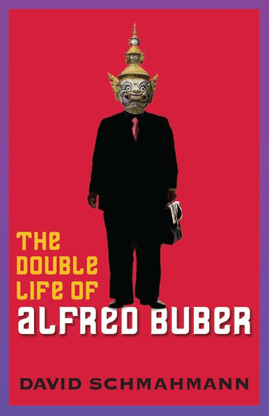

‘The Double Life of Alfred Buber’

In David Schmahmann's new novel, Alfred Buber is a respected man with a secret. Telling his boss and colleagues that he's going to Paris, he regularly travels instead to Southeast Asia to go whoring in the squalid back alleys. And then on one of his trips to Bangkok, he falls in love.An excerpt from David Schmahmann's new novel, about a john who falls in love with an Asian prostitute.

There is a Madonna video playing on the television and one of the girls asks if I like the music. I have fastened my clothes. Nok has disappeared into the back room presumably to clean herself. I am suddenly as weary as I have ever been.

“Yes,” I say. “I like.”

“I like too,” she says, and then, without further preliminaries, she pulls me up from the bench and begins to dance with me and then we are dancing quite close together, her head on my shoulder, my arm around her waist. I close my eyes and suddenly I find myself overwhelmed by a sense of sadness and loss, thinking of Rhodesia and my father’s old Morris car, of Henshaw and of my almost completed house, of Rebecca sprawled across my bed, of the great distances still to travel before I am home. I think of my hotel room with a suitcase lying opened on the bed, of white sheets, dark shining hair, polite nods, of the years of my life that are left, of my parents and their archaic beliefs, of their scarcely genteel poverty, of the poverty of these girls. For some inexplicable reason I sense that my eyes have filled with tears, that I am holding this girl far too tightly even as she says nothing in protest.

The music finishes and for a moment I do not release her and we stand together in the middle of the floor. As I take my arm from her waist she looks up at me and then touches my shoulder.

“American man okay?“ she asks.

“Okay,” I answer.

These people have seen everything, I am sure. A displaced and weepy foreigner cannot be the most unexpected event in the Star of Love Bar. I see that Nok has returned from the back room. She has put on her red robe, fastened it now in the front as if there is some newfound need for virtue, a place here for chastity.

She has roped her hair back, is rubbing cream onto her face with small flicks of her fingers.

“You okay?” she asks.

Her eyes are bright and earnest. She is carrying her book.

“What is that book?” I ask, and reach for it.

She offers it to me with both hands. It is the kind of booklet one might give a child to teach it its first few words. There is a picture of a bus and the word, “bus,” a car, a toothbrush, a house.

“How good is your English?” I ask and she says: “Only a little.”

“This isn’t the best way to do it,” I say. “There’s got to be something better.”

She shrugs.

“Friend give this me,” she says.

I have noticed a bookstore nearby, stepped in earlier for a few moments of respite.

“I’ll get you something better,” I say, and Nok, as unsure what to make of the offer as I am of the reasons I am making it, says only, uncertainly, “Okay.”

“Do you want to come with me?’ I ask, and she says, “If I leave, you must pay the bar fine. Better I wait for you.”

Mercy. Buber the educator scurries from the bar on his mission to spread Christianity to those who have recently orally serviced him. As the door closes I hear a heated discussion break out, shrill voices, can only guess at its content. I find the bookstore, its English as a Second Language section, flip through its selection. I don’t know what I’m looking for. ESL: Elementary Job Interview Skills. Now what skills would those be for this time and place? I have a plane to catch, a taxi ordered, a blow job girl waiting for upliftment. I make my selection and walk back briskly.

As I approach, the girls on the stools outside the bar come to life. One of them leans over and presses the buzzer and the door opens. Inside I find that a group of men has arrived and is prospecting. One of them is talking to Nok, one hand on her shoulder, another on her stomach. He is stroking but also probing. She stands quite still. I seethe.

“Nok?” I say.

She puts her hand on the man’s arm, moves it away, asks him to excuse her.

“Many other girl,” she says and then, pointing to me, adds, “my boyflen.”

Oh does that show of loyalty not move the chemicals about. I hand her the book and she leads me to the back of the bar. There are several folding chairs and she sits on one, gestures for me to sit beside her. She goes through the book carefully, one page at a time.

“I think this one better,” she says after a while. “I want … I wish … to English.”

“To speak English,” I correct.

“To speak English,” she says.

“And to get a good job,” I add. “A clean job.”

“Clean?” she says with difficulty, and we flip together — she turns some pages, I others — to the back of the book. We find the word in the glossary.

“Oh,” she says softly and then she looks back down.

“Yes. A clean job.”

I look at my watch, know that I have to leave. I reach for my wallet, open it, extract the remainder of my currency. She looks at the money, a lot by any measure, puts her hand on mine, presses it away.

“It okay,” she says. “Not necessary.”

I look across at her, at her upturned face, her slender hand on my arm.

“I’m sorry,” I say, “for that,” and gesture at my lap.

Her smile drops, her face clouds.

“No sorry,” she says. “My job. Only job.”

“You’re lovely,” I say, but it is clear she does not understand. She stands, looks at something in the room, at the row of liquor bottles against the wall, the television set with its karaoke tape.

“I could marry someone like you,” I say on impulse, my hand going now from my heart to her breast.

She smiles, looks at me as if what I have suggested is not as preposterous as it obviously is, has no weight but is not entirely a joke.

“Okay,” she says. “I wait you.”

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.