Rosa Parks: A Life

Nearly 60 years after the Montgomery Bus Boycott comes "The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks," the first scholarly biography of the woman who risked much and spoke little.

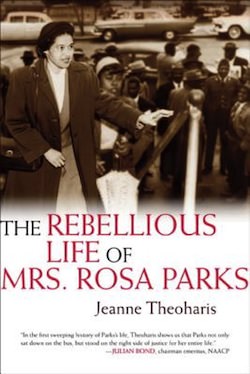

“The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks”

A book by Jeanne Theoharis

In 1960, Jet magazine sent a correspondent to interview Rosa Parks. Five short years had passed since Parks had famously refused to move to the back of the bus, with her arrest triggering a series of events — the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the elevation of Martin Luther King Jr. to the national stage — that would radically reshape the 20th century. But when the Jet reporter caught up with Parks she was living in Detroit, described as a “tattered rag of her former self — penniless, debt-ridden, ailing with stomach ulcers and a throat tumor, compressed into two rooms with her husband and mother.”

If the image is jarring, it is a testament to how little we actually “know” about one of the best-known women of American history. The boycott had been a remarkable victory, but it offered precious little relief for Parks. She had been fired for her activism and was supporting her husband, who had suffered a nervous breakdown and turned to drink under the stress of constant death threats. Though she had sparked the boycott and tirelessly traveled the country to raise funds in support, civil rights leaders in Montgomery, Ala. — unable to consider women equal partners in the struggle — never offered her a job. And so eight months after the city’s bus lines were integrated, Parks and her family, who had called Montgomery home for 25 years, fled to Detroit, never to return.

Such details clang against the conventional narrative of Parks. Applauded today by politicians of all stripes — this alone should arouse considerable suspicion — her life has become a sort of chicken soup for the American soul, a feel-good story that is short on details and heavy on sentimentality. Even the most pertinent fact, her radical and lifelong activism, is discarded in this telling. Instead, Parks is depicted as an apolitical figure approaching sainthood in her purity: humble, quiet and spontaneously moved to take a stand when confronted by a glaring injustice. If anyone has ever needed “extrication from a pile of saccharine tablets and moist hankies,” as Christopher Hitchens memorably remarked about George Orwell, it is Rosa Parks.

Nearly 60 years after the boycott, we now have our first scholarly biography of Parks. “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks,” written by Brooklyn College professor Jeanne Theoharis, seeks to reveal a character that “continues to be hidden in plain sight, celebrated and paradoxically relegated to be a hero for children.” Theoharis, who previously studied civil rights activism in the North, dives deep into the archives to return with a nuanced if somewhat plodding portrait of a dedicated activist who managed to be both an iconic figure and an everywoman of the civil rights movement.

|

To see long excerpts from “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks” at Google Books, click here. |

For a biographer, Parks is far from an ideal subject. A collection of her papers has been caught up in a legal fight and is now in the possession of Guernsey’s Auctioneers, where they sit in a Manhattan warehouse. (Unforgivably, the auction house has refused scholarly access to the documents.) There is also Parks’ own sense of decorum, which prevented many of her private feelings from finding public expression. “My problem is — I don’t particularly enjoy talking about anything,” she once admitted. During interviews she tended to carefully choose words and deflect attention, repeating the same stories when asked the same questions. “Finding and hearing Rosa Parks has not been easy,” Theoharis notes. When the book hits dead spots — and there are several — it is usually because the voice of Parks refuses to pop. As a black woman who cut her activist teeth in Alabama in the 1930s, she learned early on to say only what needed to be said. “Is it worthwhile to reveal the intimacies of the past life?” she wrote on a scrap of paper sometime after the boycott. “Would the people be sympathetic or disillusioned when the facts of my life are told?”

The facts of Parks’ political life took shape in a working-class family. Her grandfather was militant in his black pride. Born into slavery and beaten regularly as a child, he quite understandably held a “somewhat belligerent attitude toward whites.” After World War I, when Klan terror intensified, he would sit on the porch with his rifle, waiting almost happily for any invaders. Parks would join him on his vigil — “I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer,” she recalled — but Klansmen were smart enough to stay away.

After marrying, Parks got involved with the NAACP. She became secretary of the Montgomery chapter and worked with E.D. Nixon, an autodidact and local activist who became the chapter’s president. The pair spent much of the 1940s transforming the NAACP into a fighting organization, helped along by Ella Baker, one of the movement’s greatest strategists. Parks spent much of her time traveling the state to document and protest violence against blacks, the kind of work that usually goes nowhere and requires an almost superhuman optimism. Several years later, Parks organized the NAACP’s youth council, which protested segregation and included among its members a young teen named Claudette Colvin. Nine months before Parks’ arrest, Colvin would be booked for refusing to move to the back of a bus. Colvin was a brash teenager — and pregnant by a married man — and leaders were less willing to rally to her cause and launch a boycott.

The myth of Parks as apolitical, then, can be quickly discarded. Indeed, the summer before her arrest she attended a two-week workshop at the interracial Highlander Folk School in Tennessee whose topic was “Racial Desegregation: Implementing the Supreme Court Decision.” But there’s another myth concerning the “spontaneous” nature of the boycott that Theoharis demolishes. The boycott was in fact a long time coming. In 1954, Jo Ann Robinson, president of Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council, sent a letter to the mayor that diplomatically warned of a boycott if the buses remained segregated. When Parks was arrested a year and a half later, the WPC — which had been eagerly awaiting such a development — sprung into action, printing and distributing thousands of notices announcing a boycott. Like much of the civil rights movement, the boycott was driven by women through and through: sparked by Parks, called for by the WPC and made possible by the broad networks that female activists had created throughout the city.

Yet at nearly every turn, as Theoharis skillfully recounts, female leaders were marginalized. During a mass meeting on the first night of the boycott, a string of men took to the stage to speak, but despite calls from the crowd, Parks was never allowed to say a word. “You’ve said enough,” she was told. Not much had changed eight years later at the March on Washington, when not a single woman would address the crowd. Organizers defended the decision by explaining that choosing any one woman would alienate others. “The idea that multiple women might speak was too far-fetched to contemplate,” Theoharis observes.

Parks was no doubt angered at such slights, but her loyalty to the movement — and her tendency to keep some thoughts private — caused her to air criticism in an oblique manner. “I think everyone spoke but me,” is how Parks remembered the mass meeting in Montgomery. About the exclusion of women from addressing the crowd at the March on Washington, she told fellow activist Daisy Bates that she hoped for a “better day coming.”

Here is where the personality of Parks can make for frustrating reading. She was bright; she was a keen observer; and she possessed both uncommon guts and a deeply rooted sense of self-worth. Her activism too was far to the left of what is commonly assumed: She cited Malcolm X as her hero and supported a number of Black Power causes in Detroit, where she would finally enjoy some measure of economic stability while serving as an administrative assistant for Congressman John Conyers. But throughout her long life, she never fully opened up (unless, of course, within the unseen documents held by Guernsey’s). She was, as Theoharis writes, “a kind, unassuming woman, raised in the church and in the Southern traditions of good manners and public dissemblance.” A thoroughly political actor, she did precisely the opposite of most politicians by risking much and talking little. We may never know the intimate contours of her thoughts, or exactly what she went through — “There’s plenty I have never told,” she once admitted to a reporter — but we know what she gave us, and that’s more than enough.

Gabriel Thompson has written for The New York Times, New York, The Nation and Mother Jones. His most recent book is “Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won’t Do.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.