether the alert is real, a test or a prank. The shocking ending breaks all of Hollywood’s rules in what turned out to be a satisfyingly surreal coda to the Cold War nuclear war movie.

Missile (1988)

Few of the films on this list are as quietly and coldly terrifying as Frederick Wiseman’s documentary, “Missile.” Best known for his 1967 documentary “Titicut Follies,” Wiseman somehow got the Air Force to greenlight his request to bring a film crew inside the 14-week training program for ICBM launch officers. There is no commentary, no editorializing, no outside talking heads, just verité footage of classrooms where teachers and students chat among themselves and discuss how to turn the keys on the deaths of billions of people. It could have been subtitled, On the Banality of Armageddon.

The Road (2009)

One of the debates surrounding Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 masterpiece of post-apocalyptic fiction concerned the precise nature of the unnamed disaster. But while he didn’t call it a nuclear war, he almost certainly meant to describe one. This is how he recounted the event in one of the novel’s flashback scenes: “The clocks stopped at 1:17. A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions. He got up and went to the window. What is it? she said. He didn’t answer. He went to the bathroom and threw the light switch but the power was already gone. A dull glow rose in the window glass.”

This is exactly how rural communities would experience the first wave of “countervalue targeting,” otherwise known as nuking cities. John Hillcoat’s film captures the novel as much as the studio would allow, but several key scenes from the novel were cut. And while Viggo Mortensen is perfectly cast, Kodi Smit-McPhee isn’t nearly skinny, pallid or sickly enough for the role of Boy.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.