The Truth Behind Pfizer’s Paxlovid™

Our government spent billions of dollars on the drug based on Pfizer's say-so. But it was never clear that Paxlovid did anything useful at all. Image: Adobe

Image: Adobe

Editor’s note: The following story is co-published with Matt Bivens’ Substack newsletter, The 100 Days.

Here are some things we know about Pfizer’s brand-name antiviral elixir Paxlovid™:

- It makes everything taste terrible. “Paxlovid mouth” is discussed from Reddit feeds to scholarly journals. (“Dysgeusia” is the fancy medical term for this persistent foul taste in one’s mouth.)

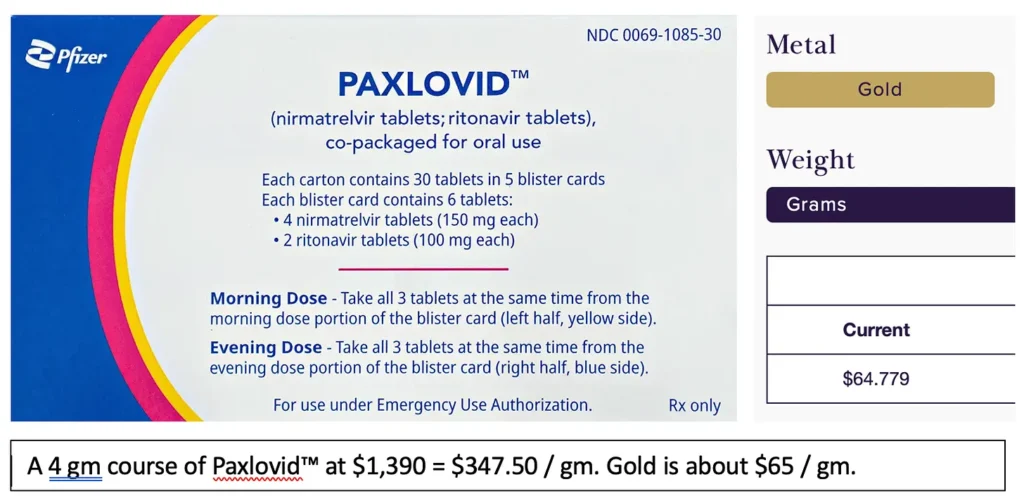

- It’s rapaciously priced. It’s now five times more expensive per gram than gold. Once upon a time, Pfizer sold a course of Paxlovid™ for $530, and as I noted back in October, by then we had already spent upwards of $18 billion for it — more money in a single year than had ever been spent for a pill in human history. But that was the pandemic special: As soon as the Feds stopped buying it, Pfizer all-but tripled the price. Now a Paxlovid™ course runs $1,390.

What we don’t know — still — is whether this is even a useful medication. Frankly, it’s starting to feel like a long con.

Paxlovid™ is Life-Saving! You Have to Say It’s Life-Saving!

The New York Times recently described Paxlovid™ as “stunningly effective in preventing severe illness and death,” and suggested that not embracing it continues to result in thousands of people dying. Apparently, the skepticism of doctors like myself about this drug is killing people.

As evidence, America’s leading newspaper cited an observational study in which getting Paxlovid™ was associated with fewer deaths. But to make big treatment decisions, doctors are usually hesitant to rely on observational studies. Those just look backwards in time at a population, and so can see associations but not necessarily causations. (Getting a five-day course of expensive Paxlovid™ was also associated with having some money, and quick access to a doctor, to mention some obvious confounders that affect a person’s overall health.)

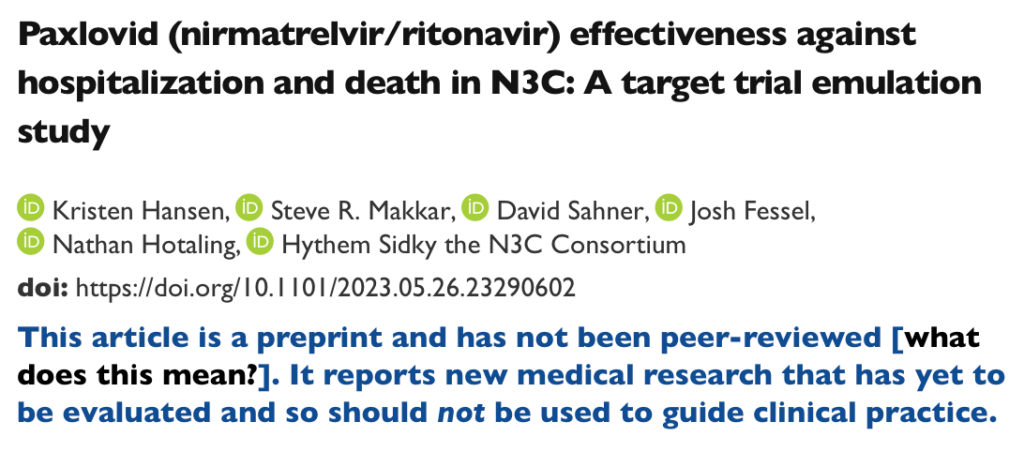

For an extra eye-roll, the study The Times cited has never even been peer-reviewed, and right at the top says it “should not be used to guide clinical practice”:

A more cautious review by the respected Cochrane group found that the antiviral cocktail of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir “may” — as in, “may or may not” — prevent deaths and / or hospitalizations, based on “low certainty” evidence. Cochrane delivered that lukewarm verdict through gritted teeth — because they know all too well that they’re being had again. It seems everyone, even Cochrane, continues to grudgingly observe the party line.

In fact, even when the news is frankly horrible for Paxlovid™, it gets nervously sugar-coated.

Consider a small study (observational, yes) published in Annals of Internal Medicine. This study out of Mass General Brigham used serial viral culture testing to investigate the rebound phenomenon — when a COVID-19 illness resolves, but then returns for an encore. The study found that a whopping 20.8% of those treated with Paxlovid™ “rebounded” back to shedding replication-competent viral particles after a course. Median duration? Two more weeks! Fully half of those rebounding, virus-spreading people had no symptoms.

This seems like it ought to seriously alarm the CDC, assuming they care about stopping the spread of viral respiratory infections. But no. In a recent review paper, CDC attacked the very premise of “Paxlovid™ rebound”. The U.S. President has reported he’s personally experienced this phenomenon, so has his former chief medical adviser Anthony Fauci, and the Pfizer CEO is telling people to just treat Paxlovid™ rebound with a second five-day Paxlovid™ course, “like you do with antibiotics” — but the CDC shuffles through a bunch of papers, shrugs, and says there’s no discernable correlation between taking “lifesaving” antivirals and developing some poorly-defined rebound symptoms.

There’s that word again: “Lifesaving”. In the appropriate context, everything from an aspirin to a Z-Pak™ could be lifesaving, yet somehow it’s only shrilly insisted upon when we’re talking about Paxlovid™.

A Z-Pak™ is a brand-name five-day course of the antibiotic azithromycin, which actually works and costs $10. No one ever talks about a “life-saving” Z-Pak™. Paxlovid™ is the brand-name five-day course of the antivirals nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, which “may or may not” work — but it is breathlessly praised as “life-saving,” and definitely costs $1,390.

Back to the viral cultures study: While 20.8% of the group who took Paxlovid™ suffered culture-positive rebound for two more weeks (ugh!), the group who fought off COVID-19 on its own rarely saw that rebound effect — it happened in 1.8% of cases and lasted only a median of three days.

This would seem to be catastrophic news for Paxlovid™. It suggests every fifth person or so who gets a course of this gold-plated drug wanders around for two more weeks shedding virus — and half of them don’t even know they’re doing it. Call them “Paxlovid™ super-spreaders.”

Yet when the public affairs department of Mass General Brigham announced this interesting new study, the apologetic subhead meekly noted that “Paxlovid remains a lifesaving drug”.

Does it, though?

Do we really all have to keep genuflecting before it?

All the Data We Haven’t Seen

So far, the only randomized trial evidence that Paxlovid™ is “stunningly effective!” (New York Times), or “lifesaving!” (CDC), comes from one study, EPIC-HR. That landmark New England Journal publication was Pfizer-run, start to finish — an appalling conflict of interest. Pfizer would go on to sell $18.9 billion worth of Paxlovid™ that year.

In other words: When Pfizer came up with a single study suggesting a positive result, it promptly turned this in to the federal government like an invoice, and was paid $18.9 billion.

Was it at least an amazing, transparent and convincing study?

Well, no!

EPIC-HR enrolled 2,246 unvaccinated, high-risk, and coronavirus-naïve patients who started nirmatrelvir-ritonavir or placebo within five days. But then, without explanation, the study only analyzed those treated within three days — which feels like statistics shenanigans. In any case, Pfizer reported nirmatrelvir-ritonavir reduced mortality by 1.3%. It’s often said the antivirals also reduced hospitalizations in this study — but actually, it reduced hospitalizations felt to be caused by COVID-19, a troublingly subjective concept.

This feels like ancient, Delta-variant history. Still, if we’ve got one study, and it showed Paxlovid™ reduced mortality by 1.3%, then we can say that at least then, it was lifesaving, right?

Not necessarily. Because we don’t only have one study. We have 18 studies.

When Pfizer came up with a single study suggesting a positive result, it promptly turned this in to the federal government like an invoice, and was paid $18.9 billion.

The Cochrane reviewers found two high-quality, reported studies: EPIC-HR, and a small Chinese trial reported in The Lancet. But they also identified 13 other ongoing studies, many of them Pfizer-backed, and three more — EPIC-HOS, EPIC-SR, and EPIC-PEP, all large studies operated by Pfizer — that were completed or terminated, but either way had long been radio silent. (Pfizer finally published EPIC-SR literally this week, in the New England Journal of Medicine. Short version: No statistically significant difference between Paxlovid™ and placebo, although 5.8% of those on Paxlovid™ suffered dysgeusia.)

For those struggling to keep score, that’s one positive study, EPIC-HR — against at least 17 studies that are either negative (the Chinese study and EPIC-SR), ongoing, or in limbo.

In medicine, when we speak of a study result being “statistically significant,” that’s defined as a result that would only happen by chance one time in 20. (In statistics-speak, that’s what a p value of 0.05 means: A 5% chance, or a one in 20 chance, that a result occurred randomly.)

This is a convention we adopted long ago, in an effort to protect against random results leading us astray. But when there are billions of dollars in play, it would be irrational of a pharmaceutical company not to lead us astray. All they have to do is fund 20 or so studies, keep quiet about 19 or so of them, and trumpet the 20th in a New England Journal article, and then use it (along with a never-ending churn of low-quality observational data) to hammer away at The New York Times health reporter until she goes national, and asks why doctors in 2024 aren’t moving more product.

The Forgotten Lessons of Tamiflu™

It’s as if we’ve learned nothing from the Tamiflu™ debacle. About 15 years ago, governments were being lobbied to stockpile oseltamivir for pandemic preparedness. Cochrane reviewers gave the drug a cautious thumbs up — much as Cochrane has just offered Paxlovid™.

But even as the British government spent half a billion pounds on Tamiflu™, Cochrane reviewers realized they’d been duped. Most of the data on this antiviral was hiding in files at the pharmaceutical company Roche, never to be published. And this was all perfectly legal.

It’s thanks to Cochrane that why we now know Tamiflu™ doesn’t really prevent influenza hospitalizations or complications, but certainly does increase vomiting, diarrhea and psychiatric symptoms.

Cochrane launched a years-long campaign to drag additional data about Tamiflu™ into the public domain — in the process, exposing how corrupted and broken the evidence-based medicine project had become. It’s thanks to Cochrane that why we now know Tamiflu™ doesn’t really prevent influenza hospitalizations or complications, but certainly does increase vomiting, diarrhea and psychiatric symptoms.

Of course, many years and many billions of dollars later, oseltamivir is still stockpiled by governments, still recommended by the CDC, and so on. Once bureaucracies have sunk billions of your dollars into a project, they don’t have much incentive to announce it was all an incompetent, sleazy screwup.

Perhaps now that we’ve been suckered out of billions of tax dollars for the second time — first with Tamiflu™, and then with Paxlovid™ — someone in government will finally reform the corrupt, secretive, dysfunctional system of conducting medical randomized trials.

Matt Bivens, MD, works at emergency departments in Massachusetts, including St. Luke’s in New Bedford and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. An earlier version of this article was published in Emergency Medicine News.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.