We Are Those Who Suffer: Free Speech, the Media and the Roots of Violence

Condemnation of the Charlie Hebdo killings must be accompanied by understanding of root causes and by compassion for struggling peoples. And the media must refrain from fanning the flames of hatred. A banner hung in Paris after the Charlie Hebdo shootings last month reads, "Freedom, I draw your name." (Shutterstock)

A banner hung in Paris after the Charlie Hebdo shootings last month reads, "Freedom, I draw your name." (Shutterstock)

By Barbara SorosIf only we would think about what we are doing.

— Hannah Arendt

The brutal deaths at the Paris office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo have rightly drawn international solidarity for the victims and their families, as well as concern for the well-being of those who speak openly on political issues. It is impossible to mitigate the horror of this event, or condone it, but at the same time such a tragedy brings to the fore, once again, the deeper issues of free speech and the responsibility of the media, as well as an opportunity to reconsider some underlying causes of extremism.

Woven into the concept of free speech is that one can say whatever one wishes, no matter how outlandish, and if this is cloaked within a semblance of dignified language, or at least basic literacy or artistic representation, then anything goes. We have an intellectual and moral right to criticize, to ridicule, to poke fun at, to highlight what we imagine to be the essential nature of a problem. And this we should be able to do in spite of or within the apparent political climate.

There are no limits. Religious founders are lampooned by writers and satirists along with political leaders and movements, making correlations that may or may not exist between politics and spiritual beliefs. Of course, religion has always been manipulated by politicians and clergy to attain political and military objectives, serving as a vehicle for their ambitions. And because religion, and with it mythology, speaks to the more unconscious elements of humanity, to the invisible or mysterious forces of life, religious references are deeply felt and are woven into all questions of mortality, morality and human vulnerability and hence are useful in igniting fear and subjugating or manipulating social groups.

Let us think for a moment of the pseudo-Germanic mythology orchestrated by the Third Reich, how it rallied the German people to a common violent cause. Were the Teutonic myths in themselves responsible for the Nazis’ aggression? In Serbia both religious identity and a corrupted version of the defeat of Prince Lazar on the battlefield with the Turks 500 years earlier were twisted to gain compliance with nationalist territorial aims. In both cases foundations for fascist enterprises actually rested on ruined economies.

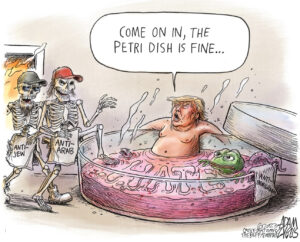

The media can be complicit in advancing prejudice and violent agendas. Before and during the Bosnian War, nationalist media spread stories to ignite hate and propel the aims of a Greater Serbia. In Rwanda, certain journalists played a crucial role in supporting widespread atrocities and, since, at least one has been indicted for alleged war crimes. During the Second World War, Jews were ridiculed by the German media, portrayed in grotesque caricatures, as were the Japanese by the United States and Americans by Japan. African-Americans have been, over centuries, demeaned in the supremacist press.

By comparison, Charlie Hebdo is an independent, secular, anarchistic voice and its offending covers and content may seem light and ribald and incapable of drawing such ire — until we recall the current climate. There are terrible tensions in the Islamic world. Tensions that historically began with colonialism and have been escalated by unchecked corporate and political interests, globalization on the march, have directly contributed to the rise of undemocratic governments in the Middle East and elsewhere, and have produced within Islamic groups extremists who, themselves, manipulate Islam to their goals and draw the disenfranchised into their service. But will satirizing Muhammad — or Islam, especially if there exist superficial perceptions of its underlying values and its current political implications — contribute to broader understanding of the fundamental global problems or elicit more extremism?

France has a robust history of potent political satire and polemics, both admirable and not. Molière, Voltaire, Montaigne, Tocqueville, Anatole France and Alfred Jarry are among myriad thinkers whose insights have nourished generations of French and non-French alike. However, remembering the depiction of racial prejudice with regard to the Dreyfus Affair, it is important to keep in mind that the act of lampooning may be interpreted by its targets as a pointedly aggressive act. We are clever because we are capable of satire and irony, but these can humiliate, serving as a brutal knife, and when symbolically portrayed can cut deeply, penetrating the unconscious and thus may elicit irrational responses. In effect, we counter violent acts with intellectual violence. We strike back and hence may wittingly or unwittingly contribute to the mayhem.

At the root of global suffering and acts of terror resides a pervasive class divide, an elitism, and with this all the injustices of exceptionalism. How many years can people endure being marginalized, disenfranchised, excluded, suspended between social spheres within their own country — whether it be at peace, as in France, or within a conflict zone, as in Iraq, where regional and international interests have annihilated populations, pillaged resources, manipulated internal politics, created and funded militant groups, destroyed infrastructures, poisoned environments, reduced economies to ruins, and shown blatant disregard for existing cultures and been busily at work dismantling these? After all, with no intact or stabilized reference points to the past, how can a culture journey forward?

What would we do were we subjected to extremes of poverty, hopelessness, political humiliation, marginalization and futility, as the people of more and more societies are? I imagine we all would rise up to protest and, if our expectations were repeatedly frustrated, we might try to strike back, as some Muslims have.

Until we, all human beings, attend to the very real problems of existence in a universally affirming way, allowing each person a dignified life; until we each admit our role in benefiting from the status quo at the expense of the suffering of others and the destabilization of the planet; until we are able to embrace our own responsibility, then we too, each one of us, remain culpable of ethical malfeasance. Until we admit that we are all, in fact, complicit, through our silences and thoughtlessness, in a universal aggression upon and exploitation of cultures and the earth, I doubt much progress will be made. Tragically, further violence may ensue and many more across the globe, as is happening now in Nigeria, will be touched by physical aggression, war, environmental catastrophes and the spread of poverty and mass migration.

Can such a future be prevented? Marshall Rosenberg, psychologist and founder of The Center for Nonviolent Communication, has given us a clue when he said, “Violence is the tragic expression of unmet needs.”

The media have amassed enormous influence. But with this influence comes a responsibility that can be neglected: the responsibility to future generations, and with it the need to reflect deeply on the pulse of the times and consider the effects of information released to the public. Will it illumine the situation at hand, or will it simply just add to the confusion, the chaos, the violence, and the spectacle of politics that often replaces actual social insight? This is difficult and complex to prejudge, requiring a certain sagacity, but it is something to continuously revisit.

The people of Paris have been shocked but are on their feet. Metros have been stalled in tunnels, buses rerouted, police killed. There have been shootouts and deaths of hostages and suspected assailants. Though calmer for the moment, the city remains on red alert, as is the rest of France.

Both French and European Muslims and Jews are vulnerable. Xenophobia, already prevalent through Europe, has strengthened. This has resulted in rising numbers, 15,000 expected this year, of French Jews leaving their home country, seeking safety elsewhere, thus joining an exodus started four years earlier. Since the murders, there have been attacks on mosques, threats to French and Belgian synagogues, the vandalism of a Jewish graveyard in Eastern France, and the recent shootings in Denmark. Anti-Muslim rallies have been held in Germany, though with a greater assembly of those supportive of Islamic German citizens. In England, Muslim schoolchildren are exposed to bullying and ridicule. Troops have been sent to protect religious and community sites in various parts of Europe.

France has launched a campaign against anti-Semitic expression or the condoning of terrorism and has made arrests, including of Muslim dissidents who oppose Zionism. A French aircraft carrier has been deployed to the Middle East, the French Parliament has voted to extend the bombing campaign against ISIS, and extremists are being routed out through Europe. Though France’s, and on a broader scale, Europe’s, needs to take precautions and make a strong reprisal are understandable, it might be asked if these steps will be fruitful in creating a more secure world and promoting understanding.

Nearly 4 million people assembled, on Jan. 11, in a stunning show of solidarity, throughout France, with almost 2 million of them in Paris. As if to mock the serious concerns of French citizens and their stand against aggression, European and other global leaders who led the silent vigil in Paris included among them some engaged in squelching freedom of expression through the persecution or silencing of journalists and dissidents and in serving violent agendas.

There is so much more to the story, as there always is — a great deal more than extremists attacking a progressive but perhaps belligerent news publication, formerly obscure to the rest of the world and catapulted into fame by terrible events and media support. Soon after the attack, 7 million copies of a new edition of Charlie Hebdo were released (followed by more recent editions) in four languages, with covers and interior ready to offend or unite, depending on the audience. In response, churches have been burned and people injured or killed in Niger, and a massive rally in Chechnya and irate demonstrators in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Gaza have demanded deference to their religion (one major foundation of their cultures and of their capacity to endure), as well as apologies from France and the breaking of diplomatic ties.

Shall we ask them, as we must ask ourselves, if Charlie Hebdo is heroic or just provocative, and are our needs for unimpeded expression greater than the need for respect on the part of those who were offended? And can we understand that those who protest may not agree, not hold in the highest regard one country’s — in this case France’s — attachment to a particular interpretation of principles of freedom of speech exercised at their expense, when they have struggled and do struggle for the right to exist? Are they not asking to be included in the conversation?

There are other heroes, those who must endure a similar struggle firsthand in repressive societies around the world. Do we have the courage, the same daring strength as the French, to stand with and for them? From a humanist perspective, nous sommes ceux qui souffrent — we are those who suffer. It is the hope of many that new methods of diplomacy and compassionate dialogue followed by just action and compromise will be utilized to resolve differences and inequalities, as violence is never an answer. The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, both located in Geneva, are successful examples of the international application of more creative methods of resolving or preventing armed conflicts — the former organization as an independent diplomacy group and the latter as a model for securing pivotal roles for women in promoting peace. Martin Luther King Jr. believed “that unvarnished truth and unconditional love will have the last word in reality.”

Perhaps one optimistic moment came in late January at the European Union meeting in Brussels for the prevention of terror. That summit emphasized cooperating with Arab countries rather than placing blame, as well as addressing the conflicts in Syria and Iraq and, in the long term, considering the root causes of extremism. This would be a monumental task and would require much soul-searching and the sincere adjustment of priorities. But the question remains: Are these goals reachable within the existing and pervasive framework of profound political and economic disparities?

The targeted killings in Paris have brought to the world’s attention the injustices fermenting within French society. The social battlefield that is France, and by extension Europe, is now in clear view, and with it, once again, the greater battlefield that is the world.

Though at first it may not seem so on the surface, this is about more than freedom of speech. We are being asked to review the existing global conditions of liberty, equality and fraternity—values in which France has historically led the way. Let us hope that it will lead once again, courageously revisiting its social policies, and that in turn media organizations will pledge their service to a universal, egalitarian mission.

Editor’s note: This article will appear in the March/April online edition of Resurgence & Ecologist.

Barbara Soros has worked in the fields of human rights, reconstruction after war and traumatic recovery. She has written for children and for theater and is working on a book of intimate reflections on postwar life.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.