Stephen Elliott: The Art of the Overshare

"The Adderall Diaries" author isn't one to hold back, as readers of his memoir -- not to mention his tweets, blogs, "overly personal emails," essays and online magazine, The Rumpus -- know well. Here, he opens up about his literary projects, his hyperlocal politics and the role of narcissism in his work.The self-reflective "Adderall Diaries" author opens up about his literary projects, his hyperlocal politics and the role of narcissism in his work.

A few weeks ago, Stephen Elliott shared some good news with his Twitter followers. Not only was his popular memoir “The Adderall Diaries” finally out in paperback, but the actor James Franco had just optioned it, with plans to write, direct and star in his movie adaptation of the writer’s own life story. Less than an hour later, Elliott followed up with a second tweet, asking, “But is he handsome enough?”

It’s a joke that fans of both the writer and the model-pretty movie star can appreciate, especially since Elliott has written so extensively of his adolescent physical insecurity and feelings of ugliness. In fact, over four novels, a collection of short-form erotica, a book of political nonfiction and countless articles, Stephen Elliott has written extensively about pretty much every aspect of being Stephen Elliott: the illness and early death of his mother, the constant abuse and neglect from his father, years spent on the streets, more years as a ward of the state, shuffling from group home to group home, several suicide attempts, heroin use, anorexia, the search for love and desire among strangers as a stripper, a complex fascination with bondage and sexual masochism. There is very little in his private life that he has not at some point Facebooked, blogged, tweeted, photographed, videotaped, podcasted or detailed to the 4,300 subscribers to his daily newsletter — a newsletter he himself refers to as his “overly personal emails.” If the malaise of modern Americans is our endless fascination with ourselves, as reflected and refracted through the lens of new media, then Elliott’s literary output to date seems to peg him as just another of the afflicted — an Internet-enabled narcissist and a poster child for Generation Overshare.

On the other hand, Elliott’s career also provides a compelling counter-narrative to the common lament that the contemporary urge to disclose generates nothing but more disclosure. After publishing his acclaimed autobiographical novel “Happy Baby,” Elliott parlayed his growing clout into monthly literary readings as fundraisers for progressive political candidates, which led to two star-studded benefits that brought his total to almost $500,000. He also wrote a nonfiction account of his time following Democratic candidates on the 2004 campaign trail, and edited four books, including a collection of short stories called “Politically Inspired.” He wrote several eloquent essays about teenagers like Alonza Thomas, one of the first juveniles to be tried under California infamously draconian youth sentencing law, Proposition 21. Thomas received 13 years in prison for a first offense. Elliott held a fundraiser for that cause as well.

Finally, after Arianna Huffington courted Elliott to edit a books page for The Huffington Post in 2007, he instead decided to start a site of his own. He launched the site with an original financial investment of $2,000 and the help of a few talented and dedicated volunteers, having enlisted accomplished authors such as Dave Eggers, Rick Moody and Antonya Nelson to provide occasional content and interviews or even regular columns, and collected submissions from countless writers and poets in his vast network (New Yorker writer Ariel Levy once called him “the most well-connected person in his income bracket”). Today, The Rumpus features book reviews, a frequently updated blog, a wildly popular advice columnist named Sugar, a variety of lesser-known writers and poets, and thoughtful political commentary which often focuses on topics that Elliott connects with personally, topics like poverty, the rights of sex workers, and the dangers of mixing money and art. There are also plenty of new-media experiments, including a new Rumpus books imprint, a series of podcasts and even a chat-enabled iPhone application for “The Adderall Diaries.”

Most important, Elliott’s success as both an author and a Web 2.0 literary publisher underscores an overlooked upside to the much-maligned American cult of the self, in particular when individuals, seeing themselves in the world around them, try to make positive changes in the world: Sometimes it takes an ego to build a village.

Elliott spoke with Truthdig from his office in the San Francisco Writer’s Grotto, and several times again over the phone, about his shift from national to local activism, the future direction of publishing, and the changing nature of community on the Web.

Sheerly Avni: The Rumpus is primarily a literary publication, but one with a strong political orientation as well. How would you define that orientation?

Stephen Elliott: There are a couple things. First off, we write about sex a lot more than any other literary publication, because we have a philosophy around sex as a major point of human motivation, and we believe that it is important to demystify sex. So if you don’t like that kind of stuff you shouldn’t come to The Rumpus. We do a lot of stuff around rights for sex workers, gay rights, gay marriage, and then sometimes a topic just hits us; for example we’ve been doing a lot of coverage of the oil spill. It just kind of depends, sometimes something just grabs us — but we do at least one political roundup a week.

Avni: But you don’t cover major news headlines.

Elliott: The Rumpus’ mission is in part to be a place you go to hear about things you wouldn’t hear of otherwise. The Internet was supposed to add this diversifying of content, and sure, that’s the case with lots of niche mini-blogs. But then among all the big magazines that get a lot of traffic, like Salon, Slate, Huffington Post, they are all talking about the exact same thing, because they’re chasing traffic.

There is a certain kind of culture that is created by marketing executives, and we have no interest in covering it. So we’ll never write about Britney Spears or Paris Hilton, not even in a “smart way.” That’s the kind of bullshit people try to get with on Slate or The New Yorker, where they say, “Oh it’s OK because we’re writing about them in smart and different way.” No, it’s not OK. You’re chasing traffic, and you’re pandering.

As for editorial vision, here’s an example, we have various quotes in our rotating toolbar, and early on, one of our writers was putting up negative posts, you know, jealous posts about other writers’ big book advances. So I put a quote in the rotating quote bar: “The Rumpus: Three celebrations for every complaint.” That’s a philosophy. We’re not gonna be the place to whine. There are a lot of good things you can find in the culture, and that we can celebrate. Avni: Well, the tone of The Rumpus is often celebratory. Or, at least, personal and friendly — there are lively comments sections, monthly gatherings, a book club, a strong focus on community, and especially on connection. You have said that there are two types of readers, those who read to escape and those who read to connect.

Elliott: Absolutely. There are different reasons people read, and different reasons people write. Some people write to be part of a literary tradition, because they love literature, they came upon some story when they were in college or high school, and want to be a part of that tradition.

And others who write to communicate. I mean, basically, they’re screaming and they are trying to write in such a way that will make you want to listen to their scream. … They’ve realized that if all they do is scream, you’ll put the book down, so instead they are trying to make something that actually gives back to the reader, because the reader is doing you this huge favor, so it’s kind of like you are making a bargain with him, or her: You’re saying, “I’m going to write something in such a way that you’ll enjoy it, and then you’ll do me the favor of reading it.” So my readers are the ones who were interested in connecting.

Avni: And connecting is both easier and harder in the age of the Internet.

Elliott: Certainly if you think of Web 1.0 and then back to old media before the Web came along. It’s like we were all sitting by the same river, and catching things as they passed. So there might be different groups, that were into things, but there weren’t so many rivers. But now there are streams and they are so small and so specialized, based on your microtunes and preferences and your ability to tailor all the information you are receiving and where you are receiving it from.

We lost community in writing when we lost the ability to all grab hold of that one book we could all talk about, because everybody knew that book, just the way everyone saw “Seinfeld” because there were only three channels. … There [later] were more points of connection, so now, with so many more channels, outlets, websites, there are fewer things people have in common that they can talk about. And Web 2.0, at least in part, in my opinion, has risen as a response to the community that was lost during Web 1.0. Community is the one thing, the one idea, the one that has just completely overwhelmed everything else.

Avni: What does community mean to you?

Elliott: Community is people sharing common interests — things that you care about. It used to be, for example, if you were into S&M but you lived in a small town you were never going to meet someone who had similar desires, because how would you find out if they did? You were part of this subgroup only a fraction of the population belongs to, so it was very difficult for most people to find someone to talk to. … There were some communities, but the majority of people who were into bondage or S&M or extreme S&M, the smaller the group the harder it was to find, so much so that most people just accepted that they wouldn’t. Whereas, the Internet makes it possible to meet people that are into anything you are into. Going to see a prostitute is a very private thing, but now there are whole discussions, where people are trading discussions back and forth about sex workers they’ve seen.

Or community forms around a book. People don’t just want to read a book, they want to talk about it. But with literary books, we’re talking very small readerships, very small publishers. There are probably more writers of literary fiction right now than readers. OK, that’s a joke but it’s also a little bit true. And before, you had to suck it up, read the books you liked, and accept the fact that you wouldn’t have anyone to talk to about it in your small town.

Now it’s different. So how do these people find each other to talk about these books they like to read? How do they connect and share their experience? That’s community — and thanks to Web 2.0 people expect community around everything they do now.

Avni: For a long time, you focused less on these kinds of questions in your work and more on big issues: political campaigns, the war, Obama. And in 2007, after years of activism, you wrote an essay for The Believer in which you described the political arena as “the worst of human nature on display under glass.” You compared it to a schoolyard, “just a bunch of hurtful insults, character destruction, power grabbing, and coalition building. Meaningless, but with consequences.”

Elliott: I really burnt out on national politics. I don’t know if I’m a person who can effect change on that large of a level. But then hyperlocal politics really grabbed me and I was like, oh, there it is. I found that I found it being replaced by the American Apparel campaign, when we fought, successfully, to keep American Apparel from opening a store on Valencia Street in The Mission, which is where I live in San Francisco. And that was as satisfying as anything I’d ever done.

Avni: Well, it’s also your own neighborhood.

Elliott: I would feel weird protesting in someone else’s neighborhood! But the important thing about this is that we started campaigning only 17 days before the planning commission hearing; it was real fast, and that’s why nobody was fighting it [the plan to open the store], because they thought there wasn’t enough time. But it was like throwing a match in a barrel of cotton, it just lit right up. People took to the streets, and all you had to do was make some posters and set up a website and it was on.

Avni: What are some other issues coming up?

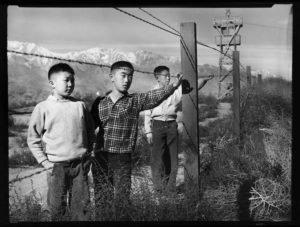

Elliott: Definitely Sit/Lie, which is a proposition to criminalize homelessness in San Francisco. That impacts me quite a bit, because I would have been arrested under this law for sitting in front of a closed business between the hours of 7 a.m. and 11 at night. Says homeless people aren’t allowed to sit down. Everyone else can just go to the coffee shop, and take a break. Basically, that’s just crazy. Avni: So clearly much of your activism is based on things you learned through your own experience. What [is the significance of] the difficult period in which you lived on the streets or in group homes? How much has it shaped you, as an artist and as a person?

Elliott: There’s this way in which group homes were great, and then there’s this way in which they did a lot of permanent damage. When I was 14 and sleeping on the street I never had to go home. I could stay out at every party; no one was ever going to tell me what to do. That was great in a kind of way, it taught me about being independent. People tell you, you can’t do things. And it turns out you can. If I’m in this abusive home, the common wisdom is I have to stay there. No one is saying that I can just leave and sleep on top of the convenience store. But in fact I can. And learning that at an early age had a really strong impact. A lot of times people will say, “Oh, you can’t do that.” And my response is, “Well, I think I can do that.”

But beyond that, people always ask me that, since I’ve also written a lot of erotica, people always say, “Aren’t you worried about being pigeonholed as an erotica writer?” And I always say, who is going to pigeonhole me? You can only pigeonhole yourself. You can do anything you want. This idea that other people are somehow in control of what you are creating, what you are allowed to create, and that is just not the case. You have to live within your own framework, set up moral boundaries for yourself that you don’t trespass so that you are able to look at your actions and say “I’m comfortable with what I did here.”

Avni:

Do you think that early kind of “I-can-do-that” thinking has contributed to some of your success today?

Elliott: Well, I’ve been able to do all these creative projects, yes, but there is a tradeoff. I don’t have children, I’m not married, nobody relies on me for everything. But people think they should have everything: They should be able to live in a house, and have children, and be a writer. But I don’t really agree with that. I don’t think you should be able to have children and be a writer. Good if you’re able to pull it off — I don’t think there’s some sort of social contract around that. I don’t think people owe you money for being a writer. I think all you’re owed for being a writer is health insurance and a small room.

Avni: So writers are owed health insurance?

Elliott: [Laughs] Yes, but only because everyone is owed health insurance. As an artist, the first thing you should be prioritizing is the work. If you put money before the work, that’s problematic. But what I have a hard time with is people who are trying to create art, and who want other people to fund it, and who then feel this bitterness because they don’t have a lot of money. They want to do their art full time and think society should pay for it. I mean I’m happy for anything I get, and I’ll try and negotiate the best price I can. But I don’t think that anybody owes me. I’m doing what I would do naturally as a writer, and writing pretty much anything I want. That’s the gift right there.

Avni: You obviously write quite a bit about yourself. About halfway through “The Adderall Diaries,” there is a passage in which two separate friends tell you it’s time to branch out, quit writing about your own life. How did you take that feedback?

Elliott: The book itself answers your question, you know what I mean? They told me “you gotta stop writing about yourself,” and then I wrote about them saying that, and I wrote about myself thinking about them saying that — and I put in my memoir!

Avni: How then does narcissism play into your writing?

Elliott: It’s an interesting question. Was Kerouac narcissistic? Was Hemingway, was Sylvia Plath? Did these people think their experiences were particularly interesting and important? I think if anyone is creating art from their life, is a narcissist, anyone who makes art from their life is a narcissist, but the question is: Are they making good art? You can write about yourself, and use your life as paint, the way the artist uses paint on a canvas. … It’s just a tool, it’s just another brush, or a color of paint. The piece neither succeeds nor fails because you’re in it. The piece will succeed if the writing is good.

Avni: So if you want to be a great stripper you better look good and dance well, and if you want to be read, you’d better write well.

Elliott: Yes. Do you have enough self-knowledge, are you introspective, do you recognize the way culture plays a role in your world, is all of that there in a way that will permit you to make decent art that will illuminate someone else’s world? So if you’re writing about yourself, but you’re not questioning things, being critical of your own motivations, and you think you’re inherently interesting because the writing is about you, then you’re in trouble. Because in the end, it doesn’t matter how narcissistic you are, so long as you remember that the most important person isn’t you. The most important person is the reader.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.