Wall Street Revisited: Greed Is Good and Dull

The inherent problem with Oliver Stone's follow-up to his 1987 classic is that it does not have the courage of its own nastiest convictions.

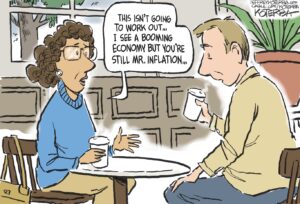

The best moment in “Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps” occurs in its opening sequence. The notorious Gordon Gekko is retrieving his personal property as he checks out of the slammer after much too long a stay. Among the items handed over to the onetime Wolf of Wall Street is a cell phone that is roughly the size and shape of an orthopedic shoe. The times, we quickly, humorously perceive, have been a-changing. Gekko is soon flogging a memoir the title of which turns his most famous saying into an interrogative: “Is Greed Good?” Yes, he answers, “it’s even legal.” Which turns out to be what this astonishingly inert sequel has as a moral.

There is no longer room for free-spirited buccaneers in the world’s money markets. Their appalling and amusing ways have been co-opted, institutionalized and dulled down by the banks, brokerages and insurance companies that we all know were responsible for our current Great Recession. In its vague way, Oliver Stone’s film, written by Allan Loeb and Stephen Schiff, aspires to explain how that came to pass, but quickly throws up its hands. There are, someone says, only about 25 people in the world who fully understand things like credit default swaps — none of whom has come within hailing distance of this film, the chief business of which is to enlist our sympathy for Gekko.

This is not as hard to do as Stone and company think it is. Michael Douglas’ Gekko was always a charming and ironic rogue, who had a way of speaking cheeky truth to power while more or less cheerfully lining his own pockets. He dubiously insists that back in the day his crimes were victimless. Now, however, entire nations can be brought near to ruin by the free range of much vaster speculation (and peculation) not so much managed as ridden by people as faceless as they are feckless.

That leaves Gekko — his family ruined, a son and a wife lost, his only daughter deeply estranged while he is himself pretty much down to his last, slightly encumbered $100 million — as the movie’s sole point of interest. He wants to make up with his daughter (Carey Mulligan), an idealistic Internet entrepreneur, who is engaged to Jake (Shia LaBeouf), a Wall Street trader heavily (and also idealistically) invested in an alternative energy start-up. Along the way, young Jake wishes to gain revenge on a powerful, charmless Wall Streeter (Josh Brolin) who ruined Jake’s kindly old mentor (Frank Langella).

As you can see, there’s a ton of plot in this picture — the family aspects of which we have experienced in many previous movies and TV shows, the financial aspects of which are murky and unfocused. Feel free to consult your mental cheat sheets in order to stay a couple of jumps ahead of Gekko and his get. Feel equally free to try to “follow the money” as Deep Throat so wisely advised us a few centuries ago. But mostly what we do is follow expensively tailored men into boardrooms where they threaten to crush one another with incomprehensible financial blather, angry outbursts and nasty sneers. As an alternative, they are often discovered wandering through Manhattan’s streets and parks (or riding its subways) — it’s called “opening up” the picture — murmuring threats and speaking of schemes so veiled they sound like invitations to the office Christmas party.

The inherent problem with this film is that it does not have the courage of its own nastiest convictions. In some part of their souls — or in the souls of the actors playing them — leading characters like Gordon Gekko want to be liked. No actor this side of Klaus Kinsky really wants to be fully loathed, and we in the audience are complicit in this desire. We want to confine flat-out villainy to the edges of the picture, where the character actors live their colorful half-lives. But if we cannot understand what is moving these people, if their plots and counterplots are not clear to us, the film dwindles in our eyes. This was a problem in the first “Wall Street” and it reaches crisis proportion here. The more a rather weary Gordon Gekko comes to resemble his namesake, that cute, earnest little lizard in the Geico commercials, the less entertaining he is. He occasionally smirks knowingly, but really he’s just another sad dad suing everyone for favor.

The film speaks from time to time about “moral hazard,” a concept people keep fruitlessly trying to explain to me. But what about “amoral hazard” — the idea that the big money has became so nimble, and faceless, that it is beyond anyone’s ability to understand, regulate or convincingly dramatize? I guess that, by default — that impotence — is finally, subtextually, what this film is about. But if some financial institutions are too big to fail, the current state of the financial world is too vaguely defined to succeed narratively. As this movie’s subtitle would have it, “money never sleeps.” But movie audiences are frequently on the cusp of that state. And this is a movie that perversely grants them their need — a few blissful moments in the Land of Nod.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.