The Women Who Are Staring Down Duterte

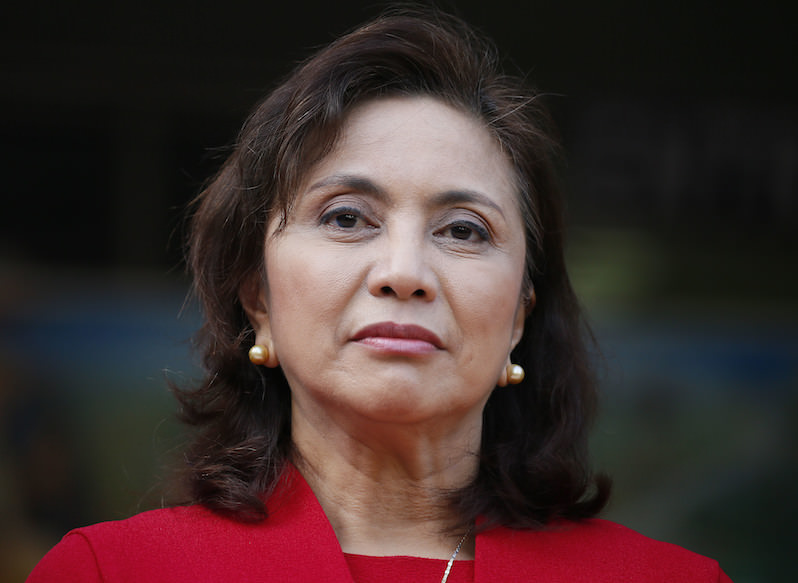

In addition to his ruthless anti-drug policies, the Philippines president is known for undermining women, but they continue to defy him. (Pictured, Vice President Leni Robredo, a Duterte critic.) Philippines Vice President Leni Robredo has drawn the ire of President Rodrigo Duterte for calling attention to the extrajudicial killings occurring since he took office. (Bullit Marquez / AP)

Philippines Vice President Leni Robredo has drawn the ire of President Rodrigo Duterte for calling attention to the extrajudicial killings occurring since he took office. (Bullit Marquez / AP)

Philippines Vice President Leni Robredo has drawn the ire of President Rodrigo Duterte for calling attention to the extrajudicial killings occurring since he took office. (Bullit Marquez / AP)

Editor’s note: This two-part series probes the political situation in the Philippines, where state authorities are allegedly orchestrating a wave of extrajudicial killings, mostly of drug users in the poorest neighborhoods of the country. The fiercest resistance to these state-sponsored crimes has come from two female legislators, as well as women’s rights activists and the young women who have stood in solidarity with them. Read Part 1 here.

After Sen. Leila de Lima, Vice President Leni Robredo has been President Rodrigo Duterte’s strongest critic in the Philippine government. She is also de Lima’s staunch political supporter and international defender.

“Efforts to smear Senator de Lima are a strong indication that the charges against her arise from a political agenda,” Robredo has claimed. “These efforts began soon after she launched an investigation into the issue of extrajudicial killings under the present administration.” De Lima is imprisoned on drug trafficking charges that the senator says are false and intended to silence her criticism of Duterte.

Robredo also questioned why no action has been taken on the 500 complaints against Duterte lodged with the Philippines Commission on Human Rights. After visiting de Lima in prison, the vice president pointed out that the country has an unfortunate history of trying to silence and destroy its critics through political harassment and manipulation of judicial measures.

When both the president and vice president made official appearances at an event commemorating the victims of Typhoon Yolanda, one of the most devastating natural disasters in the Philippines, Duterte joked about Robredo’s beauty and commented on her skirt and knees. “Ma’am Leni wore a dress that was shorter than usual. The protocol officers probably noticed I was always behind her. I told [Finance Secretary] Sonny Dominguez, ‘You’re too far, come closer. Check out her knees. …’ ”

When pressed by the media as to whether the remarks were insulting to women, Duterte argued that he was trying to lighten up a solemn event. In a more defensive retort, he said, “Do not exact a standard for me! I will do what I say, and I will say what I do.” Robredo tried to ignore his comments, but later, at an International Women’s Day event, she said, “We [women] are expected to stay silent when someone makes our knees and legs the subject of discussion.” She also recalled how during her political campaign, she received messages telling her to stay at home, that she is “just a widow and is incapable of the job.”

Duterte’s party members have called for Robredo’s impeachment. Not only did they seek her ouster, they also have selected her replacement—Sen. Bongbong Marcos, who lost by a small margin to Robredo in the vice presidential election almost a year ago. Bongbong—a nickname in a country where, to outsiders, the choice of diminutives may seem strange and unflattering—is the son of the late Ferdinand Marcos, former dictator of the Philippines.

In the 1980s, the Marcos regime instituted martial law and imprisoned, raped and tortured his opponents, while orchestrating the deaths of thousands of Filipinos. Transparency International named him the second most corrupt leader of all time after investigating his theft of $10 billion from state funds. I know well this shameful period in the country’s history, because a number of those who suffered in detention were and are my friends.

For many years, the Marcos family sought to bury the ex-president’s body in the Philippines’ “heroes’ cemetery.” When President Fidel Ramos allowed Marcos’ body to return to the Philippines in 1993, the family kept it in a glass casket at his former home in the northern part of the country. Every subsequent president has refused the family’s request for a hero’s burial because of the dictator’s crimes. This year, Duterte, a longtime ally of the family, decreed that Marcos deserved to be interred in the heroes’ cemetery because he had been a president and veteran of World War II. The Supreme Court then approved the burial, dismissing the petitions of martial law victims who tried to stop it.

Robredo has been forthright in her opposition to sanitizing Marcos’ name and to the garlanding of a death dealer. “How can we allow a hero’s burial for a man who has plundered our country and was responsible for the death and disappearance of many Filipinos?” she asked. “He is no hero.” She strongly condemned the burial, saying, “Like a thief in the night, the Marcos family deliberately hid the information of burying former president Marcos today from the Filipino people.”

Duterte has played a schizophrenic cat-and-mouse game with Robredo. Prior to his inauguration, Duterte did not offer her a Cabinet role, which is customarily given to vice presidents, even those of the opposing party. Later, he informally offered her the position of housing secretary during an interview with a journalist who pressed him on whether Robredo would be given a Cabinet spot. Duterte taunted, “Are you a friend of Leni? Do you have the number of Leni? Call her. I will tell her what you’re asking me always.”

Five months later, Robredo received a text message ordering her “to desist from attending all cabinet meetings.” She called it the “last straw” in a series of efforts to prevent her from doing her job and resigned as housing secretary. Robredo said that as the people’s duly elected vice president, she would continue to perform her duties and, especially, her work for marginalized groups. She is well known as a champion of the urban poor.● ● ●

Then came demands for Robredo’s impeachment. The event that precipitated this clamor was a video presented in March during an unofficial side event at the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna. In the video, Robredo called the 7,000 killings in Duterte’s drug raids “summary executions” and deplored his impunity. Moreover, she said that victims of anti-drug police squads are allegedly beaten if they request a warrant, or they “have their relatives snatched as collateral.” The drug problem, she said, can’t be solved “with bullets alone,” and encouraged Filipinos to “defy brazen incursions on their rights.” Drugs, she said, are a “complex public health issue linked intimately with poverty and social inequality.”

The Senate president, citing Robredo’s “sustained” attacks against Duterte, accused her of being part of a triumvirate of legislators plotting to oust the president and destabilize the government. He especially criticized what he called her “false” and “misleading” claims in the video presented at the U.N.

In threatening to file an impeachment complaint against Robredo, the speaker of the House weighed in, saying that the vice president had committed treason by sullying the country’s reputation and betraying the public trust in an international forum. “Truth-telling is not an impeachable offense,” Robredo countered.

Robredo also declared that she had been warned of a plot to steal the vice presidency. “I will not allow the Vice Presidency to be stolen. I will not allow the will of the people to be thwarted.” She asked her supporters “to keep your courage because in a time of trouble and darkness, we need to be brave.”

Duterte initially joined in the call for her impeachment, claiming that Robredo couldn’t wait to become president, but quickly reversed himself, saying she has the right to free speech, and that removing her from office would damage the country. When I asked a source why Duterte was now playing nice, she answered, “He wants to be portrayed as benevolent, which he utilizes to undercut or disorient the opposition, but the attacks against Leni have been relentless. So this is a strategy! The other explanation is that he is just plain crazy and changes positions frequently.”

Under international law, there are several legal bases under which President Duterte could be held criminally liable. Because the Philippines has ratified the Rome Statute and is part of the International Criminal Court, Duterte’s clarion calls for extrajudicial killings in his drug sweeps could constitute incitement to violence. He could also be charged with instigating law enforcement—using the police and military—to commit murder. Additionally, the Doctrine of Command Responsibility holds superiors accountable for the unlawful acts of their subordinates, and Duterte’s public comments are admissions that he knew about these killings as well as about police involvement. Finally, the systematic nature of the killings and the fact that they number in the thousands could be designated as crimes against humanity.

There is no cause for optimism that justice will prevail soon. When Fatou Bensouda, the chief prosecutor of the ICC, warned Duterte that she was monitoring the situation in the Philippines and that he was potentially in violation of the court, he retorted that the Philippines might withdraw. “The International Criminal Court is useless. They [Russia] withdrew its membership. I might follow. If China and Russia will decide to create a new order, I will be the first to join.”

In February, the chief of the Philippines National Police instructed his members to stand down from their anti-drug operations. The order was invoked when a policeman who was part of a drug squad killed a South Korean businessman. Although embarrassed and angered by the incident, Duterte was more furious at the police for suspending their participation in the drug campaign. Once his chosen people, the police were now branded “corrupt to the core.”

Duterte then announced that the Armed Forces of the Philippines would join his “war on drugs.” As many governments do when they are short on reasons for justifying the use of military force, he said he would raise the threat from drugs to a national security level and that the “war” would continue. Although Duterte denied that he would declare martial law, militarization of any part of the citizenry is a common prelude to legitimizing political suppression and removing power from other branches of government. Thus far, the military has refused to lead the drug campaign unless it receives specific terms of engagement.

For many survivors of the Marcos regime, the militarization of the killings, as well as Marcos’ “hero’s” burial, brought back tormenting memories of rape, torture and brainwashing—the reliving of a historical nightmare that was all too familiar and painful.

At this writing, Sen. Leila de Lima is still incarcerated. In one of his obdurate moods, Duterte dubbed her an “odious character,” reiterating that she will “rot in jail.” During a visit to the city of Tacloban, he said, “If I were de Lima, ladies and gentlemen, I’ll hang myself.”

De Lima is continuing to fulfill her senatorial duties from jail and is fighting Duterte’s move to reintroduce the death penalty for drug offenders, along with a proposed measure to treat children as young as 9 like adult criminals. In March, she was honored by the U.S. journal Foreign Policy as one of its “Global Thinkers of 2016” for standing up to an “extremist leader.”

There is no sign that de Lima, Robredo and the other brave-hearted women of the Philippines, who are publicly challenging a vicious regime they deem responsible for the murders of thousands of Filipinos, will ever back down.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.