Sanders Bets Big on Medicare-for-All

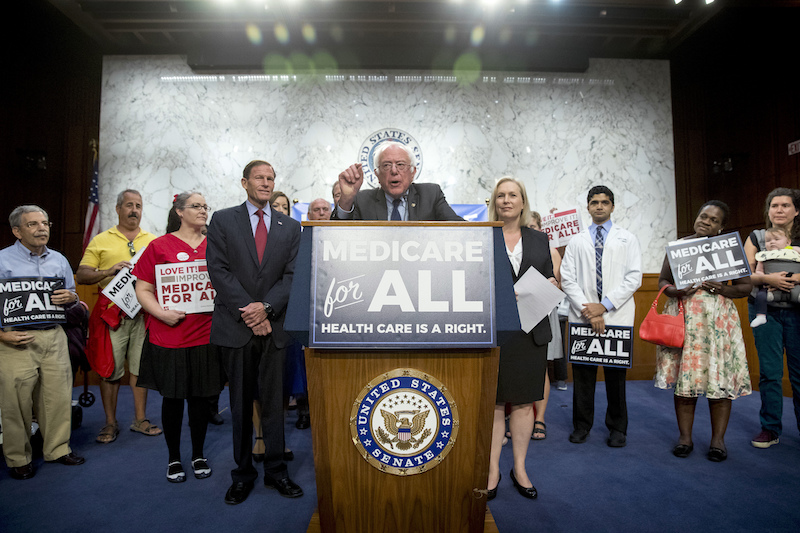

The health care revolution the Vermont senator boosted in 2016 seems even more crucial, to him and Americans, this time around. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., center, joined by Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., center left, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., center right, and supporters, speaks at a news conference in Washington, D.C. in September 2017, to unveil their Medicare for All legislation. (Andrew Harnik / AP)

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., center, joined by Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., center left, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., center right, and supporters, speaks at a news conference in Washington, D.C. in September 2017, to unveil their Medicare for All legislation. (Andrew Harnik / AP)

The 2019-model Bernie Sanders has aged well, looking as spry as he did four years ago. His speeches are the same, too. But where they were once dismissed as too radical, they are now mainstream, clearly focusing on the ills of an America that has grown more inequitable since he last ran for president.

Those were my impressions when I joined about 12,000 others last week and heard him speak at Grand Park, a big grassy space across from Los Angeles City Hall.

The ability of his organization to build such a crowd in a city accused—wrongly—of political apathy was impressive. Almost a year shy of the California presidential primary, Sanders’ team had assembled an email network and social media connections, recruited and deployed dozens of volunteers, relentlessly contacted lists of potential supporters, and moved them into long lines, patiently waiting to enter the park.

“Not only are we going to win California, we are going to win the Democratic nomination,” Sanders shouted. But one rally does not make a campaign.

Beyond the park, as well as beyond the city limits, are the millions of victims of an economy and society growing progressively more unequal. Draw a circle around Grand Park on a map of metropolitan Los Angeles and it will encompass all the ills of an inequitable America. To the east is skid row, with streets crowded with homeless people. Farther east and south and west are crowded neighborhoods where immigrants and native-born share poverty and send their children to public schools unable to equip them to earn a living wage in a cutthroat, competitive, technically oriented world. Bad health, inadequate diets, a shortage of physicians and nurses and the need to work two or three jobs to survive add up to insurmountable barriers.

Extend the imaginary circle to the entire country, and it will include urban centers and the unemployed and underemployed residents of rural counties in the grips of the epidemic of drug deaths and suicide.

The coming election is about these people. Some are Trump voters, some are not. Among them are the many victims of the huge gap between the rich elite on top and the growing number of poor people.

I’ve always thought that health care is the issue that encompasses every aspect of this inequality, a belief that has been strengthened each time I visited a county hospital or a clinic. Without the certainty of care, millions are a step away from financial ruin and death. “For the third straight year, life expectancy in America is in decline,” Sanders said at the rally. “We are going to change that.”

During the event, I talked to people about health care. I approached two women, Sandy Reding and Rebecca Prediletto, who were wearing the red shirts of the California Nurses Association. Their union was a major force behind Sanders four years ago, embracing a concept then ridiculed by cautious Democratic mainstreamers: Medicare-for-all. Earlier in the week, Sanders had spoken at a nurses union rally at UCLA, where the nurses had staged a one-day walkout in support of members in other parts of the state.

This particular Saturday was the day before the revelation of the report giving President Trump so-called exoneration in the Russian investigation. But, as the Democratic victories in last year’s House elections showed, health care means more to voters than the president’s relations with the Russians. The following week, Trump, scorning the election results, moved to kill Obamacare.

“We’ve been on the ground canvassing for Medicare-for-all,” Reding said. Their reception, both nurses said, was much different than it was four years ago. “It’s the difference between night and day, ” she said. “These are people who come out after they have done their research. Medicare-for-all is the fire-starter, the catalyst.”

It is a catalyst because guaranteed medical care, as represented by Medicare-for-all, would bring about a great improvement in American life on many levels. Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act, has already made life better. I saw that when community health care clinics for the poor began to expand immediately after President Obama signed the law that will always be identified with him. Just a few weeks before, these clinics had feared closure or sharp reductions.

The Center on Budget Policy and Priorities estimates that 20 million Americans have gained coverage by receiving Affordable Care Act subsidies since Obamacare became law. That’s in addition to young people who have been added to the rolls, the new eligibility of those with pre-existing conditions and recipients of Medicaid.

Obama made major compromises to win approval for his proposal. This left defects in the program. His efforts to remedy them failed because of Republican opposition and Democratic inability to agree on a fix.

Improvements have been proposed by congressional Democrats. A simple cure would be to increase the subsidy, leaving in place Obamacare’s complex system of private insurance, public “marketplaces” and a variety of plans with different costs and benefits. Even simpler would be to eliminate private insurance, including employer plans, and provide health insurance through a single government plan. That’s Medicare-for-all.

It would be a federal government-administered program providing coverage to all U.S. residents. “Medicare-for-all would result in a major shift in the way in which health care is financed in the U.S.—away from households, employers and states to the federal government and taxpayers,” the Kaiser Family Foundation says.

This would be a revolution, now impossible to accomplish with Republicans in control of the presidency and the Senate. In addition, those with employer-provided insurance might be reluctant to give it up. Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren and other Democrats favor a two-track approach, making fixes in Obamacare while fighting for Medicare-for-all. Sanders wants to go all the way as soon as possible.

Trump’s alternative is brutal. It’s hard to imagine the harm it would do the country if he succeeds in killing Obamacare. “More than eight years after enactment, ACA changes to the nation’s health system have become embedded and affect nearly everyone in some way,” according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The numbers of people who could lose coverage if Trump succeeds are staggering. It would return control of health insurance to the insurance business, famous in pre-Obamacare days for whom it would not cover.

The Kaiser Family Foundation says 17 million poor Americans could lose Medicaid coverage and 15 million others could lose ACA subsidies that now help pay for policies. The foundation says 52 million people have pre-existing conditions that are now covered by Obamacare but would not be included if it is repealed. Higher rates for women could return. Preventative services mandated by the ACA could be lost, including screening for breast, colon and cervical cancer and pregnancy-related services, such as contraception. The requirement for insurance companies to pay for essential services could be lost. Among these are mental health and substance abuse treatment. Such illnesses, experts say, are largely responsible for Americans’ decreasing life expectancy.

Think of all these numbers as human beings. It’s easy to forget about them with the news media transfixed on finding out whether Trump and his shady team tried to cover up electoral and business wrongdoings. But these potential victims of Obamacare repeal were heard during last year’s election, when they helped the Democrats win the House.

Four years ago, even two years ago, these concerns were not a major part of the political debate. Growing income equality changed that. The poor, as well as members of the working class and middle-class, white-collar sectors, find themselves in the same boat, too many of them in the gig economy, working part-time, one illness or injury away from disaster.

“The ideas we talked about were considered by mainstream politicians as much too radical,” Sanders said at the Grand Park rally. “Well, brothers and sisters, a funny thing happened in the last two years. … Now it is our job to complete the revolution.”

I don’t know whether Sanders can win. With so many Democratic candidates floating around, it’s too early to talk about that. But in a Los Angeles park, filled with supporters, Sanders no longer looked too radical—and his victory didn’t seem so improbable.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.