‘The Good Fight’ Shows Us a Better Reality on TV

CBS All Access' legal dramedy plays like more of a fantasy in the current climate, but it’s just the show we need right now. From left: Audra McDonald gets into character as Liz Reddick-Lawrence; Christine Baranski as Diane Lockhart; Nyambi Nyambi as Jay Dipersia in CBS All Access' series "The Good Fight." (Elizabeth Fisher / CBS All Access ©2017 CBS Interactive, Inc.)

From left: Audra McDonald gets into character as Liz Reddick-Lawrence; Christine Baranski as Diane Lockhart; Nyambi Nyambi as Jay Dipersia in CBS All Access' series "The Good Fight." (Elizabeth Fisher / CBS All Access ©2017 CBS Interactive, Inc.)

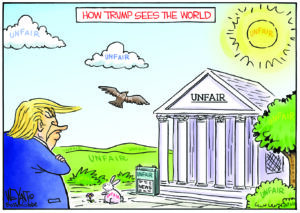

Angry, uncivil tweets pass for leadership and news. Billionaire lawmakers yawn at gaping inequality. Administration officials lie incessantly, as if for sport.

Meanwhile, the makers of CBS’ terrific tragicomic legal show “The Good Fight” pack their plots to the breaking point, with storylines involving issues ranging from immigration to impeachment, police brutality to states’ rights, everyday infidelity to #MeToo infractions, hacker/bot abuses to dubious legal ethics.

But our nation’s breaking point is largely what this show explores. The still-life success symbols and caricatured leaders in its title sequence warn of a possible explosion in every episode.

There’s an absurdist whiff to the ensuing bedlam, and the writers help their characters escape tight story corners a bit too often, à la deus ex machina. Nevertheless, the show presents an apt response to the roiling ghost-of-Roger-Ailes world and a cunning cross-examination of our once-and-future democracy.

Beyond integrating unpresidential performance politics with other callous actions of America’s most powerful classes, this thrumming series delivers something significant, unique and long overdue in television: a racially integrated, gender-balanced dramatic landscape. It has little in common with the world that most American professionals have had the opportunity to take part in during their lifetimes—but much to suggest about our potential for cooperative harmony.

The show’s majority African-American law firm, Reddick, Boseman and Lockhart, is no nirvana. But its creators have imagined a microcosm that is pragmatic and mostly plausible as well as intelligent, competitive and committed to justice. Most importantly, it demonstrates how and why to not give up any fight after a first-round loss.

Set in Chicago, like its soapier precursor “The Good Wife,” the series’ location is demographically believable, if not quite accurate. (Chicago is roughly a third black, a third white and a third Hispanic. Hispanic representation on the show is minimal.) It’s also a timely setting, especially regarding issues involving the law, its enforcement, and race. While not central to the series, the persistent, unsolved status of these problems is integral to the show’s weave of critical American themes. It is established early on, for example, that the firm largely made its name winning police misconduct cases.

What sets “The Good Fight” apart, and ahead of many headline-oriented shows, is that creators Robert King, Michelle King and Phil Alden Robinson have invented an arena that is aspirational in its makeup and its mission. (Aspirational for anyone who roots for equality, democracy and the ideal of forming a more perfect union.) And although the characters do not pretend colorblindness, they are written and played as if they work in an essentially ethical meritocracy, in which each stands on solid, supported ground—at least when within the interior boundaries of the firm’s offices.

Inside, they strategize about how to level the landscape for their clients and ways to win compensation for victims of bias and lawbreaking of all kinds. Outside its glass walls, the firm’s black team members again become susceptible to the perils of the unjust, unequal society in which they, and we, live.

This hyper-textured imaginarium plays out as a kind of about-time, duh, cultural moment. Because, of course, life in these Unites States could be less rancorous, as well as more humane and productive, if we’d stop denying history and welcome the strengths and advantages that diverse experiences bring to almost any situation. But as a response to “trumpy” times, the series is a weekly repudiation of the unleashed racial animosity that is arguably a foundation on which the president built his campaign and won, and which has become stridently pervasive since the election.

The opposite of a cynical dream team, the show’s legal firm remains a dream thus far. (Hollywood should take notes, because its culture machine constructs the mirror through which much of America sees itself. More often than not, it dreams of winning awards rather than equality.)

Considering the dark and devious forces with which the fictional firm wrangles, the show’s tone is surprisingly buoyant, sometimes madcap and often very funny. Not since the film “Bulworth” has so much humor been wrought from dramatizing racial politics. The filmmakers seem committed to levity, mining laughs in inventive and timeless ways, from onomatopoeic character names to artfully timed expletives.

And is using magic mushrooms the way to manage being sentient in these trying times? The writers slowly unwind this joke into a serious question, through Diane Lockhart’s professional, political, and private dilemmas. As Diane, whom “The Good Wife” watchers will remember, Christine Baranski melds smoothly with the talented acting ensemble and gets just enough screen time to warrant her top billing. She appears to be infused with bursts of energy as she rises from the dust of her previous stuffier life, microdosing mushrooms, re-evaluating her choices and searching for her own strength as she watches the country deteriorate. Seeing her resurgence, one argument at a time with a steely level gaze—as when she refutes weaselly Trump appointee Mike Kresteva’s (Matthew Perry) lies—is a thrill. For her, fighting the good fight becomes invigorating and transformative.

The series’ production values are stellar, and watching it is like enjoying a dessert that’s also nutritious. But the costume design is in a cinematic class all its own, boldly elevating theme, conflict and character. The colors, combos and textures are often wild and inspired, always reflective of subtext and personality. For the firm’s leader, Adrian Boseman, and its top investigator, Jay Dipersia (Delroy Lindo and Nyambi Nyambi, perfectly cast), the clothing choices align with their converging and diverging spirits and styles. Adrian dons elegant three-piece suits of all shades, punctuated with joyful tropical colors; Jay stays subtle in current earth-toned styles. Both are fair-minded and far-thinking, committed to the team and the fight.

The female characters’ strengths and challenges correlate to all aspects of wardrobe. Indomitable Lucca Quinn (Cush Jumbo) speeds between legal crises and colleague rescues in mixed patterns, miniskirts and flats, sure of her brilliance. And crazy-like-a-fox Elspeth Tascioni (Carrie Preston) frequently throws the seriousness of the moment off balance to compliment friend and foe alike—on earrings, jackets, lipstick, you name it—each time with a psychedelic zest in her voice to match her embroidered blazers.

A refreshing detail is that the unbalancing four- and five-inch heels seen so often on today’s screens are less visible in “The Good Fight.” The woman most often shod in this form of self-torture is the greenest of the group, Maia (Rose Leslie) who, luckily, is also Diane’s goddaughter.

Diane appears less upscale-matron, more devil-may-care maven in this spinoff, as when she wears a knockout black-and-blue plaid jacket that’s haphazardly patched, much like her new life. Attorney Barbara Kolstadt (Erica Tazel) assumes the role of matron, in wardrobe and carriage, and rarely misses a chance to remind Diane of her place, despite Adrian’s admonitions. (Their competitive conflicts present opportunities to look closely at power and how it’s maneuvered.)

So, three tips of a fabulous hat to lead costume designer Daniel Lawson and his team, who have designed, found or retro-engineered a fiery, funky visual pallet of textiles, patterns and shades that correlate to the range of richness our multi-colored, diverse America offers. The legal defenders they dress don’t always win, but they’re committed, wicked smart and ever resourceful.

By the season two finale, the story lines have careened and twisted into a dangerous mess of chaos and cruelty, just like America today. Even a new baby, usually symbolic of hope in narrative fiction, is born to Lucca in a storm of crazy cursing, and his homecoming leaves us off-kilter because his parents just can’t come together right now.

“The Good Fight” may not be transformative, but it’s invigorating and inspiring entertainment for our unnaturally disastrous times.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.