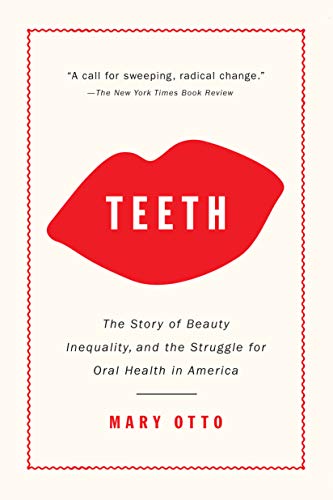

Teeth

A muckraking new book exposes the hidden reality of oral disease -- a stepchild in the health care debate and likely the largest pre-existing condition of all -- in the United States. New Press

New Press

“Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America” A book by Mary Otto

I have often felt that I’ve spent half my life in a dental chair. After three implants, two bridges, perhaps 10 root canals, countless fillings, numerous crowns and one especially painful gum surgery, I am a beleaguered dental veteran. My dental expenses over the decades have been huge. But I am especially cognizant of my social class privilege: I have dental insurance that, while hardly adequate, has covered some portion of my expenses. I can cover the rest myself because I have been fortunate to earn a decent living as a university professor for a long time.

But millions of marginalized Americans can scarcely imagine such dental care. Many have never had any dental care in their entire lives. If and when they do manage to see a dentist, the result is often that their throbbing teeth are extracted, alleviating the short-term pain but causing long-term problems. Communities of color and poor whites suffer the most, with a silent epidemic of tooth and gum disease. The consequences are horrific: severe, persistent and often intractable pain; diminished job prospects; acute embarrassment; major interruptions in learning for children with recurring toothaches; and poor nutrition, respiratory infections, diabetes, heart disease and, in extreme circumstances, death.

Almost none of this is on the national agenda, even during the current debates over the Affordable Care Act and the heartless attempt of the Trump administration to replace it with a scheme that will leave millions without coverage at all. Dental care is, at best, a stepchild in the conversations about health care needs and coverage. It is likely the largest pre-existing condition of all, yet privileged Americans remain largely indifferent to the oral suffering of their poorer fellow citizens.

To see long excerpts from “Teeth” at Google Books, click here.

Meanwhile, many affluent Americans, in the spirit of Thorstein Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption, spend thousands of dollars on various procedures of cosmetic dentistry, in their perennial quest to appear youthful, vibrant and attractive. Thousands of dentists, in fact, devote much or even all of their private practices to these procedures; some attend lavish seminars that show them how to market expensive procedures to their affluent patient populations. Journalist Mary Otto, in her muckraking new book “Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America,” addresses and critiques this dubious reality in depth throughout her volume.

Even more powerfully, she exposes the devastating consequences of ignoring dental health care in America. Her engaging yet disconcerting effort chronicles the hidden reality of oral disease in the United States. It traces the development of dentistry and dental education in the U.S., condemns the opposition of the organized dental profession to alternative, lower-cost approaches to dental care, and, above all, reveals the horrific human cost of oral neglect.

Of all the elements in this powerful work of investigative journalism, the winner of the Studs and Ida Terkel Prize, the most compelling is the tragic drama of people who suffer serious illness or worse from their untreated dental disease. The tragedy of Deamonte Driver, a 12-year-old African-American boy from Prince George’s County, Maryland, is the most poignant story of the entire book. Young Deamonte died following complications from a tooth abscess after his mother failed to find a dentist who would accept Medicaid to treat his toothache—a common occurrence in this country. After she took him to an emergency room, he received medicine for the abscess and he was sent home. But his condition worsened and he returned to the hospital. Doctors found that the bacteria had spread to his brain. Two surgeries and eight weeks of treatment failed and Deamonte died.

This is a moral abomination—yet another reminder of how American “health care” falls far below the standard for any civilized society. A simple visit to a dentist would have saved Deamonte’s life. Otto details others whose lives were lost because they had no access to basic dental treatment. As she reveals, “[d]ental visits to emergency departments nearly doubled between 2000 and 2010.” These visits involved tooth decay, oral lesions, abscesses, gum infections, and several other dental disorders and problems. Distressingly but not surprisingly, these patients rarely received any actual dental care, but merely prescription medications like painkillers and antibiotics. The author reports that during that time period, 101 patients died in emergency rooms. The financial cost, of course, was outrageously greater than what routine preventive dental care would have been if such care had been available to these unfortunate women, men and children.

A health care system that provides care for all, including dental care, would prevent all of this needless pain and suffering, and, ironically, save billions of dollars of taxpayer money. “Teeth” addresses this problem in multifaceted fashion. A key issue is the way that the American health care system separates the mouth from the rest of the human body, a view rooted in the separate development of medical and dental education that the author documents effectively.

This absurd view pervades the history of dental education and training in the United States. Dental schools, to be sure, reflect extremely high levels of scientific knowledge and they promote impressive levels of technical skills among their graduates. But this separation leads inevitably to a model of dental care delivery that works to the disadvantage of millions of less privileged Americans.

Dentists are largely independent of the medical profession and are rarely attached to hospitals and medical centers that often include multiple health care providers that address the various complex needs of patients. The dental model is private practice, including dental clinics, where Medicaid patients are rarely accepted owing to relatively low rates of reimbursement. As Otto reveals, dentists complain, accurately, that some Medicaid patients sometimes miss appointments and are generally more problematic. Those realities, however, reflect deeper issues of poverty and social class inequities that the private dental practice model cannot possibly address.

Otto extensively examines some reforms that could begin to address the serious oral problems affecting millions in the early 21st century. The medical model shows how midlevel practitioners have expanded health care to underserved communities for many decades. Nurse practitioners, paramedics, physician assistants and others all perform many routine health care procedures that do not require full training as M.D.s, and they work cooperatively and effectively with physician supervisors.

This approach has many advantages for dental treatment, especially for marginalized populations. Midlevel dental providers include dental hygienists and assistants, pediatric oral health educators, advanced dental hygiene practitioners and community dental health coordinators. They can, for example, create on-site dental clinics in emergency rooms throughout the nation or stand-alone clinics in neighborhoods that lack health care services generally.

The multiple procedures that trained dental professionals who have not achieved the full D.D.S. or D.M.D. educational level can perform competently include preventive education, dental examinations, cleanings, fluoride treatments, fillings and simple extractions. Otto notes that this model has been successfully employed for many years in many countries. Cheaper and faster to train, these dental therapists bring care to schools, geriatric centers and village clinics where people would ordinarily lack access to oral care.

The application to the United States is obvious. Its most extensive application is found in remote regions of Alaska, where Native children suffer from tooth decay at rates twice as high as other American children. And, as Otto reports, in that state, complete tooth loss by the age of 20 is not uncommon. Few fully trained dentists, with their private practice models, care to spend even part of their professional lives in such remote regions.

“Teeth” reveals the scarcely surprising fact that “[o]rganized dentistry has used its formidable financial and lobbying power to fight dental therapists.” The American Dental Association maintains that only fully qualified dentists should perform irreversible dental procedures. They appeal to principles of public health and safety and claim that lesser trained personnel may dilute the quality of dental care for their patients.

There is some merit to these concerns, but the real reason for the opposition is economic. One of the best features of this book is how it exposes the power of the dental establishment in its quest to preserve the wealth and privilege of its members. Otto reveals how dental leaders use their clout in Congress and in statehouses throughout the country. The ADA has tremendous resources and an army of lobbyists and policy experts to preserve its private fee-for-service model that advances regular and cosmetic dentistry for the privileged and leaves millions of Americans without dental care—the human consequences of contemporary capitalism.

Even Obamacare did little to address the problem of lack of access to dental treatment. Medicaid expansions were useless when Medicaid dentists were so hard to find. Now, with the Trump regime, both Obamacare and Medicaid are under attack, with problematic results in the near future.

Little of this matters in a nation that still refuses to acknowledge health care as a fundamental human right. That remains the larger struggle. Universal and full coverage, including oral care for all, must be the standard for a decent and humane society. Mary Otto, in “Teeth,” has moved this feature of that struggle into the arena of public policy debate.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.