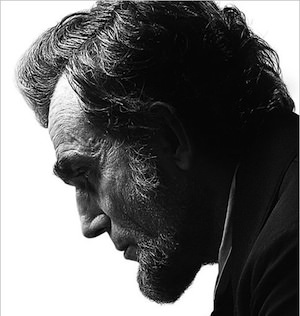

Spielberg’s ‘Lincoln’ Is Honestly Good

Lincoln is inherently a static and talkative subject that Spielberg has triumphed over not through avoidance, but by embrace. Lincoln is inherently a static and talkative subject that Spielberg has triumphed over not through avoidance, but by embrace.

When Steven Spielberg was 7 or 8 years old, his uncle took him to Washington, D.C., to see the historic and patriotic sights. The one that impressed him most was the Lincoln Memorial. “I was very little and Lincoln was very big, sitting on that throne, that great chair,” he recalls. “I was very intimidated by it and almost couldn’t make eye contact with the figurehead.”

Spielberg was, at the time, mildly dyslexic, but he found that his reading troubles disappeared when the subject was Lincoln. Perhaps he didn’t fully realize it at the time — any more than he realized he was going to be a film director — but an obsession was born. Now, after almost 60 years, his obsession has at last borne fruit: “Lincoln” is upon us and it is close to being a great film — beautifully acted, sober in intent and, above all, a passion project that represents an unwavering, virtually lifelong, commitment to an enterprise that is not, on its face, a natural screen subject despite the many Lincoln films over the years.

Let’s face it: Lincoln is inherently a static and talkative subject that Spielberg has triumphed over not through avoidance, but by embrace. Through the years, many scripts were written, all of which were found wanting. It was not until he turned to playwright Tony Kushner, who earlier wrote “Munich” at Spielberg’s behest, that he began to hear Lincoln’s voice, perhaps a little too fulsomely; Kushner’s first draft was more than 500 pages, nearly five times the customary length of a screenplay.

The topic became narrowly focused: The film is chiefly about Lincoln’s attempt to pass the 13th Amendment to end slavery. And a lot of its glory derives from the fact that it grants the issue’s full complexity. Politically, it is a vexing matter, and the movie utterly refuses to simplify it. We have to attend its arguments very carefully. Yet — and this is very much to its credit — they are clearly stated. I cannot readily summon up another movie that deals with an issue, now fairly obscure except to historians specializing in this field, with greater force of detail. Or passion. These people — notably Lincoln — care about this matter and their passion is clarifying. They do not get lost in their arguments and neither do we.

That has a lot to do with the acting, notably Daniel Day-Lewis’ Lincoln. Research has taught him that Lincoln had a rather high, thin voice. The noble resonances and bearing of, say, Raymond Massey are not for him, and this naturalism is a huge, humanizing aid to his characterization. He can, for example, easily tell a funny story and there is no patronizing about it. He is likable, but never seems to be using us for our favor when the mood for drollery overtakes him.

Yet there is steel in the man. He will have what he must have, and what the country must have, in his judgment, and he beavers away tirelessly to assert his will on his “Team of Rivals,” to quote the title of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book, which is one of the film’s sources. His work is unforced, even easeful at times. It is a great performance, yet one that never once admits that it is going for greatness.

The same may be said for Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln. It is, more or less by common consent, a thankless role but not in Field’s playing. She is much more helpmate than termagant, a woman of spirit, passion and — who would have guessed? — an affectionate nature. At least in this telling, all is well with the Lincoln marriage and the movie is the better for it. Honest Abe had enough troubles without adding a difficult marriage to the list.

What can be said of Field can be said of the rest of the cast — David Strathairn, Hal Holbrook and, most notably, Tommy Lee Jones as a marvelously bumptious Thaddeus Stevens. You could argue — fatuously, I think — that this bold performance is out of key with the rest of the picture, but Jones is on it when it comes to a wayward and hilarious life that goes a long way toward rescuing the film from the danger of being merely earnest and high-minded.

That is not a flaw that the film succumbs to; it is merely a risk that it runs. And avoids. I don’t suppose that Spielberg ever thought that “Lincoln” would be one of his mightiest hits. It was clearly never imagined to be an “E.T.” or “Indiana Jones.” It’s too thoughtful for that — too staid and too static. He wants it to be that way. If, occasionally, our attention wanders from its closely reasoned arguments, it soon wanders back.

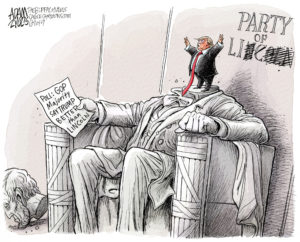

There was a time when films of this quality and character were not as rare as they are now, when directors of Spielberg’s talent and ambition thought it was an obligation to make movies that were not meant to be huge hits, that spoke to their passions or, rather, their obsessions. Spielberg has a good record in that regard. “Lincoln” is a hard movie to like, in the conventional sense of that term. But Spielberg is, I think, a better man for having made it. And we will be the better for seeing it, as ultimately we must, if we care about a cinema that is something more than heedless and headstrong. In its way, this film is one of Spielberg’s riskiest. It deserves our attention and regard.

Correction: An earlier version of this review accidentally said Lincoln was attempting to pass the Emancipation Proclamation. This was a slip of the tongue. The film takes place during the attempt to pass the 13th Amendment in the House of Representatives.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.