The Abu Ghraib Photos You Haven’t Seen

“Riley and his story Me and my outrage You and us” is a piece of art and a historical document It’s a war story and a meditation on memory as well as a rumination on its absence“Riley and his story” is art and history.

I’ve spent a big chunk of the last decade immersed in people’s wartime memories. I’ve traveled across the globe to interview survivors about them — soldiers, guerrillas, civilians. I’ve read countless memoirs, reporters’ accounts and historians’ works on the subject of war. Along the way, I’ve also learned a lot about memory, specifically how people remember and forget certain incidents.

I’ve spoken to not a few veterans who’ve committed atrocities — including men who readily admitted the brutal deeds they had carried out as teenagers or 20-somethings. But sometimes I knew about a specific horrific act they witnessed or probably carried out and it seemingly was news to them. “I don’t recall it, but I can believe it” is a standard response. Or there was the officer who reportedly went around rounding up men to kill a group of women and children. “I guess I’ve wiped Vietnam and all that out of my mind. I don’t remember shooting anyone or ordering anyone to shoot,” he said when confronted. But he didn’t dispute that the massacre had occurred, saying “I don’t doubt it, but I don’t remember.”

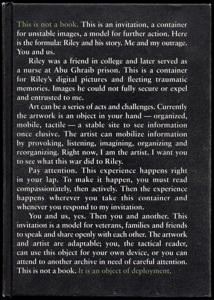

Riley Sharbonno didn’t round up people. He didn’t carry out any massacres and didn’t witness any. But Sharbonno did go to war. And he did return with memories that were mixed up, messy or missing. Monica Haller helped him to put them back together in a fascinating photo book — a term she eschews, instead calling the project “an object of deployment.”

A thick tome of more than 470 pages, “Riley and his story. Me and my outrage. You and us.” is a piece of art and a historical document. It’s a war story and a meditation on memory as well as a rumination on its absence. [To see excerpts, click here and then click on “Download a PDF” at the bottom of the Web page that comes up.]

About to go into its second printing, “Riley and his story” offers readers something unique and haunting: a look through the eyes of a veteran who served at perhaps the most notorious locale of the Iraq War, one that historians will catalog alongside My Lai, No Gun Ri, Samar and Sand Creek — notable sites of past American atrocities. Sharbonno, a nurse at the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 and 2005, offers us a tour of his tour of duty through some of the 1,000 photographs he took. But these aren’t the photos of Abu Ghraib that we’ve seen before. There are no detainees on leashes or nude human pyramids or unmuzzled dogs menacing naked defenseless men. Still, this young veteran’s pictures offer a clear vision of the awfulness that is war.

“Many events during my time in Iraq were too complex, too horrific, or beyond my understanding. There were simply too many things I witnessed there on a given day to process, so I stored them as photos to figure out later,” writes Sharbonno, who provides snippets of text — taken from conversations with Haller over a period of three years — that narrate his photos throughout the book.

Right away we’re hit with a two-page spread. Thick fingers, clad in white surgical gloves, holding a shard of metal shrapnel still coated with human viscera. Then we’re off with Sharbonno on a convoy, a medical supply run between Baghdad and another place whose name is destined for infamy: Fallujah. The central feature of these photos, and other out-the-window shots from helicopters later in the book, is not the Iraqi landscape, not fields of brown and green, or waterways with floating garbage, or the trash dump with grazing cows in it: It’s the gun barrel in the foreground. And it reveals so much that so many books on the Iraq War fail to convey.

As a capstone to the sequence, Sharbonno explains the story behind one key photo, an instance in which he spotted a figure in a dump truck with what appears to be a machine gun mounted on it; a figure neither he nor any of the others in his vehicle were able to discern as either friend or foe. The Americans pointed their weapons at the mystery man, but none pulled a trigger. Instead, Sharbonno took his picture. I’m certain the nameless, faceless figure is grateful for it, but it only drives home the fact that this is the essence of the American project in Iraq — a machine gun perpetually pointed out the window, automatically trained on anyone who happens to be there.

There are also blank spaces in the book. Pages without pictures or text. Pages with only text. Pages that offer clues about what might be missing. “Even today, there is so much — huge chunks — that I can’t figure out if the events really happened or not,” Sharbonno writes. There are some things that never appear in photos but are so vivid that we can’t help seeing them. We’re reminded that before it was a notorious site for American atrocities, Abu Ghraib was a notorious site for Saddam Hussein’s atrocities. The young veteran writes:

At Abu Ghraib everywhere we dug — and we dug four or five times — everywhere we dug we found human remains. I dug once to try and build a garden, we dug to build a shower, which ended up being the morgue. We dug to put in fences, to put cables down. … Every time we dug, we found human remains. Every time. The prison is built on a mound of human remains. It’s just disgusting.

And sometimes we’re just left wondering. A large part of the book consists of pictures from one mass-casualty situation. Bloody shots. Gory shots. Shots of medical professionals moving with rapidity. “ ‘Holy shit. Is this really happening?’ So I just snapped pictures,” he writes in the midst of the morbid montage. Picture after picture. Pictures of parts of humans turned into chop meat. Unidentifiable bits of bodies torn open. Why is a nurse taking pictures through all of this? we’re left to wonder. Why, at one point, does Sharbonno even pick up someone else’s camera and start taking pictures with it? Why isn’t he doing something medical? If the emergency room tent is filled to capacity with staff, why is he there potentially getting in the way? And if he isn’t in the way, why isn’t he lending a hand? But then, if we look closely, we notice Sharbonno is apparently in some of the photos. (We can tell by his name tape on the back pocket of his pants.) So he was apparently lending a hand. Then who took these photos? Maybe someday Sharbonno will sort all of this out for us, but in this book he doesn’t. It’s another blank spot, but what we can be sure of is that if he hadn’t documented the mass-casualty event, then it would be one big blank. We’d probably never know what it was like to be inside that tent and see the things Sharbonno saw, so we’re lucky he was playing photographer and not nurse for at least part of the time. We’re luckier still that Haller provided a means to get those pictures into our hands.

In addition to grisly, mundane and inexplicable photos, sometimes there’s a repetitive photo, one that seemingly stands in for missing images. Over and over we see a shot of weapons laid out in precise formation alongside neatly stacked ammunition. Most belonged to Marines killed on an operation not far from Abu Ghraib and their fellow Marines who stood guard over their bodies, while a few weapons were taken from Iraqis who killed those Americans. After we’ve gotten through looking at Iraqi bodies that have been turned inside out — gruesome shots of wounded, dying and dead detainees — we repeatedly see this tasteful photo of weapons that seem to stand in for dead Marines. It wasn’t that Sharbonno didn’t have access and opportunity to take pictures of the dead Marines — he covered their body bags with ice all through the night — but for whatever reason he didn’t. Why not? We can speculate, but in the end we’re left to wonder why their bodies remain out of sight when so many Iraqis’ bodies don’t. These questions lurk throughout the book, and far from being a shortcoming, they are what gives the book its ultimate power. Countless questions about the Iraq War still remain to be asked, let alone answered. Haller and Sharbonno’s book helps to give voice to so many of them.

“These aren’t the photos we’re likely to find in grandma’s photo album 50 years from now. But it would be nice if they could just sit somewhere like that,” Sharbonno writes in the latter part of the book and then repeats it almost verbatim closer to the end. The sentence clicked for me on a lot of levels. In recent years, some Vietnam veterans have gone out to the backyard to burn the photo album or the shoebox of images that they don’t want their kids to find after they die — pictures of mutilated bodies and severed heads and unit members clowning with corpses. The men in these now fading photos look much like the modern-day U.S. soldiers mistreating Afghan corpses in the recently released “Kill Team” images.

Some Vietnam-era snapshots are turning to ash, but that won’t be the case for digital photos sent and shared and copied in ways that were impossible a few decades ago. “Riley and his story” contains very different types of photos than those of the Kill Team or the Abu Ghraib torturers or the more generic war porn that circulates online, but it’s just as integral to understanding “the awful stuff,” as Sharbonno puts it, namely the stuff of war itself.

Since creating “Riley and his story. Me and my outrage. You and us.,” Monica Haller has gone on to collaborate with many other veterans, survivors, victims and perpetrators of war. The results, many other “objects of deployment,” however, have not yet been published. But one hopes they will be. Soon. And in great quantity. Especially valuable will be projects with noncombatants — the population that knows the most about and suffers the most because of modern war; people who lost friends and family members, people who were physically and psychologically wounded, people who were made homeless and hopeless, people who were made refugees, people who already had hard lives before war arrived on their doorstep. These “objects of deployment” will offer an important means for Americans to begin to understand the true nature of their wars. And we need them now more than ever.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.