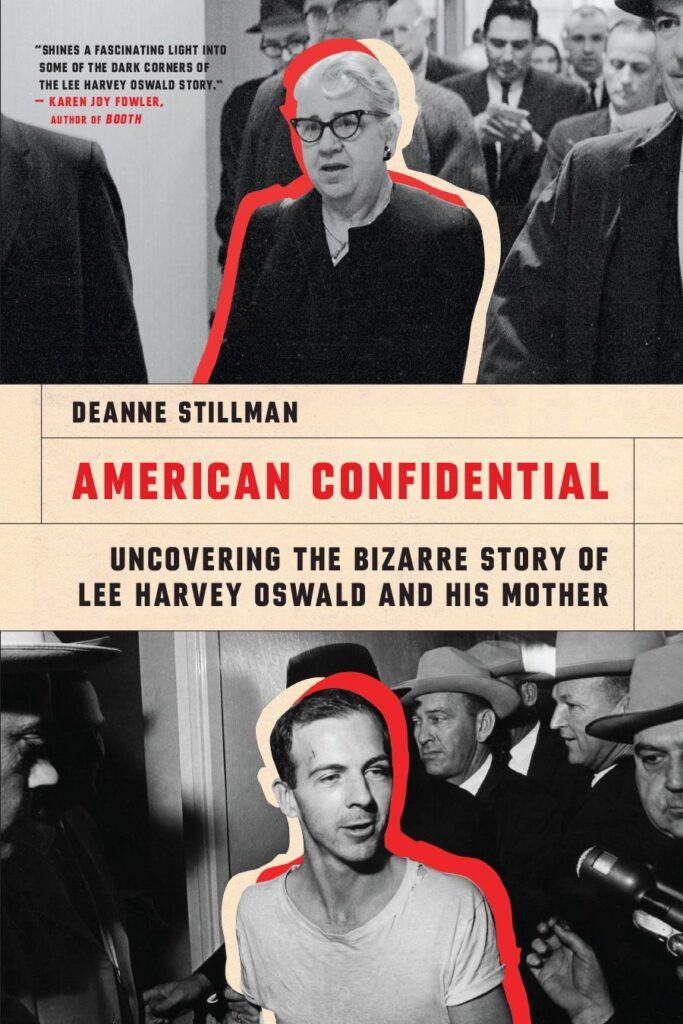

Uncovering the Bizarre Story of Lee Harvey Oswald and His Mother

What Lee Harvey Oswald tapped into and made his own has taken the country into years of violence. Lee Harvey Oswald, center, is shown in custody at a Dallas police station, Nov. 23, 1963. (AP Photo)

Lee Harvey Oswald, center, is shown in custody at a Dallas police station, Nov. 23, 1963. (AP Photo)

From American Confidential: Uncovering the Bizarre Story of Lee Harvey Oswald and his Mother. Used with permission of the publisher, Melville House Publishing. Copyright © 2023 by Deanne Stillman.

INTRODUCTION: CONSPIRACY OF ONE

“The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer.” — D. H. Lawrence

“But officer. How come the other guy didn’t get a ticket?” – oft-asked question in America, with many variations

“My son is innocent.” – Marguerite Oswald

With every one of my books, there always comes a moment when the subject matter is completely overwhelming and sometimes unbearably sad. I have to step away, sometimes for months, and then something inevitably pulls me back in. Actually, it’s more than that; some sort of miracle unfolds, and I take such occurrences as a sign to stay the course, and not to ignore my original instinct. So, just when I was feeling utterly morose and bereft while working on this book, there did come one of those universal indicators. My computer had crashed weeks earlier and I had to switch servers for whatever reason, and therefore a number of links had vanished.

I love looking into the backstories of my characters, especially because I always find things that others have overlooked, and with these two, Marguerite and Lee Harvey Oswald, I had discovered many things that were crucial to my story and to puzzling them out regarding temperament and how they moved through their worlds and the world at large. To a great degree, I had already laid a serious foundation for this book. With the vanishing of my server, it was all gone, and that only added to my discouragement. While I had remembered what some of the links were, there were literally dozens. The disappearance had been a total nightmare.

Then one day, my original server opened of its own accord—really! I hadn’t even clicked on it, and there they were: what seemed like miles of links, and I could immediately retrieve what I needed. These included a trove of links having to do with Lee and his mother, pathways I had been saving for months. On the day they reappeared, it was as if my road map, or at least a “this way” arrow, was once again directing my journey. When the links manifested themselves, I realized I just hadn’t been ready to continue this journey until that moment, no matter how much I had thought about it over the years. So just when I needed it most, there was the skeleton key (and, in the end, in the sense that Lee Harvey Oswald haunts this country, he is very much a ghost), a miraculous visitation from the digital ethers.

As I began scrolling through the links, one jumped out. This was the link to an exhibit at the Bronx Zoo that debuted on April 26, 1963, seven months before John Fitzgerald Kennedy was assassinated. The exhibit was called the “Most Dangerous Animal in the World.” It was a mirror. In other words, you would look into it and see yourself. The installation recalled the matter at hand, and not just in a general sense. Lee Harvey Oswald lived and played in the Bronx when he was a teen-ager, during 1952 and 1953, often hanging out at the zoo after he and his mother moved to an apartment that was within striking distance of it, seeking communion with the wild animals behind bars and in cages. It was at the Bronx Zoo that he was busted for truancy—the truant officer, it’s been said, laughed at his hayseed getup, his jeans, and his corresponding Texas accent (though it’s not really discernible as such on subsequent recordings)—and thus, as we shall see, a marker in his life was reached.

There followed hearings and juvenile lockup and probation and warnings, and shortly after his troubles in the Bronx his mother ignored a note from his probation officer asking for another meeting, and the pair moved back to New Orleans, hometown to both mother and son. That time in the Bronx was a crossroad—or one of them—that sent Lee en route to Dallas ten years later—the moment that changed history and allowed him to enter into it.

Lee liked animals, his mother later told everyone (but so what? a lot of killers like animals; John Wilkes Booth loved flowers and butterflies and once said that fireflies were “the bearers of sacred torches,” and then he shot Abraham Lincoln in the head). Yet clearly, for Oswald, there was something going on at the zoo that was a draw. I’ve long wondered which animal Lee most identified with. Was it the great apes? Not likely. Reptiles? Probably not. He did have dogs as a young boy and once even gave a puppy to a neighbor, probably as a way of seeking something else (friendship, refuge, gratitude?). He also gave his mother a bird in a cage years later. But then again, he used to shoot squirrels—a not-uncommon thing in rural areas across America and in Texas, where he once lived with his brothers. Yet one of them, his older brother Robert Oswald, remarked after the assassination of JFK that Lee’s killing of rabbits, one in particular, when they were hunting, was of a nature that was cruel and unnecessary. So was it lions and tigers at the zoo that he went to visit? I would venture a yes. They are powerful and majestic predators who would catch the fancy of any teenage boy.

We can imagine teenage Lee gazing at one and trying to make eye contact, perhaps doing so, and returning to visit that one, engaging in a conversation with it (as many of us would in those situations). “I know . . . you want out,” he might have said out loud or thought to himself. “Who doesn’t?” Maybe he even apologized for the lockup, and then when the truant officer busted him, asking why he wasn’t in school, maybe he shrugged and said, “See ya later, alligator” to his animal friend, a typical teenage wise guy. And it could have been later that day or around that time that he pulled a small knife on his brother’s wife or shot a BB gun at elderly folks in his building—the BB gun a perennial gift from parents to sons—and, as always, his mother made excuses.

We had all become eyewitnesses to the crime of the century.

Later, back in his hometown of New Orleans, Lee frequented Audubon Gardens, known for its walkways of live oaks and its famous Tree of Life, an enormous oak with boughs that reach the ground, and then, much later, when he returned from Russia with his wife Marina, he would take her there for visits. It’s not something we picture the assassin doing, for such information has been glossed over or not even ascertained, and it took me a while to imagine Lee taking a woman he loved (or had some sort of relationship with, clearly a complicated one) to what is traditionally a romantic location. Did he see his reflection in the lagoon, a foretelling of the Bronx Zoo installation? Did he linger under the Tree of Life or venture next door to the adjacent zoo, expressing excitement about the prospect of visiting the animals? It was literally a walk on the wild side, the name of Nelson Algren’s famous dark novel set in New Orleans which featured the legendary drifter Dove Linkhorn and other outcasts of the Big Easy. Later, Hunter S. Thompson would say that the Hell’s Angels were manifestations of these characters, the offspring of Linkhorn and his associates on the streets. Was Lee Harvey Oswald a rebel without a cause? While he certainly allied himself with various causes, and he may have convinced himself that one or the other of these was an identity for him at one time or another, the only cause he really had was himself—a distinctly American condition that in his case, and in the case of many who have followed the killing path, could have revealed itself in only one way.

Like many of my generation, I first learned of the assassination in junior high school. I was sitting in my eighth-grade classroom, and there sounded the melodic notes of a xylophone on the public-address system, signaling an important announcement. “Boys and girls,” said the principal. “This is Mrs. Lang.” Her voice quavered and she cleared her throat and went on. “I have some terrible news. The President has been shot.” She could barely continue, and there were gasps across the room. “At 12:30 today, he died.” We could hear her crying then, and she said some other things that I don’t remember and then the signing-off tone was sounded and there was sheer silence. There followed expressions of disbelief and gasps; there was weeping and the shuffling of papers. A body blow had struck our schoolroom just as surely as if we were in Dallas at the moment JFK was taken down while riding through Dealey Plaza in his motorcade. Very soon after the announcement, class was dismissed and we all returned to our homes, joining citizens across the land as we all turned on the television set and watched. There it was, over and over again, the news reports and the limo with the President careening away from the site of the assassination and sobbing reporters and onlookers everywhere, each person, one and all, struck by the shot heard round the world. We had all become eyewitnesses to the crime of the century, compounded by the fact that we soon watched another murder: two days after Lee Harvey Oswald had killed the President, he himself was killed before our eyes in an act that heightened the nightmare. We were to spend the rest of our lives trying to understand what happened.

At the time of the JFK assassination, my parents had recently gotten a divorce. It was an unexpected act that ruptured my family, shattering our snow globe in a way that still reverberates decades later. Fortunately for me, my father had taught me how to write, and I don’t just mean write down the alphabet and compose sentences, but write stories and plays and scenes and all sorts of literary concoctions.

Together we would invent characters and watch the news and wonder why and how things led to other things, and we would marvel at all the strange things people did. “You can’t make this stuff up,” my father always said, and over the years I have come to realize that you certainly can’t. When my mother and sister and I ended up on the “wrong” side of town following the dissolution of my parents’ marriage, I picked up pen and pad, and I haven’t stopped writing. It was a way out of turmoil and into a universe of endless possibility and attempts to heal the world. Looking back at things that I wrote then, I see that my concerns had to do with a wish for people to stop fighting, written as only a little girl can. I discovered pieces such as “They Got Divorced at the End of a Decade” and something called “Security Council,” a story about how the UN kept us all together in spite of wars that were raging everywhere. I’ve come to realize that the pieces I wrote long ago prepared the way for all of my books; they were expressions of a desire for reconciliation, mostly about internal family rifts and a disconnect from surroundings. My subsequent explorations of our shadowlands have taken me right into the dark heart of the American dream. Perhaps it was inevitable that I now turn to the act from which the country has yet to recover.

We are in an era of great flux, involving mass extinction of wildlife and severe weather changes, and when it comes to atmospheric upheaval, the situation on the ground in the United States is moving on a parallel track, rife with all manner of violence, often involving guns. Discussion of men who commit violent acts is front and center, with terms such as “toxic masculinity” and “dysfunctional families” swirling through the ethers. There are countless social media forums dedicated to ongoing gun violence in America, and those who commit violent acts often record them via “selfies,” knowing that records of their acts will fly from forum to forum and in those quarters they will gain attention by becoming idolized or scorned. The country is so obsessed with true crime and how and why the crimes have happened that it can’t stop listening to podcasts about said criminal acts, featuring blood-soaked recreations and graphic interviews with those involved, including cops, victims, and perpetrators.

With the sixtieth anniversary of the assassination of JFK upon us, it’s time to revisit the man in whom such afflictions took root and exploded onto the national scene, before these afflictions had names that were part of daily vernacular. And it is also the time to cast a new light on his mother, the progenitor, after all (his father died before he was born), and learn what we can about her hopes and desires, her involvement with the promise and failure of the American dream, how she passed on such information to her benighted son—and, ultimately, how he chose to respond to this knowledge.

There are dangerous animals everywhere, and the shots fired that day in Dallas are ricocheting in the malls and schools of today.

In 1965, the writer John Clellon Holmes penned a piece for Playboy called “The Silence of Oswald.” Many of our citizens, he wrote, possess “cocked rifles [and are] walking anonymously through the streets, with little or nothing in our society, offering any sure way by which these rifles can be disarmed. At least not until they have gone off, and it is too late.” While the conventional wisdom suggests that making access to certain guns more difficult will solve this problem (and indeed, it is a necessary Band-Aid), what goes on in America does not go on anywhere else in the world, and easy access to guns alone does not take us to the heart of the problem. As we shall see in American Confidential, the credo of the Wild West—“It’s a free country and I can do what I want”—takes us right to the center of our love affair with violent self-expression. When coupled with a disconnect that runs through many families, with personal pathologies shaped by those families, there is nothing that can stop this violence—other than meeting the shadow that haunts America and many of our young men.

“It is believed that more words have been written about the assassination [of John Fitzgerald Kennedy] than any other single, one day event in world history,” Vincent Bugliosi wrote in Reclaiming History, his sweeping study of that subject. This includes over one thousand books and countless articles, essays, and songs. Most of the books (with several exceptions that explore Oswald family dynamics) present conspiracy theories, and I’ve read a number of them. “Things have been reduced to this mind-numbing debate about forensics and ballistics that really misses the whole point,” the great novelist Robert Stone has written. In fact, his own book, A Hall of Mirrors, written three years after the assassination, sounds the depths of that moment and portrays an Oswald-like character who is a creature of the corrosive atmosphere of New Orleans, Lee’s birthplace.

To broaden the conversation about this thing that plagues us, in this book, I reverse the conventional narrative about Lee Harvey Oswald and suggest that it’s of little consequence if he was a patsy, a spy, a double agent, or any of the myriad other roles he is said to have played in the assassination of America’s thirty-fifth President. I suggest that whether or not he had accomplices or was used, whether or not he acted alone, as a solitary figure, a nobody, the act of destroying America’s most powerful and adored figure, a somebody, was his only route to immortality, the only way for a man with his temperament and legacy to pass a different one on. As we shall see, Oswald’s act was class warfare writ large—America’s dirty little secret front and center, in full bloody dimension on our television screens, if only it had been recognized as such at the time. In the end, for all the questioning and riddling over his motives in the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Lee Harvey Oswald was simply fulfilling his mother’s lifelong dream—to matter. In the end, they were a conspiracy of one.

On November 22, 1963, JFK was shot in the head, but America was shot in the heart. To this day we have yet to recover. The young boy who liked to gaze at stars and aim his toy guns at strangers became the living embodiment of the installation at the Bronx Zoo, the “Most Dangerous Animal in the World.” By enacting the wildest thing possible for a man of his making, taking down the President of the United States, he had broken out of his cage at the age of twenty-four and entered the stream of history. “That fellow Oswald uncorked something in this country,” JFK’s brother Robert said following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968—and then he himself was assassinated shortly thereafter. His remark couldn’t have been more accurate. What Lee Harvey Oswald tapped into and made his own has taken the country into years of violence. There are dangerous animals everywhere, and the shots fired that day in Dallas are ricocheting in the malls and schools of today. “You talkin to me?” Oswald seems to be saying in the famous photo of him with his rifle, years ahead of Robert DeNiro as Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver” standing before a mirror and trying out poses with a gun. “You talkin to ME?” “Who’re you talkin to—me?”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.