The Other 43 Percent

Hollywood’s gender gap is most apparent with regard to female filmmakers, but their prospects weren’t always as bad as they are today. (Part 1 of our five-part series.)

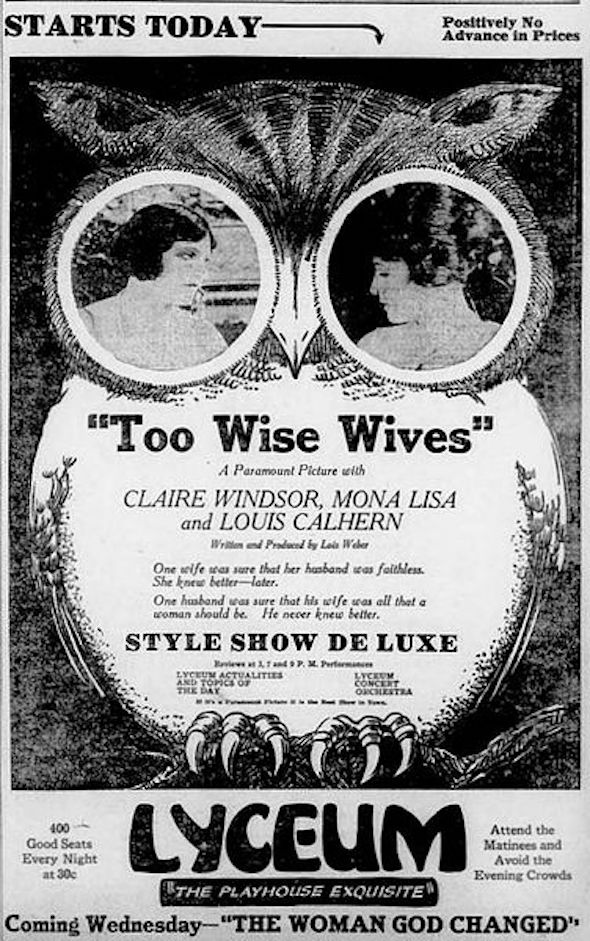

A 1921 print advertisement for Lois Weber’s “Too Wise Wives.” (Wikimedia Commons)

Editor’s note: In October 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission began investigating Hollywood’s gender gap. Before it delivers its recommendations to the Trump administration, Truthdig contributor Carrie Rickey considers the historic accomplishments of women behind the camera, how they got marginalized, and how they are fighting for equal employment.

This five-part Truthdig series is published in partnership with Women and Hollywood and Chicken & Egg Pictures. Click here to read Part 2, here for Part 3, here for Part 4 and here for Part 5.

It’s a paradox, akin to why women receive 47 percent of law degrees but represent only 35 percent of those working in legal professions. And why, though 42 percent of architecture-school graduates are women, they are just 25 percent of practicing architects. Why do females make up between 33 and 50 percent of film-school graduates but account for only 7 percent of working directors, as Martha Lauzen, professor at San Diego State University, reports in her annual “Celluloid Ceiling” analysis of women on the screen? What happened to the other 43 percent?

In American film (a kind of parallel universe to American life), this asymmetry results in an asymmetry on screen, in which men outnumber women two to one. According to Walt Hickey at fivethirtyeight.com, in movies the workplace is more male—and more sexist—than in reality. “This is an industrywide problem that requires an industrywide solution,” says Lauzen, who has been tracking the numbers for 20 years. “The heads of the studios dutifully mouth that they want change but have yet to introduce any programs or make hiring decisions demonstrating true leadership or vision.”

In October 2016, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), prompted by American Civil Liberties Union findings that “female filmmakers are effectively excluded from directing big-budget films and seriously underrepresented in television,” began investigating Hollywood’s gender gap.

Maria Giese, the filmmaker who brought the issue to the attention of the ACLU, said she doesn’t know what might happen under a Trump administration, but “I hope the ACLU will prioritize the investigation, and not see it as trivial compared to all the other immense challenges they face. I hope they will see it as being foundational to advancing all other civil rights.”

* * *

When the movies were born in 1896, female filmmakers were central to the new art form, entering the industry in great numbers, both in front of the camera and behind it. They pioneered new forms and techniques—and a different kind of content from that produced by their male counterparts.

Alice Guy, along with the Lumière brothers and George Méliès, was one of the founders of French cinema. From the first, she broadened the scope of the infant medium. Believing that movies could do more than document real life, Guy proposed to her employer, Léon Gaumont, that she make a “story-film.” The result was “The Cabbage Fairy” (1896), a whimsical rendition of how babies are born, made when she was 23. It may well be the first narrative movie. Guy did not take credit for that, but did credit herself as the first female filmmaker and the first to own her own studio. She would write, produce and/or direct more than 1,000 films. While a motif of her mature films is the inner lives of her characters, she was as much about form as she was about plot.

First in France and then in the United States, Guy introduced cinematographic methods such as double exposure and running the film in reverse. She also made many “talking pictures,” called “chronophones,” synchronizing the movie with a sound recording, and produced hand-tinted features, which are among the earliest color films. In 1907 Guy and her husband, Herbert Blaché, came to the United States. After she delivered their first child, they worked together at American Gaumont, where she was known as Madame Blaché. In 1910 she founded Solax, her own studio, in Flushing, N.Y., and soon built a state-of-the-art studio in Fort Lee, N.J.

Over her career, the filmmaker—now known as Alice Guy-Blaché—worked in every genre: comedies, dramas, Westerns, and even a biblical epic, “The Life of Jesus” (1906). Many of her films feature resourceful child heroes and even more boast resourceful female leads. She made the earliest extant narrative film with an all-black cast (“A Fool and His Money”) and among the first movies on the themes of spousal abuse and infidelity. Although her directing career ended in 1920, she enjoyed a more successful, prolific and longer career than most of her male contemporaries.

Alas, in what is prophetic of the contributions of many female filmmakers, only a fraction of Guy-Blaché’s work survives. But in recent years, films of hers gone missing are being found, reflecting the growing interest in cinema’s founding mothers,.

“When Alice Guy-Blaché died in 1968, she thought three of her films were extant but couldn’t locate any. In the early 1990s, some 40 were known,” says Joan Simon, curator of the 2009 retrospective of Guy-Blaché’s work at New York’s Whitney Museum. “By the time of the retrospective, 130 were extant—we screened 90 over a three-month period. Now, 140 have been identified.”In 1910 only 18 percent of American women worked outside the home. That year, as Guy-Blaché directed a film at American Gaumont in New York, she noticed an attractive actress, a onetime missionary, who would use the movies as her ministry. Her name was Lois Weber, and she would become one of the most significant filmmakers of her generation, on a par with D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille. It would be nice to think that Weber was inspired to become a filmmaker by Guy-Blaché’s example or, perhaps, that the Frenchwoman mentored her. But it would not be correct.

Guy-Blaché recalls in her memoir that Weber “watched me direct … and doubtless thought it was not difficult.” For her part, Weber credits Herbert Blaché for “broad-mindedness” and for giving her “every encouragement” as she transitioned from an actress to a screenwriter and director along with Phillips Smalley, her actor/producer husband.

Both female directors agreed that women had directorial advantages that men sorely lacked. Guy-Blaché believed that “women’s authority on the emotions” made them more skilled in working with actors. A woman, Weber said, “more or less intuitively brings out many of the emotions that are rarely expressed on the screen. I may miss what some of the men get,” she observed. “But I will get other effects they never thought of.” Both Guy-Blaché and Weber proved that women were as imaginative and powerful behind the camera as in front of it.

Another practice these two women shared was a commitment to writing as well as directing their movies, a dedication held by many female filmmakers throughout history. For women, writing scenarios was a primary path into the movies. According to Weber biographer Shelley Stamp, records suggest that during the silent-film era, women wrote half of the scripts. This is a much higher number than at any time in film history, as well as a rare example of gender equity.

Weber starred in her early shorts, making her one of the first actor/directors. With “The Merchant of Venice” (1914), she became the first American woman to direct a feature film.

Many, if not most, of Weber’s credited 130 films focus on the relationships between men and women and the particularities of female experience. “Sunshine Molly” (1915), which she co-directed with Smalley, is the story of sexual harassment in the workplace. It pivots on the harasser’s shame, and then transformation, when he learns of Molly’s rape by a prior employer. Boasting distinctive photography and visual effects, this social-issue film told from the points of view of the perpetrator and the victim blazed the trail for Weber’s future films depicting the gap between a character’s actions and values.

“Hypocrites” (1915), the film that secured Weber’s reputation, is a portrait of a clergyman troubled by the insincerity of his parishioners. After his sermon, he takes a nap and dreams that “the naked Truth” (the allegorical figure, wearing a nude body-stocking) holds up her mirror to show the congregants’ rationalizations about sex and politics. The film was an enormous critical and commercial success. It cost $18,000 to make and netted $133,000—roughly seven times its investment. Its success earned Weber and Smalley a contract at Universal, where they had worked earlier in their film career.

Female filmmakers were active outside the Hollywood system as well. Film scholar Pearl Bowser notes that African-American cosmetics pioneer Madame C.J. Walker produced training and promotional films about her cosmetics factory in Indianapolis. Madame Toussaint Welcome, personal photographer of Booker T. Washington, produced a film about a unit of black soldiers fighting in World War I.

In 1916, Weber was one of seven female directors on Universal’s payroll. The others were Ruth Ann Baldwin, Grace Cunard, Cleo Madison, Ida May Park, Ruth Stonehouse and Elsie Jane Wilson. Contrast that with Universal a century later; in 2016, there were 1.5 female directors: Jerrica Cleland, co-director of “Ratchet & Clank,” and Sharon Maguire of “Bridget Jones’s Baby” fame.

Compare Universal of 2016, marketing the comedy about the klutzy singleton uncertain of the paternity of her fetus, with the same studio 100 years ago, when it released Weber’s incendiary “Where are My Children?” (1916), a pro-contraception, anti-abortion drama produced as Margaret Sanger proselytized for what she called “voluntary motherhood.” Made at a time when distribution of birth control was a felony and when movies did not enjoy First Amendment protection, the film “encountered significant problems with censorship,” Stamp says of this early endorsement of some reproductive rights.

Despite the censors, it enjoyed tremendous success. The same cannot be said for “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle” (1917), her second birth control-themed movie, and one in which she also stars as a birth control advocate arrested and imprisoned for circulating information on contraceptives. By the middle of the ’teens, Stamp says in an email, “Weber was simply one of the “top three minds” in Hollywood, alongside Griffith and DeMille, a filmmaker whose finely crafted films on hot-button social issues generated critical acclaim and tremendous profits for the studio.When Weber decamped from Universal in 1917 and created her own studio, her distribution deal with her former studio guaranteed her the highest salary of a Hollywood director: $250,000 per year (that translates to $4.6 million now). Her independence coincided with a change in media coverage: The press was more likely to report on her female stars than on Weber or her films. The perception of her shifted from filmmaker to star-maker.

She continued to make stars, helping transform a beauty-contest winner named Ola Cronk into Claire Windsor, radiating intelligence as the leading lady in the director’s most accomplished movies, all made in 1921. “What’s Worth While,” “Too Wise Wives,” and “What Do Men Want?” looked at marriage through the lens of class and gender. They are startlingly candid about the different expectations partners can have of courtship and wedlock. Windsor also stars in “The Blot,” the movie many consider Weber’s masterpiece. It features Windsor as a shabby-genteel librarian who transforms a hedonistic collegian (Louis Calhern) into a caring person.

Sadly, as American women gained the right to vote in America (1920) and lobbied for an Equal Rights Amendment (1923), female directors lost momentum. When Republican candidate Warren Harding was elected president in 1920, did his platform of a “return to normalcy” signal that women’s progress in the professions would be reversed? Though Weber would continue to direct through 1934, her output after 1922, when Lois Weber Productions ceased to operate, was sporadic. She and Guy-Blaché hit an invisible wall. Some say that studios, worried about entrepreneurial female stars such as Windsor and Mary Pickford, bought out independent filmmakers and began vertical integration, achieving control over human assets by keeping them dependent.

Stamp hypothesizes that “by the early 1920s, the female star had … come to replace the female director as the iconic emblem of women’s place in Hollywood.” Careers were lost, as were opportunities for movies made from female perspectives. The final shame: Guy-Blaché and Weber were effectively erased from movie history, “forgotten with a vengeance,” says historian Richard Koszarski. It was not until the 1970s and 1980s that scholars wrote them back in.

As they began to recede from view and memory, a young woman who had left the University of Southern California to drive for the Volunteer Ambulance Corps during World War I found herself “holding script”—as a continuity girl, in 1920s parlance—for a movie called “Stronger than Death” (1920). It was co-directed by none other than Herbert Blaché. Her name was Dorothy Arzner.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

Alice Guy-Blaché in 1912. (Wikimedia Commons)

Alice Guy-Blaché in 1912. (Wikimedia Commons) Lois Weber, c. 1916. (Wikimedia Commons)

Lois Weber, c. 1916. (Wikimedia Commons)

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.