The Hack: Reflections on a Nazi-Era Filmmaker

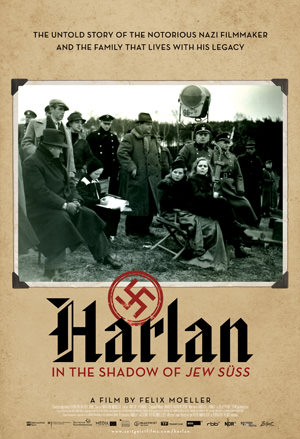

"Jud Süss" may be the most odious movie ever made And now we have a talking-heads documentary about it, “Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss,” the work of Felix Moeller, in which the children and grandchildren of the film’s director, Veit Harlan, are invited to comment on the patriarch’s noxious work Now there's a documentary about it that abounds in talk but fails to truly explore this 1940 product .

In 1940 a film called “Jud Süss” was released in Germany and the rest of Nazi-occupied Europe. It was a huge success—at one point it was playing in over 60 theaters in Berlin alone—and, by common consent, it has entered both film and cultural history as perhaps the most odious movie ever made.

Which may or may not be true. There are film historians who believe that the Germans produced, around the same time, even more vile anti-Semitic pictures. But “Jud Süss,” because of its popularity, has become the legend against which all other anti-Semitic cultural products are measured, even though it has basically not been seen by anyone except scholars and one particular ethnic group since 1945. But out of sight does not mean out of mind. There is scarcely a book about Nazi culture that does not include a still from the film, a documentary about Hitler’s Germany that does not contain a clip from it. And now we have a talking-heads documentary about it, “Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss,” the work of Felix Moeller, in which the children and grandchildren of the film’s director, Veit Harlan, are invited to comment on the patriarch’s noxious work.

The documentary is not very good. It is repetitive and one-note: Essentially family members compete among themselves in condemning Harlan and his work and in retailing anecdotes of their own shame at bearing his name and infamy, even now, 70 years after the picture was released. This has an unintended consequence, granting Harlan unearned stature as an artist while imbuing his story with a tragic dimension that is equally unjustified.

The facts about his case and his film—most of which are not alluded to in the documentary—are much more interesting than anything presented in the film: Harlan was, by all accounts, a loud, crude sometime actor who had drifted into directing in the silent picture era, where he found solid success, largely as the creator of romantic-historical dramas of a kind more appreciated in Germany than elsewhere. He appears to have been apolitical—he never joined the Nazi Party—and to have been roughly the equivalent of a Hollywood studio director of that era, a reliable purveyor of more or less risible movies, worthy of no more than historical interest and perhaps some nostalgic regard from those German pensioners who happened to catch his films in their impressionable years. If he had not made “Jud Süss” almost no one today would ever have heard of Viet Harlan.

That story had its roots in history. In 1732 a Jewish financier called Josef Süss Oppenheimer made his way to Württemberg, Germany, where he became financial adviser to its genial and profligate duke. Eventually, he bankrupted the duchy and was tried and executed for his machinations, which brought economic ruin to the state. There is no question that anti-Semitism was a factor in his demise, and his tale, heavily encrusted with myth, became a minor, undying footnote in German mythology. Interest in his story was revived in 1925 when Lion Feuchtwanger, a popular and well-regarded novelist of the time, wrote a best-selling book that was quite sympathetic to Oppenheimer, going so far as to posit that Christian blood flowed in his veins, a fact that might have saved him from execution, had he chosen to admit it. This version of the story was, in fact, made into a movie in England in 1932 with the “satanic, brilliant” Conrad Veidt (later, immortally, Col. Strasser in “Casablanca”) as the central character.

Like most mythic tales, this obviously was one that could be spun in any direction its current teller chose, a fact that was not lost on another satanic, brilliant and entirely perverse figure, Dr. Josef Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister and, by the late ’30s, de facto head of the German film industry. He repeatedly ran the English version of the story and even contemplated buying the film, to re-edit and rerelease it. Instead, of course, he decided on a remake, recruiting Harlan as his director. The latter appears not to have been notably anti-Semitic, and if even a portion of his postwar testimony is to be believed—he was twice subjected to de-Nazification hearings and twice cleared of collaboration with the regime—he did attempt to squirm out of the film, even offering (he claimed) to serve as a private in the army in exchange for evading the job. The same reluctance was displayed by almost all the actors considered for the film’s cast. They offered some later testimony regarding Harlan’s cynical advice about dissuading Goebbels from casting them. Above all, he suggested, don’t look down; the man had a club foot and was understandably sensitive about the defect.

The picture proceeded smoothly in production—with the sensational immediate results we’ve already observed. Those critics who have seen it mostly deem it a crude and vulgar piece of work, though reports that “Jud Süss” actually cost lives on a few occasions when it was riotously received outside Germany were never satisfactorily verified.

These are among the many points a worthwhile documentary on this fascinating topic needs to make. But the excessive concentration on Harlan’s progeny, all of whom genuinely loathe “Jud Süss,” skews the story. Implicitly, they want us to see him as some kind of a mysterious and tragic figure, a major artist betrayed by his own flaws. Better for us to see him as a possibly great man brought low than as a relatively minor functionary of a totalitarian state, getting along by going along. Better for him to be an exemplary figure in a dark drama than a curious footnote in the horrifying history of National Socialism.A small dose of reality enters the film with the appearances of Christiane Kubrick and Jan Harlan. They are the niece and nephew of Harlan and, respectively, the widow and the long-time production associate of the great American director. She met Kubrick while working for him as an actress in “Paths of Glory” and, in due course, she introduced Kubrick, a Jew, to her uncle. She recalls her husband fortifying himself with a tall glass of vodka before the meeting. More important, she remembers him pondering the older man’s career in highly personal terms, wondering what he might have done had he been in Harlan’s position in Nazi Germany. Kubrick had served time in Hollywood, he had seen plenty of directors compromise their best impulses in order to sustain their careers. Above all, he could understand what a short, careless step it might have been for Harlan to do a distasteful job for Goebbels. He seems to have thought it was a little like doing something unworthy, but easily forgotten, for Louis B. Mayer. He was also thinking “there but for the grace of God. …” According to Mrs. Kubrick, he made extensive notes for a film he considered making about Harlan, though nothing concrete came of this interest.

Putting the point simply, Stanley Kubrick knew—from observation, never from practice—what it was to be a hack. Central to that identity, I think, is the sense that no large consequences ever flow from any particular artistic enterprise. The idea was just to keep moving from one forgettable project to the next, earning a nice living, making a comfortable life. Whatever pretenses about his work that a hack may offer the public, in the deepest part of his soul he thinks no one is paying much attention to him, that he can pretty much get away with anything.

Up to a point, this proved to be the case with Veit Harlan. He continued to direct throughout the Nazi years, most notably with “Kolberg,” a historical military spectacle, that diverted resources the Nazis could well have deployed elsewhere in the waning years of the war (Goebbels found his rough cut “defeatist”). At his de-Nazification hearings Harlan presented himself as an innocent victim of Nazism, even claiming to have written and shot an exculpatory ending for “Jud Süss,” which, naturally, Goebbels rejected.

We don’t know that for certain. What common sense tells us is that a man as well connected as Harlan was had to know in 1940 something like the full meaning of Nazism. What we do know is that by 1950 Harlan was directing again; he made no less than nine movies in the following 12 years, perhaps not knowing that “Jud Süss” was then—and later—circulating widely in the Middle East, continuing to do its evil work among Muslim audiences at least as receptive to its message as the Nazis had been.

It’s well and good, if useless, for Harlan family members to decry their patriarch’s sins, for which, obviously, they bear no responsibility and thus no guilt. But in narrowly focusing on them, Moeller has blown off two opportunities—to fully tell a fascinating story and, more important, to reflect on the consequences of the hack mentality. It is more than possible that amorality—“just doing my job”—is just as loathsome as immorality—“I really like doing my job.” In any case, it remains the central conundrum of Nazism, entirely unexplored in this documentary.

Richard Schickel, whose celebrated and prolific career spans 50 years, has been the film critic for Time and Life magazines, has written more than 20 books and has produced, written and directed numerous documentaries.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.