The Maker Movement: Tinkering With the Idea That College Is for Everyone

Increasing numbers of Americans have been seeking the satisfaction that comes with a trade. But vocational education needs some rethinking.

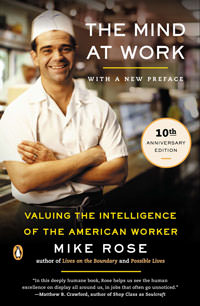

The following is adapted from the new preface to “The Mind at Work,” a modern classic about education and labor.

My plumber, Billy, has just finished clearing my bathroom sink, and we are leaning against the counter, talking. Billy is in his early 40s, self-employed, a clean cut, thoughtful guy with heavily muscled forearms from all those years of turning a wrench. He and his wife of two years are closing on a house in the canyons, and he pulls out his cellphone to show me a few pictures, describing the wooded surroundings that we can’t see. He is deeply, quietly pleased. As was the case with many blue-collar workers, Billy felt the effects of the Great Recession; people put off repairs as long as they could and tamped down any thoughts of renovation. But toilets continue to clog, old pipes crack, tree roots wreak havoc on plumbing, so Billy had steady work, and it has picked up as the recession slowly eases. As long as his body holds out, there will be work for Billy to do.

Plumbing provides for Billy what the trades have long provided: a skill that enables you to make a living, have a degree of independence, in some cases be your own boss. Your trade gives you a recognized place in the social order and a personal sense of value — you can make and fix things, you are needed. You are also vulnerable, of course, to the slights of occupational status, to physical injury, to changes in technology, to fluctuations in the economy — construction workers were devastated during the recession. And your work is hard and often dirty. Billy does not relish crawling under houses.

When Billy was showing me the pictures of his new house, he noted that there were some things that needed repair, the kitchen particularly. But, he smiled, “I can do that. That’s what I do.” Billy will be taking his skill home, his handiwork evident on the finish on the cabinets, the fixtures on the sink.

Over the last 10 years or so, increasing numbers of Americans have been seeking the satisfaction that will come naturally to Billy as he works on his house. We seem to have discovered the pleasures of working with our hands — or at least of using products that are handmade or manufactured on a small scale, artisanal, locally produced. There is a Makers Movement and Make magazine, and a related Do It Yourself movement. In education, there is growing interest in making and “tinkering” to foster, in one organization’s words, “imagination, play, creativity, and learning.” As opposed to some anti-technology expressions of this hands-on spirit in the modern West, our era’s movement embraces technology — computers and digital media are as much a part of the Makers Movement as woodworking and quilting. The same holds for education, which wants to draw on young people’s involvement in computer technology and social media.

For some, making, tinkering, fixing are part of a political philosophy and a social movement: a reaction to corporate domination and mass production. In education, making and tinkering are a reaction to traditional school-based learning, textbooks, fixed lessons and standardized testing — intensified in our high-stakes accountability, No Child Left Behind era.

Though ours has a contemporary cast to it, movements such as making and tinkering are not new. During the 19th century high-water mark of the Industrial Revolution, there were similar reactions and a desire to return to craft and the work of the hand, epitomized in England by William Morris and manifest in the United States by the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts Movement, one legacy of which is the Craftsman style house. In education as well, various European and American educators sought release from the drudgery and disconnection of the typical school lesson built on textbooks and recitation. There was an attempt to include in all children’s curriculum tasks drawn from the farm and the skilled trades. “Throw in the fire,” proclaimed one passionate advocate, “those modern instruments of torture, the spelling and defining books.” So our discovery of making and tinkering is a rediscovery, one that seems to emerge in reaction to social and economic trends that leave Americans yearning to use their hands, to manipulate tools and feel wood or metal, to wear or eat or look at things that didn’t zip down a conveyor belt.

By and large, the Makers Movement is a middle-class movement. Working-class folk have not had the luxury of discovering making and tinkering; they’ve been doing it all their lives to survive — and creating exchange networks to facilitate it. Somebody across the street or down the road is a mechanic, or is wise about home remedies, or does tile work, and you can swap your own skills and services for that expertise.

Turning this social class perspective to our schools, educational researcher Shirin Vossoughi points out that making and tinkering have been central to vocational education for a century, yet they never carried the status or buzz they do now that they are more the domain of middle-class kids — and include sexy digital technology. To their credit, there are educators — and this includes Vossoughi and others at the San Francisco-based Exploratorium for which she works — who are trying to draw from the best of the making and tinkering approach for low-income children.

If issues of social class are relevant to the Makers Movement, they are central to a current educational policy debate involving education and work: Should we as a society be encouraging all young people into postsecondary education or should we be encouraging some to enter after high school the world of work? And here I would like to bring back my plumber, Billy, for he could be the poster boy for one side of this debate.The last few decades have witnessed the rise of a “college for all” ethos in the United States, a belief in the economic and social virtues of encouraging increasing numbers of young people toward postsecondary education. On average, a college degree yields higher income over one’s working life, and this is especially true for people coming from poorer families. Recently, however, there has been push-back from some economists and policy analysts who argue, correctly, that half of the students who begin college never complete it, and can rack up significant debt in the process. Also there are people with bachelor’s and master’s degrees who are driving a cab or working at Starbucks. This is unfortunate, the argument goes, for there are good jobs available that require training and possibly an occupational certificate, but not necessarily a two-year — and certainly not a four-year — degree. These include so-called midlevel technical jobs in health care or manufacturing as well as skilled trades and certain service jobs. They pay well and can’t be outsourced. Billy has to come to your house to clear your drain.

Another reaction to this focus on a college degree comes from educators who emphasize the wide variability in students’ interests and aptitudes. Some students find little fulfillment in the traditional academic curriculum, no matter how well taught, but might thrive in a vocationally directed course of study. And there are social commentators who question the value of white-collar work that has gotten increasingly abstract and disembodied and call for a reinvigorated contact with the physical world — the kind of connection provided by the Makers Movement and by the crafts and skilled trades.

But how good an education can vocational education — now called career and technical education or CTE — provide? The advocates for CTE see it as a pathway to solid employment. Yet, while there certainly have been successful programs and dedicated shop teachers in the past, the sad fact is that over the history of VocEd, working-class kids have been disproportionately tracked into the vocational curriculum, and it has generally not provided a very good education or led to good jobs. Billy got his training through work, not school.

Beginning in the early 1990s, there has been a significant effort to reform vocational education, to beef up its academic content and to provide better pathways to both postsecondary education and to employment. High schools, for example, developed “career academies” whereby students could be introduced to an occupation (from the arts to health care) while taking academic courses that drew on occupational topics and materials. School politics and reforms are a complex affair, however; while career academies and other experiments were unfolding, other elements of career and technical education — the traditional shop classes particularly — were being cut. CTE has taken a huge hit over the past several decades, its suitability for our current economy and, no small matter, its expense questioned — it costs a lot to maintain state-of-the-art labs and workshops. Where CTE programs did survive, they often were reoriented toward health care, high-tech or, more recently, given a “green” focus.

But the reconsideration of college-for-all, the recession and government investment in workforce development have combined to produce a resurgence of CTE in some areas, particularly for jobs considered to be part of the new economy.

One popular model frequently in the news is a partnership whereby an industry teams up with a local community college to train students for high-demand jobs in that industry — specialized computer-assisted manufacturing, for example. These programs are understandably popular, for they are short term and provide a pathway to employment, a godsend in communities wracked by the recession. A concern is whether the training is narrow or broad in scope, providing knowledge and skill for people to move into other kinds of work if the specific job they trained for becomes obsolete.

This concern about a more comprehensive education is being widely discussed in CTE circles today: What does it mean to be educated in a rapidly changing work environment? Are we providing adequate knowledge and skill for students to continue learning, to have a future orientation to the world of work? The best CTE (or older VocEd) programs I’ve seen help students become more literate and numerate and teach processes and techniques in ways that develop broader habits of mind. An automotive technology program I visited recently had students learning about diesel, hybrid and compressed natural gas vehicles along with the ’98 Dodge — and the program emphasized problem solving, principles and concepts, understanding machines as systems. “The textbook gives you the mechanisms,” a student explains, “their function and their purpose. But our teacher, he gets us to see that when x fails, then y fails. Man, that’s a whole different story.” Another student, studying to be a bus mechanic, characterizes his program’s approach toward repair: “You’re like a doctor. You use all your senses, and you also ask the driver, what’d you hear? Feel? Smell? And you put that together.”It comes as no surprise, given the place of high-technology in the culture at large, that there is real excitement in CTE about the educational possibilities provided by the high-tech nexus of computers, engineering and design. This is similar to the excitement one finds in making and tinkering circles. I visited the lab in a design program at a local community college, and there amid various computers and computer-design equipment, robotics kits, laser cutters and 3-D printers were students working on projects, talking about design principles, aesthetics and marketing. This isn’t your father’s shop class.

The big question that will determine the future development of career and technical education will be whether we can truly bridge the hundred-year-old divide between the academic and vocational curriculum. This separation limits the ways that academic content can be brought to life through tasks and simulations drawn from the world of work, and it has diminished the considerable intellectual content of occupations. There has been a lot done to narrow this curricular gap, from career academies to the emphasizing in some programs of the intellectual content of work. And there are new approaches that affect CTE. Linked Learning advocates that all children get a uniform education in mathematics and English, arts and sciences, and only then branch off to a college or career oriented course of study. And as I mentioned, the advocates for making and tinkering in education see it as transcending this divide, for it blends hands-on play, creativity and learning in a range of subject areas. For Linked Learning or any revision of CTE to be truly effective, however, we will need to take the young people who pursue an occupational education seriously as thinkers and their engagement in work as an opportunity to explore topics typically found only in the academic curriculum, from aesthetics and ethics to history and politics.

Fortunately there are programs and schools that have this kind of engagement as their central mission. Big Picture Schools, a network of 50-plus schools across the country, is one such effort; High-Tech High, a Southern California network of 12 elementary, middle and high schools is another. Both of these organizations, in different ways, have created courses of study that blend occupational and academic learning from the ground up, are heavily driven by student projects more than a fixed curriculum, and recruit students from all income levels, with concentration on the less advantaged. I have sat in on a meeting of Big Picture principals, and in addition to being impressed with their creativity and zeal, I was also struck by just how hard their work is, trying to push against so many established ways of doing things and of thinking about ability and learning. But the payoffs are powerful, with strong rates of graduation and postsecondary study. And there is the intense fulfillment of watching your students develop into competent, thoughtful people. The founder of the other organization, High-Tech High, tells me this story. A visitor asks a ninth-grader about her homework, and she says she doesn’t have any. Surprised, the visitor then asks what she does at night, and she replies that she works on her projects.

Teachers pray for that kind of involvement.

The preceding was adapted from the new preface to “The Mind at Work,” a modern classic about education and labor.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.