Remembering Norma Barzman, Last of the Hollywood Blacklistees

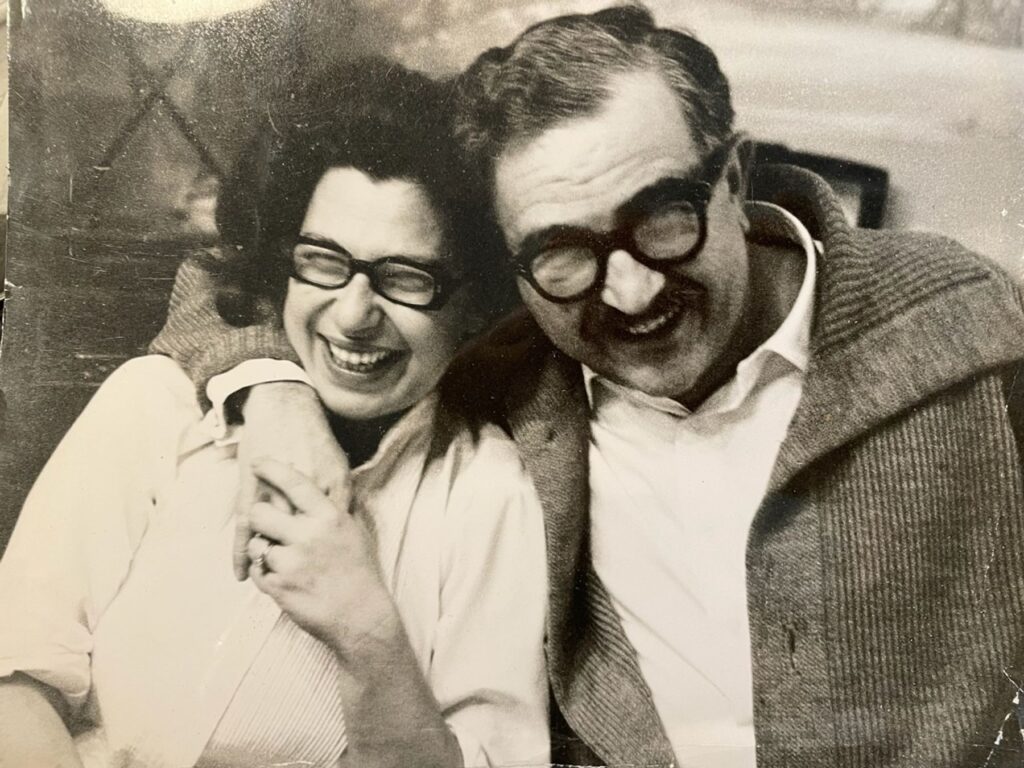

A victim of the 1940s Reds-under-the-beds hysteria, the feisty screenwriter went into exile and held firm to her values. Norma Barzman. (Photo: Courtesy of Barzman family)

Norma Barzman. (Photo: Courtesy of Barzman family)

Screenwriter and author Norma Barzman died Dec. 17 at the age of 103. A lifelong progressive who joined the Communist Party USA in the 1940s, Norma was the last survivor of the Hollywood Blacklist, when leftists and anyone who refused to become an informer were purged and barred from the film industry until the passing of Reds-under-the-beds hysteria in the 1960s.

My initial encounter with Norma was like a “meet cute” scene straight out of a Nora Ephron comedy. In February 2002, I was assigned to cover an exhibition called “Reds and Blacklists in Hollywood: Political Struggles in the Movie Industry,” presented at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Beverly Hills headquarters and curated by historian Larry Ceplair. As a contributor to New Times LA’s “The Finger” column, it was arranged for me to meet four blacklisted screenwriters at the event, which the Academy intended, in part, as a mea culpa after decades of turning its back on persecuted artists. The quartet included Jean Rouverol, Bernie Gordon, Bobby Lees and Norma.

All four of the interviewees left Hollywood because of the Blacklist. Lees relocated to Arizona; the others all moved abroad. Rouverol spent time in Mexico with fellow Blacklistee Dalton Trumbo; Gordon wrote epics and horror movies in Spain under assumed names. Norma’s exile lasted the longest; she lived mostly in France from 1949 to 1976.

During the Blacklist and beyond, the Hollywood Reds had been reviled with barrels of bad ink, and it took Norma a long time to get over her anger and distrust of me.

The interview went well, with the octogenarian blacklistees mixing praise for the exhibit with criticism of the Academy for its reactionary role during the Red Scare. This role included denying screenwriters those coveted golden statuettes won under their real names, awarding them instead to fronts or pseudonyms for writers who didn’t exist. After the interview at the Academy’s HQ, I photographed the foursome standing in front of one of those elusive, larger-than-life Oscars, with a beaming Norma in front. They all impressed me, but I was especially taken by the vivacious, feisty Ms. Barzman.

We parted on friendly terms and I proceeded to write an evenhanded column about the subjects and the Academy’s “Reds and Blacklists in Hollywood” show. The published version of my story, however, included few if any of the positive quotes; what remained was almost entirely negative. In his drive to amp up the column’s “gotcha” tone against the Academy, New Times LA’s editor left the blacklistees’ positive comments on the cutting room floor.

Norma was initially incensed by the one-sided negativity of the published column and unmoved by my explanation. During the Blacklist and beyond, the Hollywood Reds had been reviled with barrels of bad ink, and it took Norma a long time to get over her anger and distrust of me. Eventually, however, she did, and we became friends and co-workers on blacklist related projects. After all, even Orson Welles , she reminded me, lost out on final cut in “La-La-Land.”

Norma Levor was born into an upper crust Jewish family on Sept. 15, 1920, in New York City. Named after the title character in Bellini’s 1831 opera “Norma,” she grew up mostly in suburban Westchester. After her father Samuel died, in 1941, she moved to Los Angeles with her mother and older sister Muriel (Columbia Law School’s first female graduate) to join a cousin named Henry Myers, who worked as a screenwriter and was a founding member of the Screen Writers Guild (now the Writers Guild of America) and the Hollywood chapter of the League of American Writers. Henry co-wrote the 1932 W.C. Fields comedy “Million Dollar Legs,” and in 1939 shared the writing credit on “Destry Rides Again,” and he influenced Norma politically and creatively.

Henry also helped recruit Norma’s husband, Ben Barzman, into the Communist Party. The two met at a Russian war relief fundraiser in 1941 hosted by writer/director Robert Rossen, who’d go on to helm classics like 1947’s “Body and Soul,” 1949’s “All the King’s Men” and 1961’s “The Hustler.” The fundraiser at Rossen’s Beverly Hills home included a who’s who of the Hollywood Left, a milieu of creativity and conscience that enchanted Norma throughout her long life. Both Rossen and Barzman were CPUSA members on the night Norma met her future husband.

Later, during a date at the Brown Derby, Ben explained why he and others of his generation had joined the Party. According to Norma’s 2003 memoir, “The Red and the Blacklist,” Barzman told her, “I grew up during the Depression. Communists led the struggle for the unemployed. They unionized workers. They fought for Negro rights and against injustice wherever it existed.”

Ben also told Norma about the role radical scribes played in Tinseltown. “We’re making a difference,” he said. “We influence producers to make pictures about real people. About women. We keep out the ‘Stepin Fetchit’ characters. Movies are less bad because of us.”

In 1946, Norma had her first big breaks, co-writing the Errol Flynn romantic comedy “Never Say Goodbye” and the film noirish “The Locket” starring Robert Mitchum.

The Barzmans were married by a defrocked rabbi on Jan. 25, 1943. Norma joined the CPUSA during WWII, telling Ceplair in the 1997 book, “Tender Comrades,” “the Soviet Union had been invaded; the Russians were fighting the Nazis and were our allies. Then it seemed normal to be working alongside the Communists.” A feminist, Norma was also “attracted… to Communism [because] Soviet women were allowed into all the professions. It appeared that the Soviet Union had a better attitude toward women than any other country.”

During this period, Norma developed as a writer, reporting for the Hearst-owned Los Angeles Examiner. She attended Marxist study groups and studied screenwriting at the School for Writers run by the left-wing League of American Writers. Her teachers included Gordon Kahn, who would later become one of the “Hollywood Nineteen”, and John Howard Lawson, first president of what’s now the Writers Guild of America, reputed head of the CP’s Hollywood branch, and first member of the “Hollywood Ten” to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947.

In 1946, Norma had her first big breaks, co-writing the Errol Flynn romantic comedy “Never Say Goodbye” and the film noirish “The Locket” starring Robert Mitchum. Along with being well-written, the latter’s intricate use of flashbacks was innovative for its time.

Meanwhile, Ben’s screenwriting career had also blossomed. He co-wrote 1944’s populist picture “Meet the People,” starring Lucille Ball, Dick Powell and Bert Lahr, and 1945’s WWII morale booster “Back to Bataan,” starring John Wayne and directed by Ben’s fellow Communist Edward Dmytryk. In 1948, he co-scripted a parable about racial prejudice, “The Boy with Green Hair,” starring Dean Stockwell and helmed by another CP’er, Joseph Losey.

With the Allies’ WWII victory over fascism, the U.S.-U.S.S.R. alliance came to an end, and the Cold War started.

The heat on La-La-Land’s leftists began by October 1947 with the opening of HUAC’s Hollywood Ten hearings. Not long afterwards, Groucho Marx and Marilyn Monroe warned the Barzmans at their West Hollywood home on Sunset Plaza Drive that they were being surveilled. Fearful they’d be subpoenaed to testify, the Barzmans fled to England to shoot “Christ in Concrete” (aka “Give Us This Day”), a 1949 proletarian drama co-written by Barzman and directed by Dmytryk, who, along with the rest of the Hollywood Ten, was facing prison time for contempt of Congress. (He eventually served his time, but later recanted his HUAC testimony and became an informer to continue directing movies in Hollywood).

Rather than confront what the Hollywood Ten’s Alvah Bessie called the “Inquisition in Eden,” the Barzmans relocated to France. There, Norma says in “Tender Comrades,” “French intellectuals, whether Communist or not, treated us like heroes. As a result, we had a good feeling about ourselves… They believed that by standing up to HUAC we had done something wonderful.” One of those artistes was the Spanish-born Pablo Picasso, who embraced the Barzmans as fellow “exiles.” After they moved to Mougins in the south of France, near Picasso’s studio at Vallauris, the Barzmans became fast friends with the legendary painter as well as with other leftist French cultural icons, including actors Yves Montand and Simone Signoret.

Rather than confront what the Hollywood Ten’s Alvah Bessie called the “Inquisition in Eden,” the Barzmans relocated to France. There, Norma says in “Tender Comrades,” “French intellectuals, whether Communist or not, treated us like heroes.”

The first informer to identify the Barzmans as Communists to HUAC was screenwriter Leo Townsend in 1951 (other snitches followed suit). However, living outside the repressive U.S., Ben was able to avoid appearing before the Committee and pursue his screenwriting, including Losey’s UK-shot 1957 “Time Without Pity,” and epics such as 1961’s “El Cid” starring Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren, 1964’s “The Fall of the Roman Empire” with Loren, Alec Guinness, and Christopher Plummer, and 1966’s WWI aerial combat movie, “The Blue Max.”

The Barzmans had seven children, and given their precarious immigration status, the uprooted Hollywood Reds avoided politics. Nikita Khruschev’s denunciations of Stalin’s crimes, the USSR’s crushing of Hungary’s uprising and a disillusioning visit to Russia cooled their ardor for the Soviet Union. Still, Norma would later say she drew political and creative inspiration from France’s almost-revolution of May ’68.

More than a quarter century after fleeing America, the Barzmans returned to Hollywood in 1976. In “Tender Comrades,” she called the move back “a shock — the community had disappeared.” Gone was the Hollywood Left milieu Norma had once thrived in. It had been replaced by a culture of “what have you done for me lately?” Ben, a decade older than Norma, passed away in 1989.

She began a new chapter by writing a column on aging for the L.A. Times, “The Best Years.” In 1999, Norma returned to politics by participating in protests against the Academy’s awarding an honorary Oscar to Elia Kazan — who Victor Navasky described as the Blacklist’s “quintessential informer”. In 2003, Norma published “The Red and the Blacklist,” joining the ranks of blacklisted leftists turned memoirists. Although her saucy account has a tell-all quality, detailing numerous extramarital liaisons, the book “also turned her into a figure of resistance during the George W. Bush era,” according to daughter Luli Barzman.

The book’s juicy details about her decades of hobnobbing abroad with Europe’s lefty glitterati led some to criticize Norma for making the Blacklist sound like it really wasn’t so bad (at least for her). But this is unfair. Norma’s budding screenwriting career in Hollywood was preempted by her persecution and forced exile. How would it have helped the 300-plus other victims if the Barzmans had suffered further by remaining to face the HUAC music?

In early 2017, as the 70th anniversary of the Hollywood Blacklist was nearing, I approached Norma about staging a commemoration. We met to discuss it at her Beverly Hills apartment, decorated with original artwork by her pal Pablo. My concept was simple: invite survivors and relatives of artists persecuted during the Blacklist to read their testimony to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Contemporary progressive talents, too, would be invited to reenact the Committee’s hearings. I proposed staging the event at the Writers Guild of America Theater on Oct. 27, 70 years to the day after John Howard Lawson, the Guild’s first president, became the Hollywood Ten’s first member to testify before HUAC on Oct. 27, 1947.

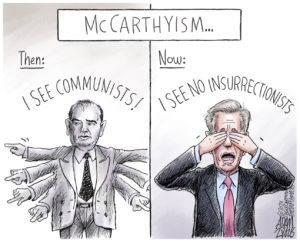

Norma enthusiastically agreed to support the endeavor. Her endorsement was essential. After all, the children of the blacklistees had been beset by the FBI, which generated lifelong suspicion. I was just a film historian with a keen interest in the witch hunt because I’d been named after legendary CBS broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, due to his televised exposes of the despotic Sen. Joe McCarthy, who carried out the Senate’s counterpart to the House’s HUAC auto-da-fé. Even though my parents hadn’t been purged filmmakers or Party members, with Norma Barzman’s imprimatur upon the commemorative project, we were able to overcome doubts, create a team, invite relatives and artists to participate and stage the HUAC reenactment and event.

In April 2023, I presented the film series “The Hollywood Ten at 75” at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures to pay homage to all of the blacklisted filmmakers.

The 70th anniversary of the Hollywood Blacklist observance lasted about four hours, featuring blacklistees’ relatives — including Mira Larkin, who read her grandfather Albert Maltz’s 70-year-old Hollywood Ten testimony — plus celebs like Richard Dreyfuss, Jamie Cromwell, Illeana Douglas, Kirk Douglas’s granddaughter Kelsey, and Turner Classic Movies host Ben Mankiewicz. Century-old actress Marsha Hunt (who, alas, died in 2022) participated, as did Norma. As she had avoided appearing before HUAC by flying the coop to live in exile in France, Norma instead read a statement she’d specially prepared for the occasion, which, along with the rest of the remembrance is online.

A few years later, I visited Norma at Beverly Hills to propose commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Blacklist. Once again, I immediately received Norma’s seal of approval. On Oct. 27, 2021, I emailed separate letters to Turner Classic Movies and the Academy informing them that exactly one year from that date would mark the 75th anniversary of the commencement of the Hollywood Ten’s testimony before HUAC, and requesting that they each recognize the start of the Blacklist. Norma’s name, but of course, was at the top of the letter co-signed by about 20 relatives of blacklistees.

Within about five minutes of receiving the email, TCM responded, thanking us for bringing this to their attention and promising to observe the Blacklist’s 75th anniversary. Sure enough, during October 2022, TCM screened vintage films by blacklistees and the original short, “High Noon on the Waterfront.” In April 2023, I presented the film series “The Hollywood Ten at 75” at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures to pay homage to all of the blacklisted filmmakers.

About a month before the series started, I phoned Norma to discuss her participation, but, very reluctantly, the 102-year-old informed me she wasn’t up to the task. She was afraid I’d be angry with her, which of course I wasn’t, although I was disappointed that the sole survivor of that American inquisition was unable to take part. And, as ever, I would miss her effervescent spirit.

I will conclude with a final, fond memory of our beloved Norma. On Nov. 27, I visited my friend, who I hadn’t seen since the pandemic started and had been collaborating with producer/writer Deborah Dobson Bach on a screen adaption of “The End of Romance,” Norma’s 2006 book largely inspired by her beloved cousin Henry. Norma was ensconced in a bed in her Beverly Hills home, cared for by a nurse. I brought a bouquet of flowers, which the nurse kindly put in a vase with water. We discussed old times and current events for more than an hour, our conversation punctuated by her mellifluous, mirthful chuckle. Norma asked me if I believed there would be a revolution someday. Before departing, I told Norma I loved her, and she called me “lovely.”

I knew it would be the last time I’d ever see my feisty friend and comrade of more than 20 years. In 1970, when Trumbo accepted a Laurel Award from the WGA, the onetime member of the Hollywood Ten described the blacklist as “a time of evil… no one on either side who survived it came through untouched by evil… [Looking] back on this time… it will do no good to search for villains or heroes or saints or devils because there were none; there were only victims.”

I respectfully disagree — all those like Dalton and Norma, who refused to cooperate with HUAC as informers in order to save their own necks, were truly heroic, whether they did it in front of the villainous Congressional committee, or from afar in exile.

A memorial service for Norma was emceed by film historian Nat Segaloff on Dec. 28, 2023, at L.A.’s Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Memorial Park and Mortuary, the final resting place for notables such as Billy Wilder, Jack Lemmon, Peter Falk and Carroll O’Connor. Inside the chapel close to 100 friends and relatives paid tribute to Norma. Paolo Barzman, Norma’s fifth child, cited a French friend who declared his mother “a heroine to many of us.” Paolo added, “She led us to believe she was immortal after all these years. ‘Die? That’s not something I do.’… She was a force de la nature,” he said in French.

John Barzman, Norma’s second child, recounted how when the Rosenbergs were executed for being “atomic spies” during the Red Scare, “the climate of fear was undeniable. It would have been easy to switch sides. But Norma remained faithful, a woman of principles.” Editor Paul Hirsch, who won an Oscar for a “Star Wars” movie, expressed the sentiments of many. “My world has changed,” he said. “Norma is gone. She has joined the legion of ghosts I carry around in my heart.” Recordings of some of Norma’s favorite songs, such as Nat King Cole’s “Nature Boy” from “The Boy with Green Hair,” were played throughout a 90-ish minute homage full of laughs and tears.On the morning of Dec. 25, Turner Classic Movies serendipitously aired the first film Norma Barzman co-wrote, “Never Say Goodbye.” Three days later, those who loved her said “goodbye” to Norma as she joined her husband Ben at the Westwood Village Memorial Park. There she lies in peace near that other Norma — Norma Jeane Mortenson, aka Marilyn Monroe — who almost 80 years earlier had warned her that the fuzz was hot on her trail.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

Thank you, Ed.

...As a child of the 50s, I recall "The Red Scare" but being young, I didn't pay much attention. I was brought up in Jamaica, NY, my father was a WWII Vet, and had mixed feelings about the Soviets. They were indeed brave, and the turning point for the war, but Stalin was a monster. I recall watching our B&W TV during the news (long before it was 24/7 rehash), Walter...

Thank you, Ed.

As a child of the 50s, I recall "The Red Scare" but being young, I didn't pay much attention. I was brought up in Jamaica, NY, my father was a WWII Vet, and had mixed feelings about the Soviets. They were indeed brave, and the turning point for the war, but Stalin was a monster. I recall watching our B&W TV during the news (long before it was 24/7 rehash), Walter...

Thank you, Ed.

As a child of the 50s, I recall "The Red Scare" but being young, I didn't pay much attention. I was brought up in Jamaica, NY, my father was a WWII Vet, and had mixed feelings about the Soviets. They were indeed brave, and the turning point for the war, but Stalin was a monster. I recall watching our B&W TV during the news (long before it was 24/7 rehash), Walter Cronkite was my favorite, but my father thought Edward R. Murrow was one of the bravest men on earth, being atop London buildings during the "Blitz".

From what I got from my dad, when Murrow called out McCarthy, he was right with him. He knew that Communists were not "under the bed" and while he disliked Stalin and Kruschev, he figured the Soviets were too spent to do anything.

To follow a story such as yours is impossible for me. I remember Marylin Monroe, Lucille Ball, et al, I think Dali was a genius. The deaths of JFK, Malcolm X, MLK, and RFK have tortured me for years; I see Norma as one of those who fought the good fight and won

I have gained a new heroine, and I thank you for the introduction.

Excellent piece. Thank you.

Thank you, Ed.

As a child of the 50s, I recall "The Red Scare" but being young, I didn't pay much attention. I was brought up in Jamaica, NY, my father was a WWII Vet, and had mixed feelings about the Soviets. They were indeed brave, and the turning point for the war, but Stalin was a monster. I recall watching our B&W TV during the news (long before it was 24/7 rehash), Walter...

Thank you, Ed.

As a child of the 50s, I recall "The Red Scare" but being young, I didn't pay much attention. I was brought up in Jamaica, NY, my father was a WWII Vet, and had mixed feelings about the Soviets. They were indeed brave, and the turning point for the war, but Stalin was a monster. I recall watching our B&W TV during the news (long before it was 24/7 rehash), Walter Cronkite was my favorite, but my father thought Edward R. Murrow was one of the bravest men on earth, being atop London buildings during the "Blitz".

From what I got from my dad, when Murrow called out McCarthy, he was right with him. He knew that Communists were not "under the bed" and while he disliked Stalin and Kruschev, he figured the Soviets were too spent to do anything.

To follow a story such as yours is impossible for me. I remember Marylin Monroe, Lucille Ball, et al, I think Dali was a genius. The deaths of JFK, Malcolm X, MLK and RFK have tortured me for years