The ‘Slave Side’ of NFL Sundays

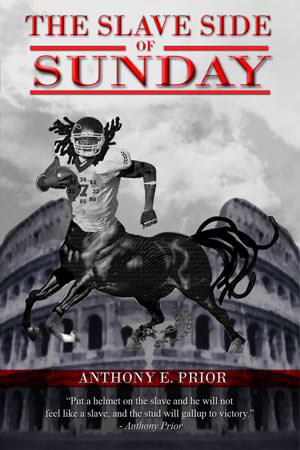

In his new book, "The Slave Side of Sunday," former NFL player Anthony Prior writes about the legacy of racism in professional sports "We are not looked at as leaders, rather, just a labor force where the money is generated Plantation capitalism is still alive today," he tells Truthdig contributor James Harris (Audio and text interview with the author) .

In his new book, “The Slave Side of Sunday,” former NFL player Anthony Prior writes about the legacy of racism in professional sports. “We are not looked at as leaders, rather, just a labor force where the money is generated. Plantation capitalism is still alive today,” he tells Truthdig contributor James Harris. What follows is an uncut transcript of their conversation. (Or jump to our audio version.)

James Harris:

Here we sit with Anthony Prior, former NFL player. He’s played for the greats, like the Minnesota Vikings and the Oakland Raiders, and he’s also spent some time in the Canadian Football League. He joins me today, though, as the author of one of the more controversial books out there. The book is called “The Slave Side of Sunday,” and you will be able to buy it [March 9]. One way to do that is through Stone Hold Books. We’ll be talking more about that as the interview goes on.

Anthony, Welcome to Truthdig.

Anthony Prior:

I want to thank you for having me.

You say after 11 years of pro football, you’re well equipped to discuss the souls of African American players who have transcended the game to a billion-dollar market, but yet have no chance and no voice within the industry. You say the black athlete should have the right to express his concerns, whether to his team, community or his country — without suffering career suicide. Can you elaborate exactly on your meaning there?

I have read a lot of black sports stories and one that really stuck out was written by Harry Edwards, and he said that black players in the ’60s were united through their oppression, and the black athletes of today are divided through their successes. So I took from that and I explained it in more of a contemporary sense–and based on my 11-year experience, the things I have witnessed, how players have become more submissive, more obedient; they have become more like automatons–a mechanical device resembling a human being. That’s the conflict I witnessed.

But the conflict today is–what the conflict means is serious disagreement. The conflict is, too many black athletes believe they are going to the pros. They have this illusion that because they can run, throw or jump, they’re guaranteed an opportunity in the sports industry. This is creating a crisis, a time of severe difficulty. The crisis today is the lack of knowledge and information, on an informative basis, a spiritual basis. We have a crisis when players don’t make teams on a pro level and start engaging in crime and a [garbled] lifestyle. We have a crisis when we see grown men fighting like slaves on a plantation before the game even starts. These are moral issues that must be addressed. We have a crisis when, in 1946, the NFL was forced to integrate and black athletes have taken it to a billion-dollar-plus market, yet have no owner in the industry. We are the record-breakers and trendsetters, yet we have no guaranteed contracts in the NFL. And the owners in the NFL are guaranteed profits annually. Since the players have ignored these aspects of the game, we are not looked at as leaders, rather, just a labor force where the money is generated. Plantation capitalism is still alive today.

So, the resolution. Well, resolution means a firm decision. Every black athlete must realize when pursuing a pro sports career, his fate, his talent, his determination, is in the hands of a committee that’s holding his lottery ticket–a lottery ticket that he didn’t print. Your career is in the balance of people who never even put on a helmet. Every player must pursue sports as a hobby, and get all you can out of it before it gets all it can out of you. Because I’ve witnessed this beast, this sports institution that can take the life right out of a grown man. And I’ve seen lives destroyed, because players felt they couldn’t do nothing else but be a physical beast on the field.

So what was your hope giving it the title “Slave Side of Sunday”?

Before Malcolm X was assassinated, he was interviewed, and a reporter asked Malcolm, “If you could do anything different concerning your movement, what would it be?” I quote Malcolm X: He said, “I wish I would have woke the people up first, before I tried to organize them.”‘ You cannot direct a sleeping giant, so an athlete today, he needs to be woken up. He’s sleepwalking, he’s such a powerful force that could change the entire fabric of this nation. Anytime you created a billion-dollar-plus market, you should first establish a voice. And we don’t have that today. This is what I call “mental slavery.” Slavery is not limited to bondage and chains. You got parents, preachers, teachers, coaches, fundamentally imposing these characteristics on these young black children in America, that without sports, you’re going to amount to nothing. Every black athlete we see on a professional level, he is one in 12,000. There are two things that can’t lie: That’s God and mathematics. So my objective is to go around the country and educate through sports, and let the youth know that if you don’t get all you can out of sports, and it turns around and gets all it can out of you, there’s going to be hell to pay.

In the NFL, 65% of the player force–as you know and well document in the text–are black. Six percent of the general managers are black. No–as you noted–no owners in the NFL are black. We can take a peek over at major league baseball and look at the managers over there. There are virtually none. We can look at the ownership again. There are very few, or none. And this is true of all of the leagues. Blacks have not managed to break into ownership or management. Is the NFL responsible for recruiting and maintaining a significant level of blacks in the league? Should they be held responsible for that?

I believe history explains a lot of things. From 1934 to 1945, blacks were banned in the NFL. But from there we created the Negro Football League. We were establishing ourselves, we were laying a foundation. You had a lot of black outstanding college athletes during that period that were playing in the Negro League. They didn’t care about going into the white NFL. But after WWII and the contributions of blacks in the war, it necessitated a whole new responsibility in America. A lot of blacks were speaking up, we wanted to integrate and we wanted a lot more of the American dream. So the black press pressured the NFL; the Negro League pressured the NFL, saying we want to become your competitor, so the NFL had to re-integrate, because they knew they couldn’t win. So what happened there, we lost our owners, our trophy cases, our fight songs, we lost coaches, general managers. And then came in the architect of the black athlete today, because today we’re just looked at as physical specimens. Those who prescribe your knowledge determine the range of your thinking. As soon as little Tyrone or little Pooky starts running, jumping or throwing something, the first thing we say in our minds is, oh, he’s going to get us out of this present condition, he’s going to be an athlete, he’s going to make a million dollars. But the owners of the institutions, the general managers and presidents, they’re leaving their kids’ wealth in a legacy. But my kids, with that mentality, will always have to prove themselves. So this has become fundamental. Because any time as a young black man, you don’t see black grown men in a position of leadership, you don’t feel you can lead. The only thing you see us as is a labor force, just like a slave on a plantation. And that mentality holds strong today. A lot of players feel they can’t be owners, they feel they can’t be coaches and general managers and scouts and work in the administration and make decisions, because they feel decisions have always been made for us–and against us.

It sounds to me like you’re saying that the history of the NFL has led it to a racist presence now, and that this is built into the framework of the league.

Absolutely. Racism in the NFL exists in the 21st century. You see, there was one point in time black players were a little bit above 70%, and today we’re at 65, you see, this is all by design. Because once they get our numbers down to 50%, there’s going to be no argument for the black athlete. Because the white athlete, he’s represented very well. He gots 32 owners, he gots 25 of the head coaches, are white. The administration, 89% are white. He’s represented very well. But in my opinion, the white athlete is not made to be the black man’s equal on the field. But as long as you’re being represented well, at high places, you know football’s a team sport and team sports can be manipulated. You can take a below-average player and surround him with great players to compensate his weaknesses. And that’s what’s going on today. That’s why the white athlete is present. He’s present with steroids, and he’s present with people in high places making decisions for him, allowing him to play on the field. Just like arena football: You condense the field, you don’t gotta be that fast, you don’t gotta be that agile. That’s allowing more white players to play.

More people can become competitive. And it sounds like similar things are happening in the NBA. The game is changing in such a way that a different level of competition has become possible.

Absolutely. You got a lot of white players that are outside shooters, and that myth that black players are only good enough to dunk and rebound. When you control the game, you can put people you want on the game. Sports–team sports–is just like a chess board. As long as the weak go up against the weak, and the strong go up against the strong, everybody looks good.

[Laughs] Very true. Very true. Anthony, how different is the argument you’re making in your new book, “The Slave Side of Sunday,” how different is your argument from the traditional one, that said–where black people were calling for their 40 acres and a mule, which they were promised, of course, by the government. How different is your argument from that? What solution do you have? Give me something that listeners, that players can be proactive about in solving this problem, as opposed to something that they would be reactive about? [Like:] “Hey, the NFL isn’t giving me this, they aren’t doing this, and we’re suffering as a result of it.”

You know what I would love to see?

What’s that?

And I believe a lot of other players would love to see? Have a black players union where our voice can be represented, our interests can be heard. Any time if you’re the labor force you’re gonna need somebody speaking for you. I know Gene Upshaw–.

Who is the director of the players union and is a black man. How do you think he’s done so far? I know there’s a far cry between having one black man as the all encompassing leader of every player in the NFL, versus what you’re suggesting as having a specific union that deals specifically with issues for black folk.

Gene Upshaw has been there for 23 years, he has a stellar record. I think we need to change today; you know, we’re in the 21st century, we need some new ideas, a fresh face, fresh ideas. And I’d like to see a change.

What kind of change, anything specific?

I would like to see somebody that is more boisterous, somebody that is more willing to speak out on racism and hypocrisy that is so prevalent in the NFL today, and make–let’s see some real changes. I know they got the Rooney rule.

Which is, what is the Rooney rule?

The Rooney rule is when a coach [position] is available in the NFL, they have to interview one minority. That’s good, it can kind of go both ways. Even though a franchise in the NFL already knows which coach they want to hire — his buddy, which is white, that’s in the other room — let’s go ahead and fly in this black coach, let’s just interview him, pay for his hotel and his airline flight, interviewed him, we did our quota, OK, bye, then we can go ahead and hire who we originally wanted to hire.

Sure.

That’s not good enough. Allow players to vote on their president, their head coach, on their head chief in charge. Let players have some say-so, and I guarantee you’ll have more black coaches in the NFL, whether it’s head coach or assistant coach. Players vote on our peers, to go to the Pro Bowl, who’s good enough [for] the Pro Bowl. How come we can’t vote on our coaches, who we think that can lead us to the Super Bowl, who can lead us to the promised land.

Anything specifically from the text that you want to share related to that?

Just like black players having their own democracy on the football field. If we’re 70% of the NFL, we generate the money, we’re the oil, we’re the engine behind this industry, because without the black sweat on Sunday afternoon, leagues would crumble. The NFL would crumble, so we need to have more say-so. We need to have our own democracy.

So you’re not calling for the NFL to do this. You’re calling for black players, black managers and black money, which there’s been over 500 players to cash out a million dollars in this game. I’d be calling for those guys to make some changes.

Absolutely. So in that respect it’s not the “40 acres” argument, it’s kind of a black community introspective, it’s saying, hey, this is what we need to change and this is why we need to change it. Kids are affected, athletes are affected, and ultimately the black community is affected by this lack of action in the NFL.

Absolutely. Gene Upshaw cannot make no changes. The person that can make the chance is the assembly of black players. Individually people can shout, and have rhetoric and talk all day long. But when you assemble, you come together as a group, that’s powerful.

I’m talking to a gentleman by the name of Robert Morris who is the founder and CEO of a group called Center for Diversity. He says– and I think you guys agree on this– he says that black people need a shift in mind-set. His quote is that blacks collectively need to understand that the NFL is about profit and not about humanitarian efforts.

So I think Morris is saying that it is about capitalism, it is about money, and so these people put money in the hands and control of teams in the hands of people they’re close to and people that they grew up with. I think that the problems you mention with regard to the lack of diversity and the lack of true commitment to getting black people in there is problematic, just like affirmative action has become problematic in that people are trying to fill quotas.

People are trying to respond to things like the Rooney rule –.

Yeah. (laughs)

That’s where affirmative action goes wrong, that’s where diversity programs go wrong. How could the NFL solve that political issue, how could they move past just saying “hey we’re gonna interview a black guy” into an area where they’d actually consider a black guy?

We’ve got to take some of the control out of their hands and into the hands of players, to have a little more of a balance when it comes to hiring coaches, when it comes to hiring a leader to try to take team into the Superbowl and win a championship.

If I’m a player, man! I wanna have some say-so of what coach and what philosophy he’s bringing in. You know, when the head coach and the team is about to sign a free agent, a high-profile player, there’s dialogue between the coach and players: “We’re gonna bring him, what do you guys think about it?”

It’s the same thing with Donovan McNabb and Terrell Owens they were talkin’ at the Super Bowl. Dovovan was puttin’ in word to the coaches and the coaches were talking with teammates–“we’re gonna bring in Terrell Owens”–and everybody agreed!

So we need to have that same opportunity when a coach comes in, we gotta have a better relationship with the president and the general manager. He needs to come down and say we’re gonna hire a few coaches, we got five on our list, and then the president and the general manager can address the team, with the coach’s qualifications, his philosophy, and see if he’s the best man for the job–based on his qualifications, not on his skin color.

Why don’t more players say “I want 10 million dollars, plus 6 million dollars of equity in this team?” Why don’t more players actually have written into their contract–I want team equity–so then it becomes a shared ownership, then they start to care about some of the decisions that are made?

They’re involved in the managerial process, they’re involved in the capitalist process, and it’s not just a social argument, it’s not just “do this for me because I get help or I need help or I was discriminated in the past,” it’s because I have equity in this team and I care about this team and I value this team. It surprises me that more players haven’t done that. What do you think about that?

Too many players have that impoverished mind, you know? They feel they’re money’s gonna run out, so they gotta get all they can while they can, while they’re able to perform. They don’t have that type of mind-set. That is something that can be educated to the young, the teenagers coming up.

The players that are presently in the NFL today–you’ve got a few warriors here and there, you got a few that have a consciousness to speak out, a consciousness for better compensation, but they feel that they are gonna be blackballed.

That’s why you gotta have a voice, you gotta have something separate from the NFL players association. You gotta have a black voice, you gotta have a black players association so issues like that policies can be written in bylaws, that can be effective.

Until you have a bylaw, you have a policy, ideas are just great [gravy].

Can a group of black NFL professionals really come together and really make a change?

Absolutely. I think it would be great to get some ex-players, that have contributed very well to the NFL, establish that outside voice, be able to have policies to where some of the profits these NFL owners have –they could go into where they recruit their players, some of these ghettos in America where they’re getting their prize-winning machines, you know start developing some of these communities, you know, policies like that.

That way everybody benefits. Because right now we got great individual achievement in our communities and our cities, but collectively, black people, we’re not–we have some, that collectively have a strong voice collectively gettin’ things done, but we need to see it more on a bigger scale.

And perhaps the book, “Slave Side of Sunday,” will be a start to that coming together.

Just last night I was hosting and I gave a presentation at the Fontana NAACP viewing party of the NAACP Image Awards last night, and there was over 200 people there, really first class. I got a chance to really let loose and let ’em know what’s coming and I had over 50 people pre-order the book, so they wanna put a book show on for me, so, you know —

It starts with the community first, and if the community doesn’t back you, you’re not gonna be heard. So right now the campaign has started, and thanks for you giving me this radio interview. It all just gets the ball rolling.

The “Slave Side of Sunday,” Stone Hold Books, tell us a little bit about who publishes that book.

Stone Hold Books, that’s my publishing company. I started it in 2003, because when I first wrote a proposal, I sent my proposal out to major publishers, and a few got back to me, but they said they wanted to turn my story into a fiction story and change the title.

They said it’s gonna take about a year, year and a half to get the book out.

So I said to myself no way, can’t nobody tell my story better than me. I’m not gonna put my dream, my vision on hold for nobody.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

(Above: Anthony Prior)

(Above: Anthony Prior)

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.