The Taliban’s Glossy New Front in the Battle for Hearts and Minds

It's sleek, it's glossy, it's in eloquent Arabic, Pashto and Dari, and it pours derision on American and NATO forces in Afghanistan; it is the brand new propaganda wing of the Taliban: not just Internet video of attacks on the Western armies in Helmand and Kandahar, but professionally produced magazines.It's sleek, it's glossy, it's in eloquent Arabic, Pashto and Dari, and it pours derision on American and NATO forces in Afghanistan; it is the brand new propaganda wing of the Taliban.

This article was originally printed in The Independent.

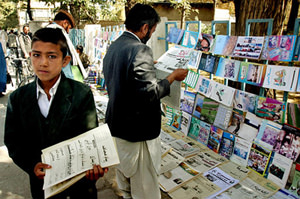

It’s sleek, it’s glossy, it’s in eloquent Arabic, Pashto and Dari, and it pours derision on American and Nato forces in Afghanistan; it is the brand new propaganda wing of the Taliban: not just internet video of attacks on the western armies in Helmand and Kandahar, but professionally produced magazines, carrying stories of the Taliban’s own “martyrdom” operations and the names of its dead fighters. For once, the cliché “well-oiled publicity machine” is correct.

Nureddin — or Abu Ahmed, as he preferred to be called, to denote that he is Ahmed’s father — is one of the creators of Al-Samoud, which roughly translates as “Resistance” or “Stay Put!” The latest front page of the Taliban’s monthly Arabic-language house magazine is adorned with photographs of a grim-faced General Stanley McChrystal, the US commander in Afghanistan, and the headline: “A surprise is awaiting the enemy in Helmand.” Inside, an editorial asks: “Is the battle of Marja as decisive as they claim?” while an article on casualties is accompanied by a coloured photograph of a British military cortège passing through the village of Wootton Basset.

Abu Ahmed is from Logar province in Afghanistan but his Arabic is fluent and his arguments straightforward. “In the West,” he says to me, “they say they have freedom of speech — so why shouldn’t we have freedom of speech?” We are talking over lunch in the weird company of three pink storks and a peacock that prowl the Afghan-Tajik-Uzbek restaurant in Islamabad where he has chosen to meet me, wearing a white robe, a white cap and a carefully combed beard.

His spectacles give him a student’s complexion, his arguments are exceptionally dry. When I ask him why he doesn’t produce an English edition of Al-Samoud and sell it to the 150,000 Nato troops in Afghanistan, he shakes his head with the words: “They are seeing everything live and they would have no time to read it — they are too busy fighting for their lives.”

Al-Samoud and the Taliban’s three other magazines in Pashto and Dari — the bi-monthly Morchel (“Trench”), Saraq (“Flame”) and Shahamak (“Dignity”) — are obviously produced on modern presses, although Abu Ahmed will not reveal their location. I suspect they are in Pakistan and receive a sharp look by way of reply. But they reveal two new characteristics: an almost obsessive attention to detail, and the new name of the Taliban. The group now calls itself the “Islamic Emirate”. That’s the original name of the country the Taliban governed until 2001, and its readoption is an attempt to free itself from the thieves and mafiosi in Afghanistan who call themselves “Taliban” but who have nothing to do with Islam or hostility to the Western forces in the country. Al-Samoud describes itself as “the Islamic monthly magazine published by the media centre of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan”. The Taliban distribute it across the Arab Gulf.

Abu Ahmed believes that the “Islamic Emirate’s” magazines will continue in their own right after Western forces leave Afghanistan. “Whenever we get news, we do not rush it into print,” he says. “We are checking this news with our sources in different provinces. Most of us are young people, doing different jobs — for the political as well as the military side of our organisation, although we are not fighters. As you know, the media is controlled by the West — so we decided to try and counter their propaganda. Of course, we also follow what their military says: details of their operations, attacks, and details of what they are going to do next — this is very interesting to us.”

The “Islamic Emirate’s” internet “Shariah radio” is also part of Abu Ahmed’s remit: tough, hard-edged programmes intended to appeal to rural Afghans. “We have proved that Afghans can adjust themselves to learning about the situation,” he says. “Most of our websites are run by professionals. That’s why the Americans have tried to block them so many times, using different “gates” in Afghanistan and other areas — but we have been able to unblock them every time.”

Abu Ahmed admits that illiteracy presents a major problem — he doesn’t mention, of course, that the Taliban made a major contribution to this by banning female education — but says that Afghans who can read pass on the information in the magazines to all members of their families. He says that women are now involved in the magazines’ production and in the military struggle. “From our point of view, a woman is the property of one person — if she is my wife, she is mine. But our women are cleaning the Kalashnikovs, carrying ammunition. In Kandahar, they are carrying mines under their burqas because that way they cannot be checked.”

Al-Samoud in many ways mimics Western propaganda. The “military commander” in Helmand, for example, is quoted as saying that “the mujahedin (holy warriors) are fighting the enemy in Marja with high spirits”. The latest issue carries special features on the 20th anniversary of the Soviet retreat from Afghanistan, an interview with the rebel commander Jalaluddin Haqqani, and America’s use of dogs to torture prisoners (a practice employed at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison). One story claims that US servicewomen are used to abuse and humiliate Taliban prisoners. There are even profiles of hundreds of Taliban “martyrs” — identifying, for the very first time, with names and photographs, those who have died fighting Nato. Saad al-Haq (code-named “Jenaan”), for example, died in a follow-up attack against the Kandahar Nato base on 20 March 2008. Mullah Abdel Manon was killed on 14 September of the same year “in a martyrdom attack” against the same “Crusader fort”. Maulawi Abdul Salam died last year during an attack on the fort of Zaal in Moudiriya.

Oddly, Al-Samoud even names its editorial board — Hamidullah Amin is the “president of the board of publishing”, and Ahmed Shah Halim is the chief editor, assisted by three journalists, Ikram Maiwandi, Salahedin Momand and Arfan Balchi. Pakistani journalist Rahimullah Yusufzai keeps a keen eye on the Taliban’s propaganda. “Their magazines and websites are targeted at different audiences,” he says. “They are keen to tell of their battlefield achievements — that is how they will impress their donors. Their articles didn’t used to be so good, but they’ve improved tremendously. Now they are very well written, though of course one-sided. Nowadays, the magazines even contain poetry.”

The propaganda wing of the Taliban calls itself the “Information and Cultural Department” which is run by Abdul Hai Mutmain from Zabul. He was once head of the Taliban’s “information department” in Kandahar where, though not a minister, he was close to the Taliban leader, Mullah Omar. “The Americans say they came to save Afghanistan from war,” Abu Ahmed continues. “But this war is only harvesting our civilians. The Americans are coming with their war planes and killing civilians. The Americans see everything from the sky — surely they can tell the difference between two or three cars of civilians and military targets? So this means they are either doing it deliberately or they do not know how to fight.”

And as the peacock on the lawn tries to attack the remains of our food, Abu Ahmed adds his own personal warning. “My father and grandfather told me: ‘You have to fight the Russians’. Now I tell my son: ‘You must fight the Americans’. The first thing we teach our children is ‘Allah’. The second is fighting the Americans. As for the British, they are making the same mistakes they made before — they will experience a second Maiwand.”

Afghan forces routed a British army at Maiwand in the Second Afghan War. Only later, however, does Abu Ahmed tell me that his son is just three years old. By the time he grows up, I ask him, doesn’t he think the Nato forces will have left Afghanistan? In return, I get a thin-lipped smile and a raising of eyebrows. I suspect that means they will be staying.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.