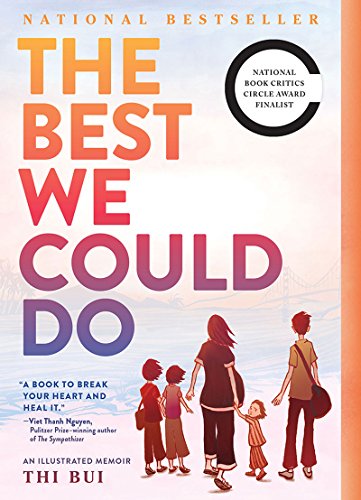

The Best We Could Do

I thought graphic novels were kid stuff -- and there is no better book to prove me wrong than this turbulent memoir of a Vietnamese family.

“The Best We Could Do” A book by Thi Bui Reviewed by Janice Raymond

To see long excerpts from “The Best We Could Do” at Google Books, click here.

When asked to write a review of Thi Bui’s book, “The Best We Could Do,” I hesitated. I had never read a graphic novel, much less reviewed one. Of course, as a kid I had read many comic books, but had never considered these graphic novels.

In pursuing information about the graphic novel, I learned there is much debate about what to call any graphic with text, encapsulated in book form. Is it a genre or format, what some would call a medium? Is it sequential art? Is it fiction, memoir, or something else? Many assert that the term “graphic novel” includes nonfiction as well as fiction. Or is it simply a book-length comic?

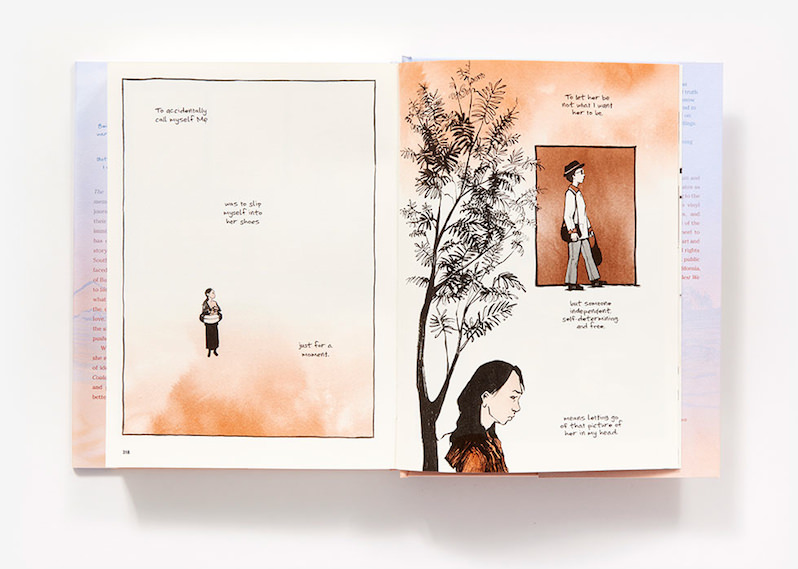

I had heard about “March,” the graphic trilogy of young civil rights activist John Lewis, which recently won the National Book Award for young children’s literature. But this was part of my hesitation. Graphic novels were kid stuff, not serious writing. I was wrong, and there is no better book than “The Best We Could Do” to prove how faulty was my impression. This migration memoir of a Vietnamese family is illustrated in what I would call a visual prose that befits the ebb and flow of the author’s turbulent and moving journey. As one commentator said of this genre, “There are numerous treasures lurking in the graphics.”

“The Best We Can Do” is much more than the personal chronicle of a family ravaged by war and forced migration. It is the story of a family seeking refuge whose experiences reflect the larger social and political contexts of the “fog of war,” nationalism, communism, refugee camps, and multiple relocations only to end in the United States. It is also a moving quest narrative to locate the author’s own place in the history of her family and in the history of a country called Vietnam.

The book begins in the present, but the past is always present. There are two migrations — the journey from Vietnam via Malaysia to the United States; and the family’s U.S. relocations from first landing in the Midwest and then resettling from East to West coasts.

The memoir begins in 2005 when we observe Thi giving birth to her son in a New York City hospital. It is not an easy labor and delivery. Her mother, Má, comes from California to be with her but cannot bear to be in the same room, as Thi endures pain and anguish. In absenting herself from the labor room, Má seems to conjure up her own difficult birthing of Thi’s brother in a refugee camp in Malaysia. The whole process of labor and delivery serves as a stand-in for the arduous journey illustrated in the rest of the book.

One of my favorite graphics comes in the beginning of the memoir where Thi traces the family’s “journey in reverse, through the war, seeking an origin story that will set everything right.” She draws images of desperation and escape. The wreckage of a country, the boat that carries them from Vietnam to Malaysia and the immense waves, bring her reflections to life.

In addition to a mother (Má) and father (Bô), Thi has three siblings: her older sisters Lan and Bích and a younger brother, Tân, who make the journey. Two sisters died before leaving the country, and they take the form of phantoms in the family pantheon.

The family saga begins with colonial wars — those of the French, Japanese, Chinese, and French redux occupations in what was then called Indochina. The violence of these years mirrors the violence in the personal lives of Thi’s parents. Thi shows us what Bô endured as a little boy in Ha’i Phòng, the northernmost port in Vietnam 200 kilometers from the Chinese border. Bô’s father had joined the revolutionary Viêt Minh, but his ideals don’t lodge in the domestic context. Bô and his mother suffer from the violence of Bô’s father. The violence comes full circle when Bô, the terrified boy, grows to become a terrorizer of his own wife and children.

Feminists of the 1960s generated the refrain, “The personal is political.” This is an apt description of Thi’s effort throughout the book as she sketches her family’s history: of the famine years when all the food grown was requisitioned by the clashing French and Japanese armies; the return of the French colonizers; the 1945 victory of Hô Chí Minh; and the partitioning of Vietnam in 1954. Thi wonders had the North and South consented to unify before the French returned after World War II, how different her life might have been.

But the political is also personal, and Thi inverts the refrain by always bringing history and politics home. Thi’s mother, Má, had been born in Cambodia to a professional family. Má’s father worked as an engineer for the French and, later, as the chief of public works for the government of South Vietnam. The family enjoyed the services of cooks, chauffeurs and gardeners. Youngest of five children, Má was an excellent student educated in French schools in Cambodia and Vietnam. Má’s mother, however, beat her children.

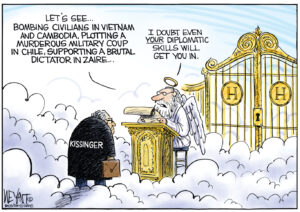

The American war on Vietnam, which begins in the 1960s, features prominently in the book. American planes carpet-bombed a richly agricultural country with napalm and defoliants, the worst among them Agent Orange. The United States dropped more bombs on Vietnam than were dropped in all its previous wars combined, and unremittingly sprayed Agent Orange across the war zones. I had been to Vietnam in 2014, part of a project to meet and raise support for second and third generation children who had been profoundly damaged by Agent Orange. My personal interest in visiting the country was catalyzed by having a nephew and grandnephew whose disabilities, in all likelihood, are the results of my brother’s exposure to Agent Orange at the beginning of the American war.

In every war, there are contradictions. Thi draws a landscape of contradictions in the history of Vietnam and in the ways in which family members view the conflicts. Bô has little identification with the Hô Chí Minh regime that “…had to kill all those people who were friends of the French. … They called these SACRIFICES.” Thi makes visible cities that become police states, villagers who turn on one another, and the many who are labeled enemies of the state, rounded up and treated as criminals — some to be killed, some disappeared, and others to be reformed.

However, the contradictions in her father’s stories have troubled Thi for a long time, though she doesn’t specify what they are. Here, the reader senses a disjunction between the image and the text, which don’t quite match up. Thi recognizes the oversimplifications of the war in the American media, and seeks to illustrate, in dueling stereotypes, who gets designated the good guys and bad guys:

Good Guys — “the American soldiers and the American version of the war.”

Bad Guys — “the Viêt Công (communist front in the South)…Very hard to see.”

The South Vietnamese — “The bar girls and ‘hookers,’ the corrupt leaders, the Papa-sans, the kids looking for handouts, and the small effete men” overshadowed by the tall American soldier.

The author acknowledges there is no single narrative of the wars that Vietnam has experienced throughout its history. The story is in its people, in those who stayed and those who left.

To young generations, both in Vietnam and the United States, the American war and its consequences are a faraway tale. One of the many things that make these events relevant today is the occurrence of the largest migration of people in history. This migration flow has become a crisis in almost every part of the world, both in countries from which people are fleeing and in the countries to which they emigrate. “The Best We Could Do” is akin to this contemporary plight of refugees, viewed through the lens of a single family and presented in visual prose. It has all the hallmarks of a book that will be regarded as a pioneer in both form and content.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.